A phage agent of change

Scientific research is defined by the scientific method: make an observation, ask a question, form a hypothesis, design and carry out experiments based on the hypothesis, analyze and report results.

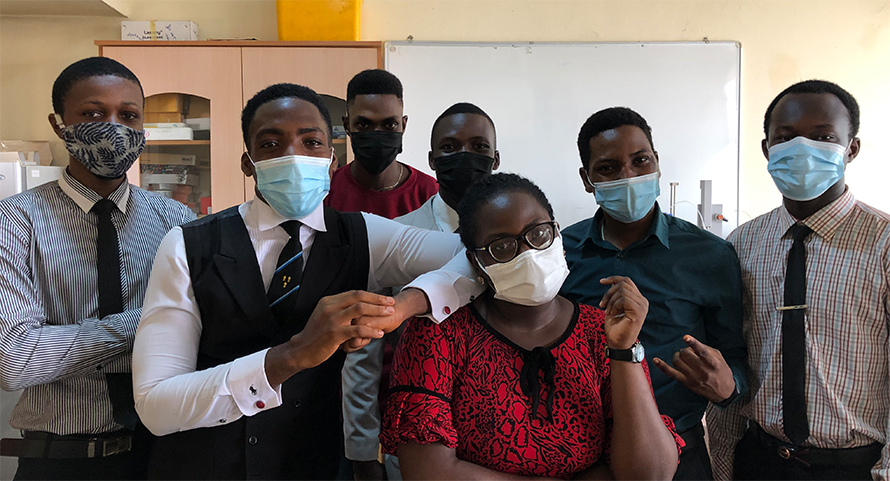

graduation from the University of Ibadan in southwestern Nigeria.

Within this central idea, a clear divide — between theory and experimentation — separates well-funded research institutions in the U.S., Europe and a number of Asian nations from institutions in Africa and South America that have a fraction, or none, of this funding. As the demand for cutting-edge research tightens its grip on funding sources, the ability of trainees at all levels to experience modern, practical research becomes restricted to countries with the strongest financial support of sciences.

Young researchers like Tolulope Oduselu now are standing up to seek reform.

Oduselu developed his love for biology and chemistry early on. “In Nigeria, when you find an inquisitive child, it’s a no-brainer for them to go into the sciences,” he said.

He opted to attend the University of Ibadan in southwestern Nigeria to study biomedical laboratory science, eager to expand both his knowledge and his practical abilities.

In his second year, Oduselu realized something was lacking. He noticed that his undergraduate courses were based heavily in theory, with little practical experience. “Many of the concepts with regard to cellular genetics or microbial genomics were not available for hands-on experimentation,” he said. “We just had to learn about concepts like the model of transcription and translation, cellular processes, and such. It was really all about theoretical knowledge — just having to pass exams.”

This weighed on Oduselu, who feels that the key to success is a strong practical course to accompany what is learned in class. “Many undergraduates just get to be a part of biomedical sciences at the theoretical level and never really get to appreciate how these concepts contribute to a broader, holistic sense of learning,” he said.

“That is one of the major limitations to biochemistry and molecular studies in Nigeria and many universities in sub-Saharan Africa.”

While students in Africa graduate with a solid foundation of knowledge, Oduselu said, their limited practical experience is “not really in tandem with the evolving scientific drive in Western countries.”

A breakthrough came for him in his third year when he reached the clinical portion of his course, structured to focus on tropical medicine and disease-causing microorganisms in the region. During this time, Oduselu was introduced to a program called SEA-PHAGES, short for Science Education Alliance–Phage Hunters Advancing Genomics and Evolutionary Science.

A bacteriophage, or simply phage, is a virus that exclusively targets bacteria. Researchers estimate that roughly 1031 types exist in the world. Their natural antibiotic tendencies make them appealing as possible therapies to tackle the ever-growing list of multidrug-resistant bacteria.

The SEA-PHAGES program, founded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, aims to turn the identification and characterization of this essentially unlimited number of novel phages into a multinational educational endeavor, with the primary goal being to improve retention of undergraduate students in the sciences, technology, engineering and mathematics.

In 2018, SEA-PHAGES’ 11th year, the University of Ibadan became the second institution in Africa to join the program. “This was the first time evolutionary sciences and genomics was really brought to the undergraduate level,” Oduselu explained, “so it was a very rough start.”

He embraced the project through its growing pains and was appointed leader of the Ibadan bacteriophage research team. “The bulk of my research experience in molecular studies and transcriptomic analysis has come from this,” Oduselu said. “It was an opportunity that is quite rare for undergraduates over here in Nigeria and in many African universities.”

Phage research in the context of antibiotic resistance is particularly relevant to Nigeria and Africa as a whole. More than half of all deaths in the World Health Organization African Region, which covers most of the continent, are caused by communicable diseases that are treated by antibiotics, according to Matshidiso Moeti, the WHO regional director for Africa.

Through his work with SEA-PHAGES, Oduselu said, he has become very aware of this. “I guess I now see myself as an agent of change, who found a very early opportunity to become aware of the problem and explore as much as possible.”

He hopes to continue his research in microbial genomics after graduation; however, he is facing a crossroad as he weighs his options of how to achieve this.

“Prior to the Ibadan Bacteriophage Research Team, very little was done on bacteriophages in Nigeria,” he said. He now is looking overseas to continue his education but said he plans to return. “It all still boils down to just learning, having the right research exposure, and bringing it back to Nigeria and Africa.”

The limitations to research in Nigeria are deep-rooted. According to UNESCO, gross expenditure on research and development in Nigeria accounts for just 0.1% of the country’s gross domestic product — just over $800,000. This is far below the recommended 1%. By comparison, the U.S. comes in at 2.7% of GDP, just shy of $500 million.

“If we do not take financial responsibility for our own research, it doesn’t matter how much international funding any African researcher can get,” Oduselu said.

of hands-on lab experience in his undergraduate classes.

This lack of internal funding is a key reason undergraduate students often miss out on hands-on practical training in biomedical sciences, he explained. And it doesn’t end there. “Many postgraduate students must pay for their own research.”

African researchers use ingenuity, collaboration and perseverance to excel despite a relative lack of resources and investment. At Ibadan, Oduselu’s mentors include George Ademowo, who works on malaria epidemiology and coordinated the framework for introduction of the malaria vaccine into Nigeria; Olubusuyi Moses Adewumi and Adeleye Solomon Bakarey, virologists researching SARS-CoV-2 in Nigeria; and Iruka Okeke, a bacterial geneticist and member of the African Academy of Sciences.

The need for funding does not stop at providing the tools for basic research, Oduselu said; African nations also need to invest in moving this research into a translational industrial pipeline. He is optimistic.

“It’s not a destination too far from now,” he said, “that scientific research in many African countries is going to meet up with the standards of what is obtainable in the Western countries.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Kiessling wins glycobiology award

She was honored by the Society for Glycobiology for her work on protein–glycan interactions.

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.

Simcox wins SACNAS mentorship award

She was recognized for her sustained excellence in mentorship and was honored at SACNAS’ 2025 National Conference.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.