Meet Mona Nemer

Mona Nemer was appointed Canada’s chief science adviser by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in the fall of 2017. For the past year, she has been responsible for counseling Trudeau and his cabinet, in particular the science minister, Kirsty Duncan, on pressing scientific matters. She also is tasked with fostering collaboration among scientists in academia and government and serving as a champion of science in the public sphere.

Like many members of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Nemer, a heart researcher, spent most of her career in academic science. She earned her Ph.D. in bio-organic chemistry at McGill University, worked in industry, became a faculty member and later administrator at the University of Montreal, and then moved to the University of Ottawa, where she was a professor, director of the university’s Molecular Genetics and Cardiac Regeneration Laboratory, and, for 11 years, vice president for research.

The last time Canada had a national science adviser was about a decade ago.

Prime Minister Paul Martin of the Liberal Party appointed the first in 2004. His electoral successor, Stephen Harper of the Conservative Party, eliminated the position, along with the top technology adviser spot, in 2008 shortly after his government established the Science, Technology and Innovation Council.

Given that the newly formed council had less public visibility, critics saw the office closures as part of the Harper government’s broader effort to sideline science and muzzle scientists.

When Trudeau ran as the Liberal Party candidate in 2015, he made the appointment of a chief science adviser part of his platform. He and his party won, and Nemer’s appointment fulfilled that campaign promise.

Nemer grew up in Lebanon, the eldest of three children born to a schoolteacher and a mechanic for Beirut newspapers. She attended an all-girls high school. At that time, the mid-1970s, the school didn’t have a science track, so Nemer and her peers began a campaign to get one. “We had a sort of mini-revolt,” she told the Toronto Star last year. The effort was successful, and Nemer was one of 17 students admitted to the new program.

Already fluent in Arabic and French, Nemer worked on her English while at a Beirut university for more than a year. She then transferred to Wichita State University in Kansas, where she had relatives.

Canadian Prime Minster Justin Trudeau (left) made appointing a chief science adviser part of his campaign platform in 2015. When he and the Liberal Party won election, Mona Nemer applied for the job. She was appointed in 2017.All Photos courtesy of Mona Nemer’s OfficeThe move was a culture shock. Beirut had been a bustling, multilingual and multicultural metropolitan. Wichita was not. Nevertheless, she persisted.

Canadian Prime Minster Justin Trudeau (left) made appointing a chief science adviser part of his campaign platform in 2015. When he and the Liberal Party won election, Mona Nemer applied for the job. She was appointed in 2017.All Photos courtesy of Mona Nemer’s OfficeThe move was a culture shock. Beirut had been a bustling, multilingual and multicultural metropolitan. Wichita was not. Nevertheless, she persisted.

Come graduation time, Nemer had a scholarship offer from a Ph.D. program at the University of Michigan. But a quick trip with friends to Montreal scuttled those plans.

Attracted by the offerings of city life, Nemer decided to pass on Michigan and instead go to McGill, where she later did postdoctoral work as well.

ASBMB Today’s executive editor, Angela Hopp, and the ASBMB’s policy analyst, André Porter, talked to Nemer about her experiences on the job over the past year, what students and researchers should know about doing science in Canada, the role of scientists in policy-making, and how to make science more inclusive for women and underrepresented minorities. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Could you talk a bit about what is expected of you on a day-to-day basis?

It’s very varied, and that’s what makes this job exciting. It goes from meetings with the senior bureaucrats or ministers to discuss specific programs or scientific activities within their department and ministries, to meeting various stakeholders from the Association of Physicists, to having conversations both within government and with outside people on the best way forward on certain major themes or initiatives — say like artificial intelligence and its applications to various fields — to how we would go about having a national strategy for personalized medicine or Arctic research. It’s different activities — from science literacy and science promotion to visiting major infrastructure, both nationally and internationally, to representing Canada on different panels.

Do you think that there are any misconceptions about the purpose of your role or what you do?

I think, by and large, the (Canadian) public understands the importance of evidence-based decision-making. The reception of my appointment was way beyond expectations.

In terms of the scientific community, their expectation is that I’ll serve as a bridge between the extramural science community and government, perhaps enhance understanding of what the research activity and the science are about — how the enterprise functions — clearly with the expectation that there will be enhanced recognition and support for research. Before becoming Canada’s chief science adviser, Mona Nemer served as the University of Ottawa’s vice president for research and as a professor of biochemistry. Her lab focused on the molecular pathways underlying cardiac cell growth and differentiation.

Before becoming Canada’s chief science adviser, Mona Nemer served as the University of Ottawa’s vice president for research and as a professor of biochemistry. Her lab focused on the molecular pathways underlying cardiac cell growth and differentiation.

You’ve been in it for almost a year now. How is the reality different from your expectations?

The reality is that the position that I have — and that exists in many places around the world — is really much needed. It’s not just political posturing. It’s interesting to have someone who’s not in a ministry or a specific department taking a look and trying to convene people from all these stakeholder sectors and disciplines.

The reality is that government actually moves really slowly. This may not be the discovery of the century, but it’s sort of even slower than I thought. I thought universities were slow and you needed to do multiple consultations and so on. Some days, I think, “Well, maybe it’s, in a way, a safeguard. It may take the ship a long time to turn, but it will also take it a long time to sink.” Maybe it’s a sort of guarantee of some stability for our democracy. But I just wish that we could do things a bit faster.

Prime Minister Harper was known for having cut funding for certain types of research. Trudeau appears to be trying to reverse that seemingly negative view or skepticism of science. What impediments are there to improving perceptions?

If I compare Canada with countries with a longer history, for example in Europe, I would say that the scientist in Canada has been generally less involved in public policy and interactions with politicians and with the public in general. I think it’s fair to say that most of the interactions between scientists and elected officials have been around asking for more funding, so then they’re viewed (by elected officials) as just basically another interest group.

But the bigger picture is that, because of this dynamic, science literacy and the appreciation of science and of research more generally in Canada lag behind countries like France and Germany and the U.K. It used to be that the public cared about typical scientific issues around health. But increasingly in the past several years, the public has shown greater interest in environmental issues, about food safety, about water safety, in addition to health of course, and then things like data security.

We have had here a sort of conundrum. On the one hand, the population wants to learn more; on the other, we haven’t had intense or even appropriate engagement by scientists, whether they are within or outside government.

I guess the tipping point came when the public started hearing that, basically, scientists were being muzzled and started to worry whether legislation was being conducted with evidence or simply based on ideology.

The ground there is very fertile for scientists to engage with the public and for the public to be receptive.

One of the things that we’re concerned with in the U.S. is rhetoric deterring international talent.

The U.S. is the perfect example of how a nation has prospered because they were able to attract the best scientists and engineers from across the globe. U.S. dominance in terms of science started after World War II. I think there is a pretty interesting link with all the folks who fled Europe and other places in the world since then and came over to the United States. The U.S. is the perfect example of what science internationalization and openness to the world has actually done in terms of positive impact on the country itself. It’s a little bit surprising when governments talk about restricting international collaboration, because, historically, researchers have collaborated across borders. Women with STEM backgrounds are front and center in the Canadian government. Kirsty Duncan (left), a medical geographer, is the country’s science minister. Mona Nemer (right), an expert in the molecular mechanisms of the heart, is the chief science adviser. Julie Payette, who served as the chief astronaut for the Canadian Space Agency, is the governor general.

Women with STEM backgrounds are front and center in the Canadian government. Kirsty Duncan (left), a medical geographer, is the country’s science minister. Mona Nemer (right), an expert in the molecular mechanisms of the heart, is the chief science adviser. Julie Payette, who served as the chief astronaut for the Canadian Space Agency, is the governor general.

People in the U.S. often say that they will move to Canada if some sort of terrible political thing happens. But in all seriousness, can you talk about what Canada has to offer students and researchers?

First of all, we have the same North American educational system. If you’re in Europe or the Far East or the Middle East and you want a North American-type education and networking and exposure, Canada certainly can offer as good an environment as the U.S.

Canada generally is viewed as a more welcoming society. Canada is viewed as perhaps more multicultural than other countries and also has less tension between the different cultures.

In the past year, Canada has taken some serious steps in terms of immigration. There are, for example, much shortened or accelerated visa programs and other immigration changes for students, for researchers being hired at Canadian universities or in the private sector. In fact, some of the tech companies from the States have opened branches in Canada — both on the west coast, in Vancouver, and in Toronto — because they find it easier actually to recruit talent from across the globe to Canada, where there are more simplified immigration procedures than for the U.S.

Canada has also put in place many programs to attract disgruntled researchers or researchers who are feeling destabilized by geopolitical conditions. Of course, it’s not only in the Americas, but it’s also in Europe with Brexit and some other European countries where the economic situation is not as good.

You have, for example, the Canada 150 Research Chairs program that was announced and actually all filled up last year. (Author’s note: The Canadian government established the research chair program in 2017 “in celebration of Canada’s 150th anniversary” with an initial investment of $117.6 million. Each awardee gets a seven-year appointment and up to $1 million for research annually.) There were only 25 of these chairs, and I think that we got over 10 times that number of applications. These were from very, very highly qualified researchers. There was an initial screen at the university level because they knew that it was a very high level, so you can imagine how many more researchers actually applied.

Canada’s 2018 budget included specific language for support for early-career researchers. What was the reasoning for carving out those funds, and will they be in future budgets?

Maybe I should just step a bit back and say that the present government believes that the way we’re going to prosper in the coming years — with what I guess everybody’s referring to as the fourth Industrial Revolution — is through science, research and innovation. For this, the skills training and capacity building are extremely important. The government wanted to make sure that we have funding and support for graduate students and postdocs to acquire the skills and to contribute in their best innovative and creative years.

The fact that we don’t have mandatory retirement has meant that the average age of researchers and professors in academic institutions is increasing. Of course, many of them, thankfully, are still very productive researchers. But then it just becomes a little bit of an uneven field for the young ones to compete with established investigators within the same pot of money.

To be consistent with the fact that we’re saying, “Hey. We’re opening up the country to the best researchers and scientists from around the globe,” we better make sure that they have funding to get their start. This was the thinking behind it. I think the government has made it clear that this is not a one-off.

One of the things that the U.S. has been grappling with is the lack of diversity in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Could you talk about diversity in STEM in Canada?

Though Mona Nemer’s expertise is cardiac biology, as Canada’s chief science adviser, she keeps up with all manner of scientific topics. In late August, she went to the Arctic. Here she’s seen on Petermann ice island, an iceberg cleaved from the Petermann Glacier off the northeastern tip of Newfoundland, with glaciologists from Laval University and the University of Ottawa.Diversity in STEM is a priority for the government, a priority for the minister of science and for the prime minister. We call these equity, diversity and inclusion policies. They’re targeted at increasing the number of women and the number from underrepresented groups — so groups, for example, with disabilities, people who identify as indigenous, visible minorities.

Though Mona Nemer’s expertise is cardiac biology, as Canada’s chief science adviser, she keeps up with all manner of scientific topics. In late August, she went to the Arctic. Here she’s seen on Petermann ice island, an iceberg cleaved from the Petermann Glacier off the northeastern tip of Newfoundland, with glaciologists from Laval University and the University of Ottawa.Diversity in STEM is a priority for the government, a priority for the minister of science and for the prime minister. We call these equity, diversity and inclusion policies. They’re targeted at increasing the number of women and the number from underrepresented groups — so groups, for example, with disabilities, people who identify as indigenous, visible minorities.

(Author’s note: About three-fourths of Canadians self-identify as having European roots, but the number of those who identify as indigenous is on the rise. Also, the country has one of the highest immigration rates in the world, and its immigrant diversity score, according to the Pew Institute, is greater than that of the United States.)

A year and a half ago, the government was unhappy that most universities had not achieved the aspirational targets that they had set. They actually demanded action plans from all institutions, and the institutions have until the end of 2019 to meet their targets. If they don’t, any application that does not contribute to these targets will not be reviewed and funded. This is one very clear and direct sort of policy or intervention.

One has to appreciate that higher education in Canada is under provincial jurisdiction. The federal government has to be careful about too much policy direction in that context. But nonetheless, because of the federal government raising the issue and its importance, the universities have voluntarily decided that they’re going to have targets for diversity and inclusion not only for the chair program but within the entire professorate and the staff within the universities.

The academic science community in the U.S. is dealing right now with gender bias and sexual harassment on campus.

I am always struck by the number of women — and they’re students, they’re young faculty, sometimes people involved with the research enterprise such as communications people, research assistants, and those who are part of the research landscape but not necessarily scientists — who just walk up to me and say how great it is to see that there are women scientists who occupy leadership positions.

I think that we will rest on the day when it’s so normal that nobody walks up to any woman in a leadership position and says how great it is, because I don’t think any guy walks up to a prime minister or a president and says, “Oh, isn’t it wonderful that we have a white man who’s a leader?”

In terms of the harassment on campuses, a year or a year and a half ago, the provincial government actually mandated that all universities have a sexual harassment policy. All universities had to develop and post them. That’s to say it’s a problem on all campuses, not just in the U.S. They’re tough issues to handle, but they’re also issues that need to be faced and managed, because for too long certain behaviors have been acceptable that should not be acceptable. I think that our universities are microcosms of our society, and it’s really important that we bring up the new generation in a climate of respect for each other and respect for diversity, for all humans.

We hear often from young scientists that they feel like their principal investigators are disappointed in them when they don’t want to become PIs. What are your feelings on that?

This is a very important point.

The whole idea that most Ph.D.s need to go to work at universities came when we started expanding higher education — probably in the 1960s and ’70s. But, I can tell you, all of us in university right now, if we reflect on who we trained with who has ended up in the academic sector, it’s never been more than 20 percent or 30 percent max.

My first job was not in a university. It was actually in a biotech company in Washington, D.C. The best people graduating in molecular biology at the time were not going to universities; they were going to the booming biotech sector. In chemistry, if all the Ph.D.s in the 1960s and ’70s had gone to academic positions, you would never have had any of the great chemical companies in the U.S. that not only sell products but do great research, like DuPont, not to mention the pharmaceutical industry.

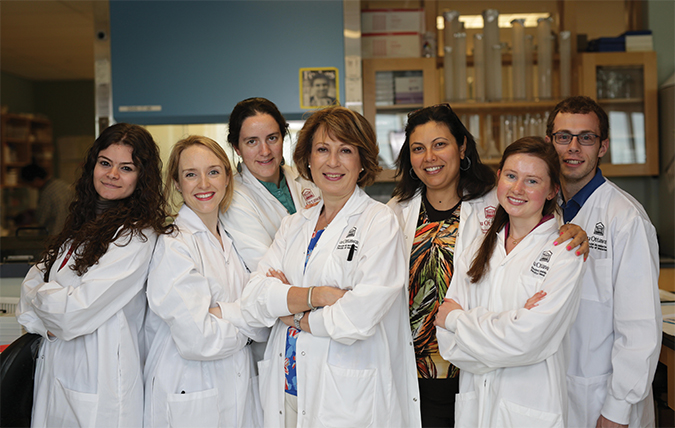

The idea that Ph.D.s have to go to a university and if they don’t go it’s a waste for them and society is terrible and actually goes against what we’re trying to do with the Googles of this world that will need to have these Ph.D.s to innovate. Not to mention the government scientists. How are we going to have government scientists doing proper science if all the good scientists are at universities? Mona Nemer, right, served as director of the Molecular Genetics and Cardiac Regeneration Laboratory at the University of Ottawa from 2006 until she was tapped by the Canadian prime minister to advise him and the nation’s science minister on scientific matters.

Mona Nemer, right, served as director of the Molecular Genetics and Cardiac Regeneration Laboratory at the University of Ottawa from 2006 until she was tapped by the Canadian prime minister to advise him and the nation’s science minister on scientific matters.

It’s a shame these young people feeling like they’re major disappointments when in fact they’re going to go off and do wonderful things.

It’s terrible. It may reflect the fact that all of us in academia need to open up our eyes to the reality of this world. Perhaps if we were a bit more engaged with colleagues outside of our institutions, we would stop having these kinds of attitudes and approaches that are totally counterproductive for society.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

In memoriam: Walter A. Shaw

He is the namesake for the Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research and founded Avanti Polar Lipids.

Dorn named assistant professor

She will open her lab at the University of Vermont in fall 2026, and her research will focus on catalysis, synthetic methodology and medicinal chemistry.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Kiessling wins glycobiology award

She was honored by the Society for Glycobiology for her work on protein–glycan interactions.

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.