How does a baby 'breathe' while inside its mom?

“Mothering” is synonymous with “nurturing,” probably because moms start providing for their kids even before they’re born.

A fetus relies on its mother to provide all the essentials. The placenta is key here; this organ develops in the uterus and is like a gateway that lets mom pass baby everything it needs to support its development.

After the mother eats, her body breaks the food down into glucose, amino acids, fatty acids and cholesterol that travel through channels or transporters in the placenta to the fetus. They provide the energy and the building blocks that the growing fetus uses as it develops organs, tissues and bones.

Vital electrolytes like sodium, chloride, calcium and iron pass through their own specific channels in the placenta or just diffuse from the mother’s side to the fetus’s.

Fetuses require oxygen for growth, too. Since their lungs are not exposed to air, they can’t breathe on their own. Instead they rely on their mothers to provide the required oxygen through a remarkable biochemical process.

I’m a biochemist, and it’s this process that made me fall in love with the discipline when I was a student. It’s my favorite topic to present to my students today and helps explain why pregnant women can get so easily winded.

Oxygen running through your veins

Some ingenious biochemistry is at the root of how oxygen travels throughout the human body.

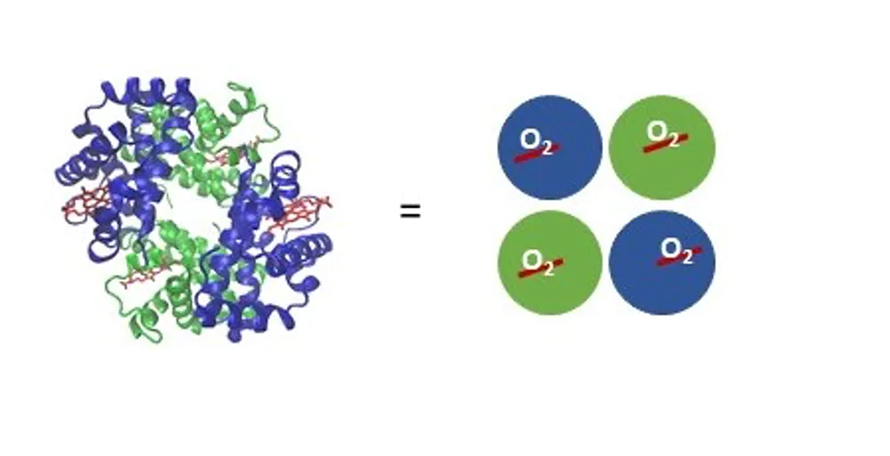

A protein called hemoglobin is responsible for picking up oxygen in your lungs and carrying it via your bloodstream to all of your tissues. Hemoglobin contains iron, and it’s responsible for blood’s red color. It’s made up of four subunits, two each of two different types.

Each subunit contains one iron atom bound to a special compound called a heme that can interact with one oxygen molecule. It’s an all-or-nothing situation; for hemoglobins in the same vicinity, they’re either all holding onto oxygen or have all released their oxygen. It depends on the concentration of oxygen in the environment the hemoglobin finds itself in.

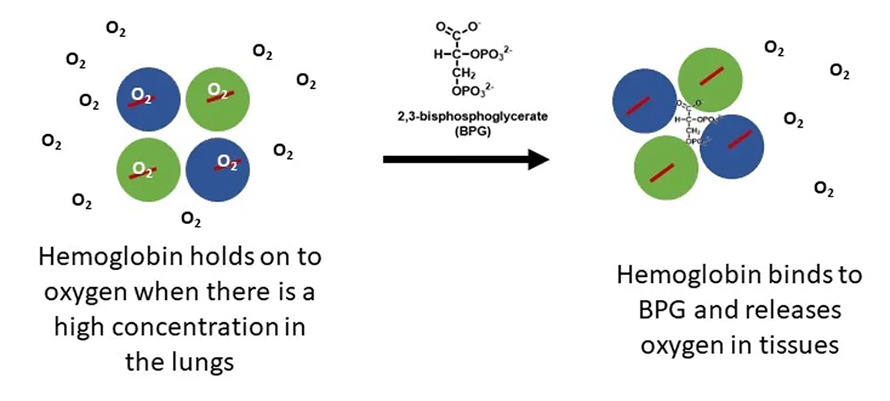

When you take a good breath, the concentration of oxygen is high in your lungs. Hemoglobin in the area automatically picks up oxygen. Then it travels via your blood to tissues with lower oxygen concentrations, where it gives up the oxygen.

A molecule called 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate, or BPG, facilitates oxygen’s release. It binds to the center cavity between the four subunits of hemoglobin to help the oxygen molecules pop free.

Getting oxygen to the fetus

Fetuses are not exposed to air, and their lungs don’t fully develop until after they’re born, so oxygen is another on the long list of things they must get through the placenta from their mothers.

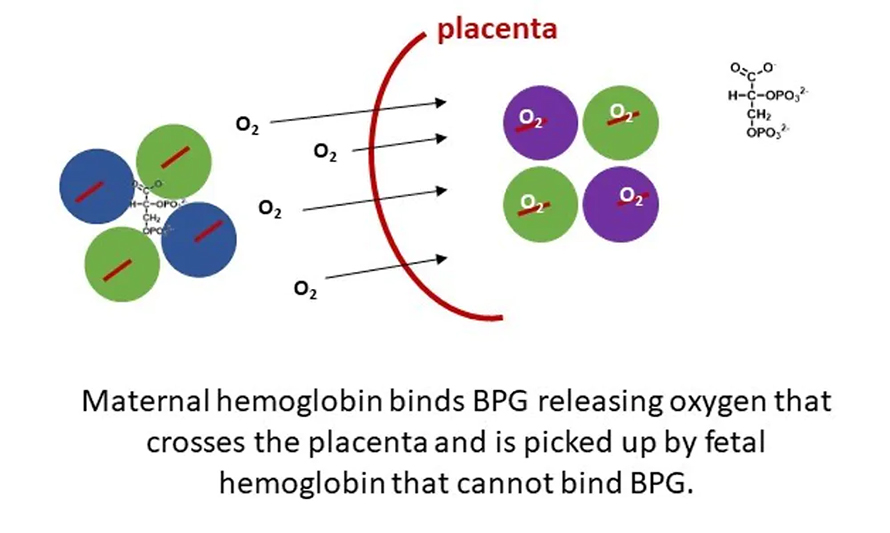

Hemoglobin proteins are too big to cross the placenta. The maternal hemoglobins must give up their oxygen molecules on their side so the oxygen can cross over and be picked up by the fetal hemoglobins on the other side. The predicament is that since this is all happening in such close quarters, the hemoglobins should either all be holding on to oxygen or all be releasing it.

In order to circumvent this problem, fetal hemoglobin differs in structure from maternal hemoglobin. With just a few changes to the amino acids in its protein sequence, fetal hemoglobin does not bind well to BPG, the molecule that helps oxygen get loose from adult hemoglobin. Fetal hemoglobin also has a stronger affinity for oxygen than the adult version does.

So at the placental interface, where there’s a lot of BPG, the maternal hemoglobin lets go of the oxygen and the fetal hemoglobin grabs ahold of it tightly. This process allows for effective and efficient transfer of oxygen from the mother to the fetus.

Shortly before babies are born, they start making some adult hemoglobin so that when they are breathing on their own, they can perform appropriate oxygen transfer throughout their little bodies. Usually by the time a baby reaches six months of age, the levels of fetal hemoglobin are very low, replaced almost completely by adult hemoglobin.

Academically, I knew about this remarkable biochemical process. But it wasn’t until I was pregnant with my son that I really understood it. My miles in spinning class decreased, I lagged behind my husband and dog on our daily walks, and I ran out of breath climbing the three flights of stairs to my office. My son’s hemoglobin was stealing my oxygen, so I had to breathe in more to complete routine tasks.

Once my baby was on the outside, breathing on his own with his mature hemoglobin functioning appropriately, I was more amazed than ever at the perfection of the science.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Missing lipid shrinks heart and lowers exercise capacity

Researchers uncovered the essential role of PLAAT1 in maintaining heart cardiolipin, mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, linking this enzyme to exercise capacity and potential cardiovascular disease pathways.