An artist named Crick

The union of science and art is firmly underway. Artists and scientists are bonding over shared interests in discovery and experimentation, collaborating on shows and installations that ask fundamental questions about life processes and new technologies, and exploiting art’s potential to help make science more digestible.

For the artist Kindra Crick, this coming together is nothing new.

Crick’s first piece to intentionally fuse science and art was inspired by her love for her newborn daughter.KINDRA CRICK

Crick’s first piece to intentionally fuse science and art was inspired by her love for her newborn daughter.KINDRA CRICK Odile and Francis Crick attend a youth theater performance of "Hello Dolly" featuring their granddaughter Kindra in the title role.KINDRA CRICK

Odile and Francis Crick attend a youth theater performance of "Hello Dolly" featuring their granddaughter Kindra in the title role.KINDRA CRICK

Crick’s paternal grandfather is Francis Crick, co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, and her step-grandmother, Odile Crick, is an artist who drew the first published images of DNA that accompanied Francis Crick’s original paper with James Watson.

As part of a 2015 fundraiser for a new biomedical research center at the Francis Crick Institute in England, the late Nobelist’s granddaughter was invited to contribute a sculpture for auction. Provided with a blank, double helical structure and the theme “What’s in your DNA?” Crick chose to give each helix its own form. One side she painted a vibrant blue to which she added seedlike structures that twisted along the length of the helix and were meant to represent art and the infectious nature of human ideas. The other side featured handwritten diagrams copied by Crick from pictures of her grandfather’s chalkboards. She titled the piece “What Mad Pursuit.”

To Crick, the merging of both sides in the sculpture was not only complimentary, as DNA bases are, but integral to who her family is and who she has become.

A child of science and art

Crick was raised outside of Seattle in Bellevue, Wash., in what she calls “a very techie household.”

Kindra Crick’s piece "What Mad Pursuit" is an homage to her inherited love of science and art.ALEX CRICK

Kindra Crick’s piece "What Mad Pursuit" is an homage to her inherited love of science and art.ALEX CRICK

Both her parents and her maternal grandmother were programmers who encouraged experimentation, and the objects of science were never far from her play space. As a young child she was given chemistry kits and space in the garage for experiments.

Time spent with her paternal grandparents was formative. “My granddad would always encourage my curiosity and instilled in me a great love of books, puzzles and learning,” she says. “He taught me to question assumptions.”

Crick remembers there being a plethora of artist’s resources on hand when she’d visit Francis and Odile. “My grandmother would give me full access to watercolors, pastels, drawing, and would even hire models,” she says. “I had a much enriched opportunity to explore both disciplines.”

When it came time to choose a career, Crick opted for the science side of her interests, enrolling in the undergraduate program in molecular biology at Princeton. She enjoyed her coursework, but the actual research wasn’t all she’d hoped it would be.

“I always enjoyed lab work to some extent, but there was always something missing for me,” says Crick. “I like making things and building things.”

To meet her creative needs, Crick created posters and marquees for several theater groups on campus. After graduation, she spent time in a lab that studied the breast cancer-associated genes BRCA1 and BRCA2. While there, she found herself as intrigued by the imagery she saw under the microscope as she was by the work’s scientific questions.

When it came time to decide about graduate training, Crick felt tasked with arriving at her own research direction. But she stumbled. “When you’re in science you should pick a question, and I wasn’t sure if I had my question,” she says.

Instead of forcing herself into a lifestyle that wasn’t fitting, she enrolled at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The empathy molecule

Though she enjoyed both disciplines from an early age, Crick never thought to make science-informed art. “My art practice and my research had always been separate,” she says. But in 2007 she gave birth to a daughter and “became fascinated with the biological mechanisms that could be involved in the overwhelming sensation of love that one feels for a newborn.”

The curiously intense emotions helped to mesh fully her love of science and her love of art and led to the creation of pieces with scientific undertones. A new series of paintings delivered abstract concepts through schematic images resembling biology textbook diagrams. “I started using the concept of diagramming, but instead of it being factual and based on measurements it was very emotive,” Crick says.

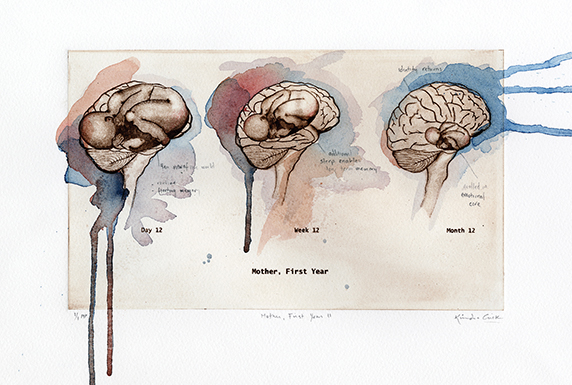

The first piece in this science-art fusion is called “Mother, First Year II.” It features three brains, each representing a different time after birth: day 12, week 12 and month 12. An image of a fetus is shown in the first brain, overwhelming all aspects. As time goes on, the fetus nestles inside the emotional core of the brain.

Crick got a range of reactions to the piece based on whether the viewer took the image literally or figuratively. Many who immediately understood the work tended to be parents themselves, while others asked her if the diagrams were backwards.

“One of the things about art is that you’re speaking to a very specific audience sometimes,” says Crick. “The art isn’t supposed to be taken literally.”

Postdoc researcher John Harkness and Crick with their collaborative piece inspired by perineuronal nets.KINDRA CRICK

Postdoc researcher John Harkness and Crick with their collaborative piece inspired by perineuronal nets.KINDRA CRICK

Art as outreach

Crick’s methods for creating her art bear some relationship to the scientific process. As she identifies new questions that interest her, she takes time to dig through research literature before getting started in the studio.

Although she now works explicitly with scientific concepts, Crick insists she isn’t making art that’s meant to teach audiences about science. During a recent partnership with NW Noggin, a group based in Portland, Ore., and founded by an artist and a neuroscientist who pair art with science outreach, Crick collaborated on a piece intended to inspire wonder.

Working with postdoc John Harkness of Washington State University, Vancouver, Crick created a sculpture that represents an aspect of Harkness’s research on perineuronal nets, which are believed to support the preservation of memory in neurons.

Titled “Your Joys, Sorrows, Memory and Ambition” — a phrase taken from a larger quote by her grandfather — Crick’s piece is a towering spectacle. More than eight feet tall, it features neuron cables interspersed with glowing LED lights encased by wire mesh nets. The wire nets cradle the neurons, visually depicting the supportive relationship perineuronal nets provide neurons within the human brain. Crick purposely exaggerated the net structures to draw attention to their important role.

In late April, 2016, as part of a weeklong outreach trip by NW Noggin, the piece was installed at The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., for an event that showcased the brain and our perceptions of beauty. While there, the group also performed science outreach at local schools to bring its joint science and art curriculum from the Pacific Northwest to the East Coast.

Connecting comfortably

As Crick moves forward with her art, the influence of science remains prominent. Her most recent series, “Cerebral Wilderness,” features old diagrams of brain anatomy overlaid with topographical maps of the Mt. Hood wilderness and diagrams of melting glaciers. The aged feel of the pieces evokes a sense of the continuity of nature and of scientific mystery.

Given her experience of motherhood, her formative time with her grandparents, and a life of separating, connecting and finally combining science and art, Crick is mindful of continuity and of her inheritance.

She’s learned, she says, that “not only do we pass on our genetics. We pass on our ideas.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

In memoriam: Walter A. Shaw

He is the namesake for the Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research and founded Avanti Polar Lipids.

Dorn named assistant professor

She will open her lab at the University of Vermont in fall 2026, and her research will focus on catalysis, synthetic methodology and medicinal chemistry.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Kiessling wins glycobiology award

She was honored by the Society for Glycobiology for her work on protein–glycan interactions.

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.