Scrutinizing the greatest threat to pigs

African swine fever virus is harmless to humans, but pigs aren’t so lucky. The virus, endemic to warthogs, bushpigs and soft ticks in sub-Saharan Africa, causes a hemorrhagic fever in domestic swine.

D. CHARRO, G. ANDRÉS, N.G. ABRESCIA

Since making its way to the Republic of Georgia in 2007 via the pork trade, a strain of the virus has swept through China and much of Southeast Asia, killing hundreds of thousands of pigs directly and nearly 200 million more by culling. Although a number of promising vaccine candidates are being developed, they still face hurdles and only protect against the appropriately named Georgia 2007 strain, while many equally deadly strains circulate in Africa.

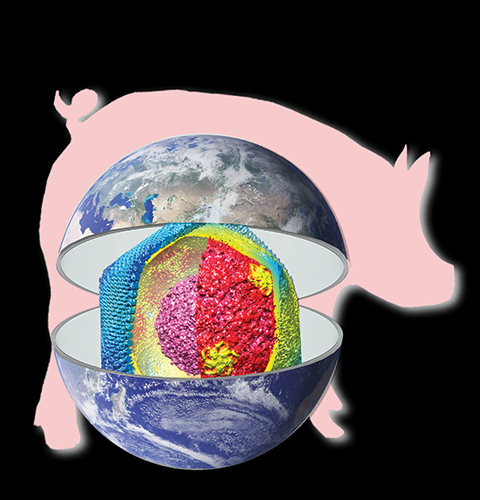

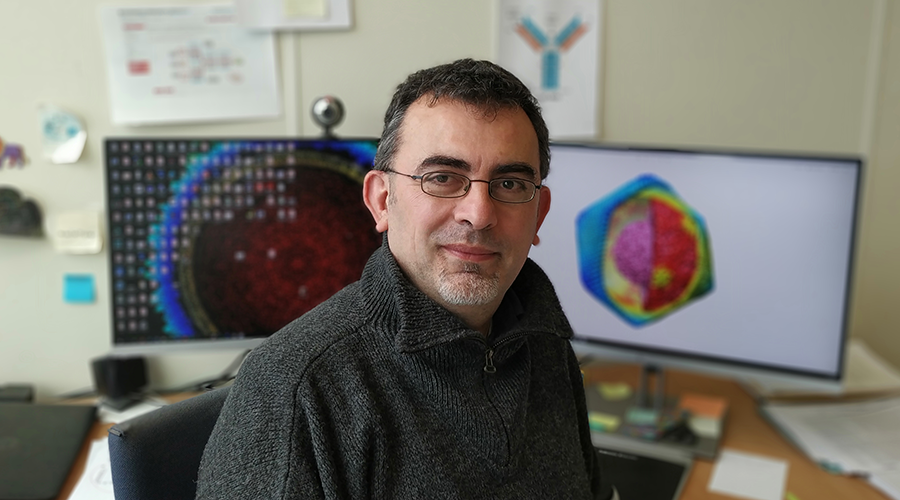

The virus’ unique multilayered architecture may be blocking vaccine development. Nicola G. A. Abrescia, German Andrés and their colleagues recently peered between those membranes to capture the structure of ASFV’s virion. They described its architecture in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

“What was striking is that actually you have four layers: two envelopes and two protein capsids for this virus,” said Abrescia, a structural biologist at the Center for Cooperative Research in Biosciences near Bilbao, Spain. “So you have this outer envelope which is acquired when the virus goes out of a cell, but below this envelope you have another set of icosahedral capsids and in between a membrane bilayer, all of them enclosing the genome-containing nucleoid.”

In previous studies, Andrés found that both the extracellular and intracellular forms of ASFV are infectious, which suggested that the outer membrane might not be necessary for infectivity, as the virus sheds its coat while entering into a host cell. The researchers hope that a better understanding of ASFV’s structure might contribute to more efficient vaccine design.

Abrescia, who examines how the structure and assembly of viruses with complex membranes affect pathogenicity, began collaborating with Andrés after becoming intrigued by ASFV’s unique double lipoprotein membranes and outer capsid protein fold. Andrés, a senior researcher at the Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa’s Electron Microscopy Unit in Madrid, set his sights on the virus while working on his doctoral thesis in the early 1990s during the height of the Spanish government’s efforts to rid the Iberian Peninsula of African swine fever.

Long before Georgia 2007 appeared, another strain of ASFV arrived in Portugal in 1957. From Lisbon, the virus crept across the country and reached Spain in 1960; it leaped across that country as pigs were shuffled between recently industrialized farms. With the aid of the soft tick Ornithodoros erraticus, the virus became entrenched in Spain’s population of wild boars, which mingle often with domestic pigs. For the next two decades, African swine fever flared up in Western Europe, the Caribbean and Brazil. By 1985, pork producers and the Spanish government had had enough and embarked on a successful 10-year campaign of sanitation, detection and eradication. Andrés has been probing ASFV’s structure and assembly pathway ever since.

One challenge of working with ASFV is the virus’ size. ASFV is big — a giant virus, in fact, almost twice the size of influenza virions and thicker than the typical layer of ice in which particles are suspended for cryo-electron microscopy. This complicates sample preparation. Additionally, most microscopes’ field of view can capture only a few virus particles, challenging efficient data collection. And despite its size, ASFV’s outer membrane isn’t resilient outside of a host.

“The outer lipid envelope is relatively fragile,” Abrescia said, “so you have to set up a very good purification protocol which doesn’t destroy so much of the virus’s envelope.”

Once the researchers had optimized their protocol, they went to co-author Rebecca Dillard’s lab at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands to use the institution’s Titan/Krios transmission electron microscope, collecting cryo-images of a thousand viral particles. The virus’ size also causes its capsids to span more than one focal plane, contributing to image blur. To tackle this, Abrescia and Andrés biochemically deconstructed the virus in solution and then purified and resolved the fold of the individual protein composing the outer capsid.

Abrescia’s team isn’t alone in pursuing the structure of ASFV. A few days before their JBC paper appeared online in October, a group at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing described the pathogen’s structure at greater resolution in the journal Science, and in late November, a third group at the University of Science and Technology of China published another cryo-EM analysis of ASFV in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

But despite the success of these groups, and a fourth group who described the structure of ASFV’s major capsid protein p72 in the journal Cell Research in September, the inner capsid remains a challenge.

“Even the high-resolution structures that our Chinese colleagues have obtained do not fully explain the inner capsid,” Abrescia said. “Indeed, it has remained something that requires more exploration.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.