Tardigrades: Surviving extreme radiation

When you think about the toughest animal in the world, you might think of a lion or tiger. But a less well-known contender for this title is a tiny animal known as a tardigrade, which is renowned for surviving extreme conditions. This includes being frozen, heated past the boiling point of water, completely dried out, exposed to the vacuum of outer space, and even being bombarded with extremely high levels of ionizing radiation (Kinchin, 1994; Jönsson, 2019).

How tardigrades endure these extremes is one of the prevailing mysteries of physiology. Now, in eLife, Jean-Paul Concordet and Anne de Cian from the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle and colleagues – including Marwan Anoud, Emmanuelle Delagoutte and Quentin Helleu as joint first authors – report new insights into how tardigrades survive exposure to ionizing radiation (Anoud et al., 2024).

Ionizing radiation typically damages cells by causing their DNA to fragment (Téoule, 1987). In the past, it was thought that organisms capable of surviving extreme doses of radiation, like tardigrades, might do so by blocking and preventing the radiation from harming their DNA. A previous report suggests that tardigrades utilize a protein known as Dsup to prevent DNA damage during radiation exposure (Hashimoto et al., 2016). However, Anoud et al. found that tardigrades accumulate the same amount of DNA damage as organisms and cells which are intolerant to radiation, such as human cells grown in a dish (Mohsin Ali et al., 2004). If tardigrades do not survive ionizing radiation by directly blocking DNA damage, how do they endure such an insult?

To investigate, the team (who are based at various institutes in France and Italy) examined three species of tardigrade, using a technique known as RNA sequencing, to see which genes are switched on when exposed to ionizing radiation. They also tested tardigrades exposed to bleomycin – a drug that mimics the effects of radiation by creating double-stranded breaks in DNA.

Anoud et al. found that tardigrades upregulated the expression of genes involved in the DNA repair machinery that is common across many life forms, ranging from single-celled organisms to humans. The DNA damage the tardigrades initially accumulated following radiation or treatment with bleomycin also gradually disappeared after the exposure. Overall, these results strongly suggest that to cope with the DNA damage caused by ionizing radiation, tardigrades mount a robust set of repair mechanisms to help stitch their shattered genome back together.

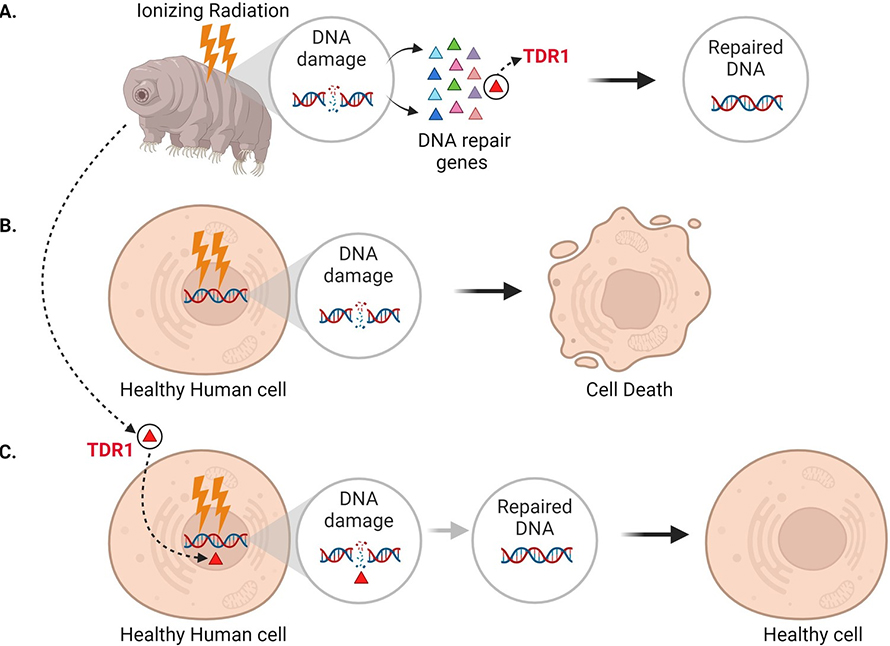

In addition to seeing that DNA repair machinery is upregulated following ionizing radiation, Anoud et al. identified a new gene only present in tardigrades, which encodes a protein they named TDR1 (short for tardigrade DNA repair protein 1). Further experiments revealed that TDR1 can enter the cell nucleus and bind to DNA. This may be due to conserved portions of TDR1, which are largely positively charged, electrostatically interacting with negatively charged DNA. Moreover, at high concentrations, TDR1 not only binds to DNA, but forms aggregates in a concentration-dependent manner. Finally, Anoud et al. found that introducing the gene for TDR1 into healthy human cells reduced the amount of DNA damage caused by bleomycin, indicating that the TDR1 protein helps with DNA repair (Figure 1).

Expressing the tardigrade protein TDR1 in human cells increases DNA damage repair.

While it is still unclear exactly how tardigrades fix DNA damage, this study suggests that their ability to survive extreme radiation is related to their strong DNA repair ability, which TDR1 likely plays a crucial role in. Anoud et al. found that TDR1 did not accumulate at DNA damage sites like some other repair proteins (Rothkamm et al., 2015). Instead, they propose that the protein mends DNA by binding to it and forming aggregates which compact the fragmented DNA and help maintain the organization of the damaged genome.

However, more research is needed to fully understand the mechanism responsible for TDR1 and other proteins helping tardigrades to survive ionizing radiation. Ultimately, knowing how these tiny organisms efficiently repair their DNA could lead to novel strategies for protecting human cells from radiation damage, which could benefit cancer treatment and space exploration.

This article is republished from eLife. Read the original here.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.