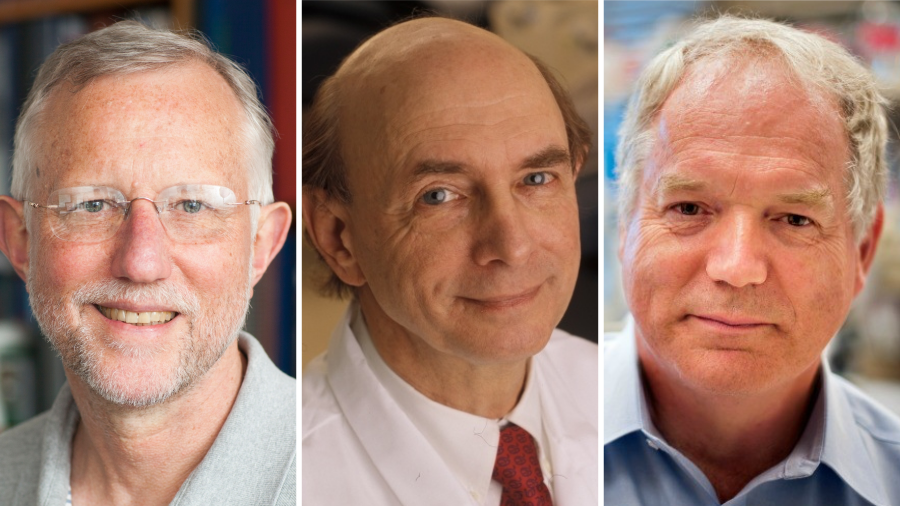

Charles M. Rice shares the Nobel for hepatitis C research

Charles M. Rice at The Rockefeller University, Harvey J. Alter at the National Institutes of Health and Michael Houghton at the University of Alberta have won the 2020 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for the discovery of the hepatitis C virus.

While overconsumption of alcohol, environmental toxins and autoimmune disease play significant roles in global incidence of liver inflammation, or hepatitis, viral infections cause the majority of cases. Hepatitis A, B, C and E viruses all cause liver inflammation, but the viruses are only distantly related.

Hepatitis A and E are transmitted by contaminated food or water and cause acute disease. Hepatitis B and C, as well as hepatitis D, which can propagate only in the presence of hepatitis B, are chronic blood-borne pathogens that spread through intravenous drug use and blood transfusions. Together, blood-borne hepatitis viruses, which result in cirrhosis and liver cancer, cause more than 1 million deaths each year.

In the 1960s, physician Baruch “Barry” Blumberg discovered hepatitis B, which led to the development of diagnostics and a vaccine for the virus. In 1976, Blumberg, along with D. Carleton Gajdusek, won the Nobel for physiology or medicine for their work on the virus. (Blumberg’s birthday, July 28, was adopted as World Hepatitis Day.)

In the early 1970s, Alter, a physician at the National Institutes of Health, investigated hepatitis in patients who had received blood transfusions but had tested negative for the A and B viruses. The new illness, then known as “non-A, non-B” hepatitis, became a priority for Michael Houghton, who was working for the pharmaceutical firm Chiron. In 1989, he and his colleagues isolated the genetic sequence of the virus. However, they encountered difficulties getting the new virus to replicate in the lab.

That final piece of the infective puzzle was ultimately solved by Rice, a member of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, who was then conducting research at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Rice engineered a variant of the virus that was devoid of genetic segments that might be inactivating a region of the virus they suspected was involved in replication. When this variant was injected into the liver of chimpanzees, it caused changes in blood and pathology resembling those seen in humans with the mystery hepatitis, providing direct evidence that the hepatitis C virus was responsible for the transfusion-mediated hepatitis.

The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, which administers the prize, noted in a press release that “thanks to their discovery, highly sensitive blood tests for the virus are now available and these have essentially eliminated post-transfusion hepatitis in many parts of the world, greatly improving global health.”

The researchers’ work also enabled the development of the antivirals pegylated interferon and ribavirin, which help the body rid itself of hepatitis C.

“For the first time in history, the disease can now be cured, raising hopes of eradicating hepatitis C virus from the world population,” the Nobel Assembly wrote.

Rice, a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences and a member of the National Academy of Sciences, earned his bachelor’s degree in zoology from the University of California, Davis, in 1974. He then earned his Ph.D. at the California Institute of Technology in 1981, where he subsequently performed postdoctoral research from 1981 to 1985.

Rice established his research group at WUSTL in 1986, became a full professor in 1995, and moved to The Rockefeller University in New York in 2001.

He, Alter and Houghton will each receive one-third of the roughly $1.1 million prize.

“For many years, it was impossible to get the hepatitis C virus to replicate in liver cells in the laboratory,” said Michael W. Young, also an ASBMB member, who won the Nobel Prize in medicine or physiology in 2017 for discovering the molecular mechanisms that control circadian rhythms. “Charlie Rice discovered a feature of the viral genome that could be changed to permit replication in isolated cells. This allowed the development of potent drugs that blocked growth of the virus in the lab and subsequently in infected patients. It was a stunning victory for medical science.”

Gregory Petsko at Harvard Medical School and Brigham & Women’s Hospital, a former ASBMB president, noted the timing of the prize is simultaneously fitting and overdue.

"At a time when a virus has upended the whole world, it seems appropriate for the Nobel to be awarded to a team of virologists," Petsko said. "It was Alter at NIH who first showed that a virus caused the deadly liver disease hepatitis C. Houghton then sequenced the genome of this seemingly unculturable agent. And our own Charles Rice did the experiment to satisfy the last of Koch’s postulates when he showed the virus could actually cause the disease it was thought to cause."

He continued: "When the Nobel committee makes its announcements, there are a lot of reactions one can have. In this case, my reaction was, 'What took them so long?'"

The basics of hepatitis

ASBMB Today contributor Michael Pokrass wrote in July about the history and clinical effects of hepatitis. Read his health observance article, which includes summaries of recent hepatitis research published in ASBMB journals. Our World Hepatitis Day 2018 article includes even more research highlights.

In 2010, the Journal of Biological Chemistry published a thematic minireview series showcasing advances in hepatitis C research. Then-Associate Editor Charles Samuel, who organized the series, noted that two of the authors later shared the Lasker prize for their hepatitis C work. Read the reviews here.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Kiessling wins glycobiology award

She was honored by the Society for Glycobiology for her work on protein–glycan interactions.

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.

Simcox wins SACNAS mentorship award

She was recognized for her sustained excellence in mentorship and was honored at SACNAS’ 2025 National Conference.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.