Maternal diet’s effects on liver disease in offspring

More than half of people who become pregnant are overweight or obese at the time of conception, and obesity during pregnancy is associated with progeny who develop metabolic syndrome later in life.

Studies of humans and mammalian animal models have shown, for example, that high-fat diets during pregnancy and while nursing result in offspring more likely to develop nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and to have altered bile acid homeostasis.

Scientists at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis recently undertook a study to learn more about how maternal obesity might influence the development of cholestasis, a liver disease for which therapies are limited.

In cholestasis, bile cannot reach the duodenum, the first portion of the small intestine, where it is supposed to facilitate food digestion. The disease can be brought on by several factors, including duct obstructions or narrowing, toxic compounds, infection and inflammation, disturbance of intestinal microbiota, and genetic abnormalities.

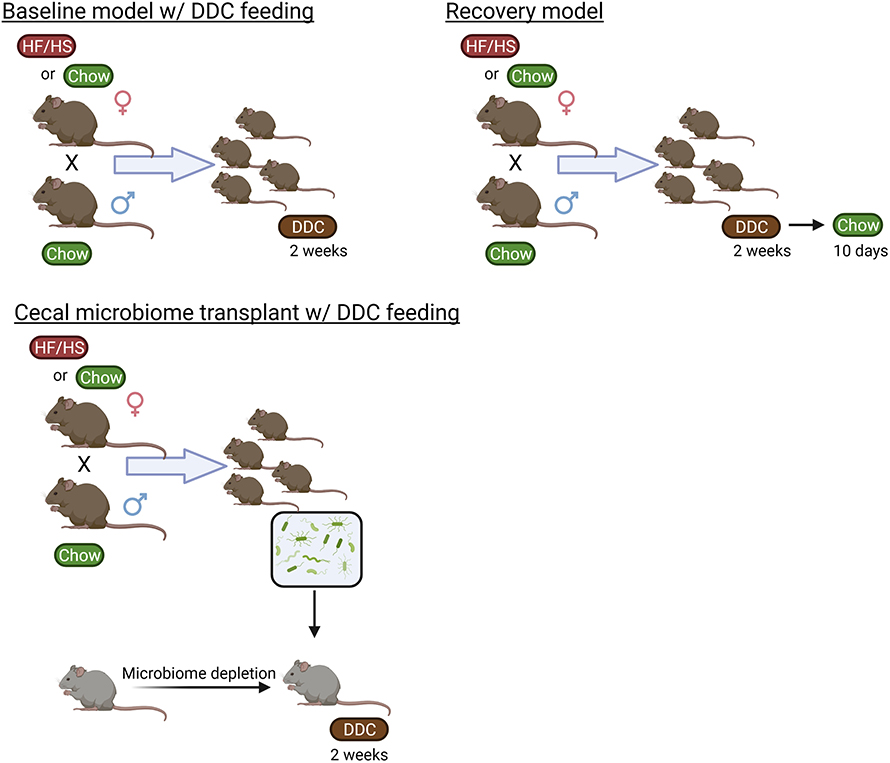

In their study, published in the Journal of Lipid Research, Michael D. Thompson and collaborators at Washington University fed female mice conventional chow or a high-fat, high-sucrose diet and bred them with lean males.

They fed the offspring DDC, which is short for 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine, for two weeks to induce cholestasis. After this feeding period, the offspring ate conventional chow for 10 more days. They found that offspring from females on the high-fat, high-sucrose diet had increased fine branching of the bile duct and enhanced fibrotic response to DDC treatment and delayed recovery times from it.

Earlier this year, the team reported changes to offspring microbiome after maternal consumption of high-fat, high-sucrose chow, so they decided to feed antibiotic-treated mice cecal contents from the offspring that had been fed conventional chow or high-fat, high-sucrose, followed by DDC for two weeks. They found that cholestatic liver injury is transmissible in these mice models, further supporting the role of the microbiome in this disease.

For those reasons and others, a lot of research has been done and continues to this day on the effects of maternal diet on offspring.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Building better tools to decipher the lipidome

Chemical engineer–turned–biophysicist Matthew Mitsche uses curiosity, coding and creativity to tackle lipid biology, uncovering PNPLA3’s role in fatty liver disease and advancing mass spectrometry tools for studying complex lipid systems.

Redefining lipid biology from droplets to ferroptosis

James Olzmann will receive the ASBMB Avanti Award in Lipids at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Life in four dimensions: When biology outpaces the brain

Nobel laureate Eric Betzig will discuss his research on information transfer in biology from proteins to organisms at the 2026 ASBMB Annual Meeting.

Fasting, fat and the molecular switches that keep us alive

Nutritional biochemist and JLR AE Sander Kersten has spent decades uncovering how the body adapts to fasting. His discoveries on lipid metabolism and gene regulation reveal how our ancient survival mechanisms may hold keys to modern metabolic health.