Pivoting from carnivorous plants to COVID-19

You might not think that research into how carnivorous plants digest their meals would be remotely useful in responding to a pandemic. But that’s the thing about basic research: Its applications are unpredictable.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Rachel Martin, a biophysical chemist at the University of California, Irvine, studied diverse proteases, including from the carnivorous sundew plant, for a different purpose, to explore ways to break down harmful, protease-resistant aggregates such as amyloid plaques.

Now, Martin is leading many of the labs in her department in a research consortium that aims to design new protease inhibitors specific for the coronavirus protease. Working six feet apart in the lab or from home using software for virtual screens, the team hopes to contribute to a future arsenal of antivirals against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

A hunt for protease inhibitors

Proteases play an important role in COVID-19 infection. The novel coronavirus translates much of its RNA genome into two long polyproteins. It requires a protease called MPro, or the main protease, to cleave that long polyprotein into 16 individual active units that replicate the viral genome, hijack the host cell’s immune response and carry out other nonstructural roles.

Protease inhibitors have been successful treatments for other viral infections, such as HIV. Drug repurposing studies such as the World Health Organization’s Solidarity Trial are testing the HIV protease inhibitors ritonavir and lopinavir in patients with COVID-19 to see whether they give clinical benefit.

But existing drugs developed for other viral proteases may fail to block Mpro. Even if they do work, there’s a possibility that their effect will be limited or that widespread use will promote viral resistance. In all likelihood, cocktails of multiple antivirals will be needed, so scientists around the world are racing to find compounds that inhibit MPro activity and might become, or inspire, future drugs.

That’s where Martin, vice chair of the chemistry department at UCI, comes in: A protease expert whose lab is conversant in both computational and biochemical studies, she saw an opportunity to contribute to the hunt for protease inhibitors.

Proteases from carnivorous plants

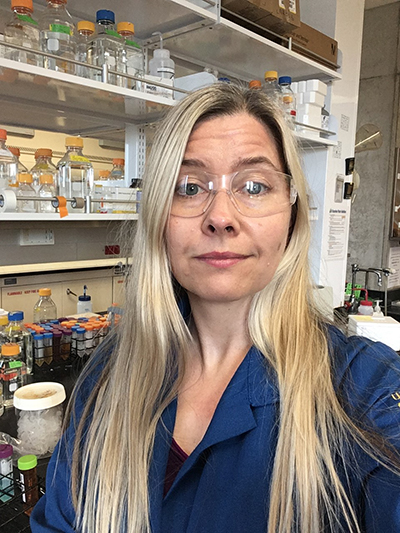

place to look,” said UCI professor Rachel Martin, who has applied her lab’s

expertise in cysteine proteases from sundew plants (pictured) to study the

cysteine protease of SARS-CoV-2.

Martin studies the biophysics of protein aggregation, which is linked to human diseases such as Alzheimer’s. One possible strategy to reverse harmful aggregation would be to introduce new proteases. To find proteases with new functions, Martin and colleague Carter Butts sequenced the genome of the sundew Drosera capensis, a plant that traps and slowly digests insects that land on its sticky hairs.

“If you want to find interesting enzymes, a carnivorous plant is a really good place to look,” Martin said. Unlike animals, which break down food mechanically and digest it in specialized organs, she said, a carnivorous plant “has to perform all of its digestive functions right out in the open, where it’s in competition with bacteria and fungus. … All it has are really amazing enzymes.”

Once Martin and her team identified 44 new cysteine proteases in the sundew genome, they needed to predict each protease’s substrate selectivity to decide where to focus their biochemical resources.

After using a program called Rosetta to predict the structure of each protease and refining those predictions manually, the team used molecular docking simulations and machine learning to predict the substrates each enzyme might be able to bind and cleave.

When COVID-19 struck, Martin said, she realized that the pipeline her team used to search for substrates could be converted to seek inhibitors instead. After all, she said, “If you think about it, an inhibitor is just a substrate that doesn’t do the chemistry.”

Martin knew her lab could contribute. As most of the UCI campus prepared to shut down, she prepared her team to launch a socially distanced research project. James Nowick, a chemistry professor in a neighboring lab, was ticking through a shutdown checklist when Martin stopped in to ask that he leave the shared ultrapure water system on—she was going to need it. Nowick said, “It was like a lightbulb went on — that biomedical scientists should be putting all hands on deck to solve this problem.”

He wasn’t the only fellow professor to sign up to help; the consortium quickly grew to ten labs. Martin said, “Basically every colleague that I told about it said, ‘What can I do?’”

An assay for robust inhibition

The consortium includes two computational labs and six experimental labs in addition to Martin’s from the UCI chemistry department. The team has two research goals; the first is to find one or more inhibitors that specifically inhibit the SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

Much like the sundew protease project, the work starts with computational modeling. The team takes a structure — the European protein database currently lists 124 reports on the structure of the protease, including many in complex with ligands — and uses molecular simulations to predict other possible conformations. Then, they dock ligands numbering in the thousands from libraries curated by DrugBank, UC Irvine and other academic institutions around the world to see which are best able to bind to the enzyme’s active site. This lets them narrow down the dizzying list of potential molecules to strong candidates to be tested in the wet lab.

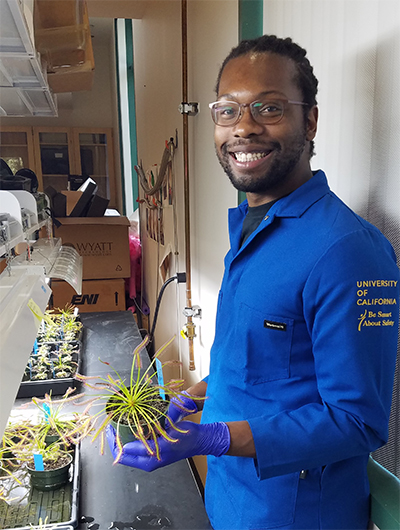

sundew to producing protease.

To test how well the modeled chemicals work in a test tube, the consortium needs huge quantities of purified protease, which Martin’s lab is producing and characterizing, and adequate amounts of each of the promising compounds, which the department’s synthetic labs are producing. They also need to monitor how active the protease is in the presence of each candidate inhibitor. Researchers in Nowick’s lab synthesized a probe that had been published, but was not yet available for sale. When the protease cleaves the probe, it fluoresces, allowing high-throughput testing of candidate inhibitors in a 96-well plate format.

Mapping mutational landscapes

The consortium is pursuing a second goal in tandem with the first: to identify inhibitors or combinations that make it difficult for the virus to develop resistance.

The team has started by working to understand what Martin calls the mutational landscape of the protease in circulating coronavirus strains. If there is already a strain in circulation that can resist a candidate protease inhibitor, that’s crucial information for moving forward. Similarly, if resistance is just a mutation or two away, the scientists would like to know that.

Every day, undergraduate T.J. Cross, who joined Martin’s lab just days before the university shut down, and graduate student Gemma Takahashi comb an epidemiological sequencing database in search of new mutations to the protease. Each time a laboratory submits a sequence to the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data, or GISAID, that includes a new protease mutation, the team uses molecular dynamics simulations to model how it affects the protein’s shape, movements and interaction with selected compounds. In May, the team posted a preprint analyzing 79 known variants of the protease.

“Right now, we are simulating every single one,” Martin said. “And yes, it is expensive. Yes, we’re doing it. We know that it may not be sustainable long term … but we’re going to do the best we can for a while.”

Logistics of a big consortium

Martin’s salary, those of her faculty colleagues and their students and postdocs, are funded by grants, and she said that program officers have been happy to support their pivot to COVID-19 research. Covering the cost of reagents and computer time has been more of a challenge. The university has dedicated some discretionary funding and led crowdfunding efforts to support the project, but to keep it going long-term, the group will need more funding. That’s a challenge, as grant cycles move much more slowly than this project has.

Martin has led research consortia before, but never one that came together so fast. Within eight weeks of conceiving of the project, she was supervising the first positive control assays remotely. Soon, she said, the team hopes to test its first candidate compounds.

At the same time, she added, because just two people can safely work in the lab at a time, the work seems to move achingly slowly. Every stint at the bench must be carefully coordinated in the lab’s Slack channel. Members of the lab also miss sharing ideas, technical advice and the simple pleasure of each other’s company.

“The stereotype of a lab scientist is somebody who’s socially maladjusted and has no friends, but that’s not how it works at all,” Martin told the audience of a recent webinar. “Experimentalists are very social!”

Martin has also stayed in close contact with other teams working on protease inhibitor development. Around the world, teams at the University of Hamburg, the University of Science and Technology of China, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, and the University of California, San Francisco, and other international consortia are working to develop protease inhibitors.

“We’re keeping in touch to make sure that we’re not duplicating efforts,” Martin said. “Everybody I’ve talked to from all over the world … has been very collaborative and eager to solve the problem.”Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.