Standing out and fitting in

I was halfway through my junior year of high school when I moved to the United States. When people found out that I wasn’t from here, they’d cock their heads, amused.

“But your English is perfect — you have no accent.”

I’d blush, beaming with pride, thinking, “I just got here, and they already think I belong. How about that?”

Then they’d ask me if I grew up speaking the language.

“No,” I told them, “I just watch a lot of movies and listen to a lot of songs in English. And when I do, I try to mimic how people sound.”

In retrospect, I can’t quite remember why the question about where I was from came up as often as it did.

When people asked me where I was from, I’d make them guess. I took delight in the fact that it puzzled them.

“Hmm, I’m not sure. You look mixed,” some would say.

I’m not mixed, but again I would blush, beaming with pride. Back home, my extended family admired my pale complexion, which I got from my dad. It blew their minds that my parents would let me play outside in short sleeves and risk getting darker.

“There’s no way you’re fully Asian,” they pressed, so my mom finally asked around my dad’s side of the family. That was when we found out that my dad was one-sixteenth Portuguese.

Despite that, my last name, Lius, is not related to or derived from the Spanish/Portuguese Luis. It was altered from the Chinese Liu in the 1960s when Indonesia was under an anti-Chinese regime, around the time when my parents were born. To this day, most native Indonesians and Chinese Indonesians don’t intermingle. I only have a couple of Indonesian friends that I had met in the U.S. — neither is Chinese. Although we never say it explicitly, we know that if we had met back home, we likely would have never become friends. I never felt particularly proud of either my Indonesian or Chinese identity. I never felt like I belonged back home in Indonesia. I constantly got into trouble at school because I was too liberal. Or because I asked too many questions. After I left, all I longed for was to fit in.

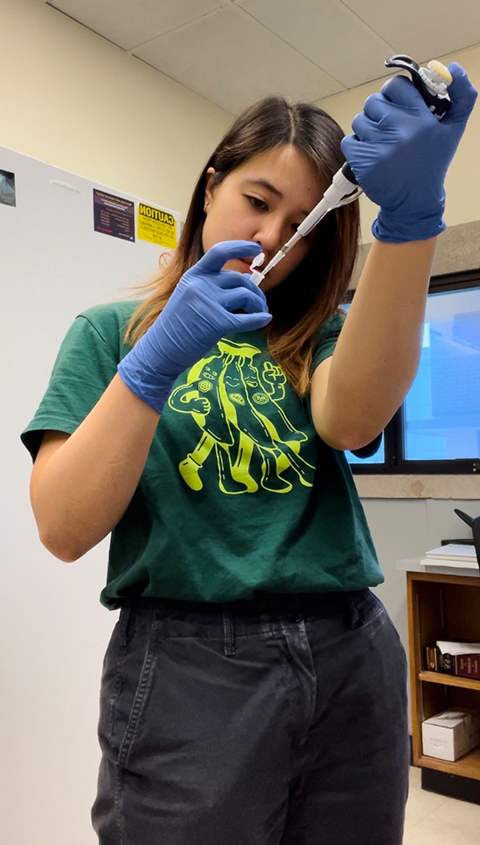

As a scientist, on the other hand, I loved being different. I wanted to stand out. I chose the only proteomics lab in my department as my thesis lab. While my peers were busy choosing their favorite protein to study, I envisioned a thesis project that mostly focused on method development.

When I was still rotating in my now thesis lab, I worked closely with a senior postdoc who was leading a project to develop a proteomics-based approach to characterize interaction partners of kinases, which are important proteins in cell signaling. As proof of concept for our method, I phenotypically characterized one of the kinases we had identified in our screen. While the kinase is quite well-known, we were the first to reveal its potential role in cancer. Moreover, my work suggested that the kinase might have functions that have not been previously characterized.

Over the next couple of years, I worked on multiple projects — a follow-up on this kinase being one of them. I always viewed the kinase project as a side project. “It’s not a method development project,” I thought. “It feels too cherry-picky for me.”Then suddenly, two weeks before my candidacy exam, my principal investigator urged me to present it as my main thesis project.

“Your committee will appreciate how far this story has developed,” he said. “You’re a second author in this paper, after all.”

As I scrambled to shift my focus to a project that I never planned to prioritize, the last thing I expected was to fall in love with it.

I learned to love cell-signaling pathways while working on my project. Over the years, this interest has taken an unexpected turn. I grew fascinated by the origins of organismal complexity. How is it that so many signaling pathways are so well conserved, yet living organisms are so diverse?

I felt inspired by scientists whose curiosities drove them to take bold interdisciplinary leaps, such as biologists who trained as physicists or medical school dropouts who found their calling in marine biology. I have always found evolution an interesting subject, but I was drawn to experimental techniques in molecular biology and biochemistry.

I recall my PI’s advice when we first met at my Ph.D. admissions interview: “Your objective as a Ph.D. student is to learn how to be an independent thinker. Choose a lab where you think you can do that best, and choose a project that excites you. There are plenty of opportunities to reinvent yourself as a scientist.”

Where does all this take my future science? Ask me again in five years. Maybe 10.

I did well on my candidacy exam, but when it was over, I struggled and often felt lost. I found myself repeating the same line at meetings and conferences: “I’m in a proteomics lab, but my project is not very proteomics focused.”

At first, I took pride in this. After all, as a scientist, I loved to stand out from the crowd. I had formulated hypotheses that pushed me well out of my (and my lab’s) comfort zone, and that takes guts. Yet, the more I said it, the lonelier I felt. I felt completely lost for some time.

When I shared my concerns with my PI, he said, “Your project is quite story-driven, which is not exactly in my wheelhouse. But it seemed that this project really grew on you, and I didn’t want to dissuade your excitement.”

I questioned whether I had made the right choice. I questioned whether I was good enough. On many days, I felt ready to throw in the towel and quit.

“We won’t let you quit. You’ve come too far,” my friends told me.

I smiled and said a little too seriously, “Well, that’s just the sunk cost fallacy.”

The fourth-year rut is apparently common, but I’d be lying if I said that the logistical limitation posed by my immigration status wasn’t a major force that stopped me from quitting. Being on a student visa meant that I had much more to lose if I decided to give it all up. So, I went through the motions, looking for a new reason each day to get me excited to go to the lab. I never cared about the title or the money, so “but I’m so close to getting my Ph.D.” wasn’t enough to get me going.

I’ve always dreamed of finding a job that I truly love. I dream of loving my job so much that I wouldn’t ever consider retiring. I dream of loving my job so much that I would (theoretically) do it for free. And, one day, I realized one pivotal thing: When I picture myself as anything other than a scientist, I feel an overwhelming sense of loss. I have never identified with anything else so strongly. I am as much a scientist as I am a Chinese Indonesian, and I love being a scientist.

“I’m ethnically Chinese,” I blurted out to my boyfriend a few months ago when we were on a road trip.

In the 10 years since I first moved to the U.S., it was the first time I’d said those words out loud. I never go out of my way to hide who I am. It’s not so hard to figure out that I’m an alien, despite the lack of an accent. I bring all my immigration documents whenever and wherever I travel, just in case. My last name isn’t printed on my passport (it’s an Indonesian thing). I can’t vote. I need a visa to travel nearly anywhere abroad.

My ethnicity, on the other hand — I never planned on volunteering that information. And yet here we are. I am a Chinese Indonesian as much as I am a scientist. Maybe someday I’ll learn to love this side of me, too.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.