6 women biochemists you should know about

It's Women's History Month. There’s no better time to learn about some of the women who have shaped and are still shaping the field of biochemistry and molecular biology.

Jennifer Doudna: CRISPR gene editing

Jennifer Doudna at the University of California, Berkeley, has spent her career studying RNA enzymes, otherwise known as ribozymes. Her work is defined by the groundbreaking discovery, for which she shares a Nobel Prize with co-discoverer Emmanuelle Charpentier, of CRISPR gene-editing.

CRISPR gene-editing is performed by CRISPR–Cas9 complex. A Cas9 nuclease is complexed with guide RNA, which delivers Cas9 to the desired modification location in DNA to cleave at the specific site. This molecular biology technique revolutionized scientists’ ability to efficiently and accurately modify DNA in living organisms, which skyrocketed Doudna to the halls of fame and made her a role model for any young woman in science.

Doudna’s most recent efforts at the company Mammoth Biosciences, which she co-founded, include, among other things, working on a COVID-19 diagnostic using CRISPR technology to provide faster and less expensive results than traditional PCR testing.

Katalin Karikó: COVID-19 vaccine

Named one of Time Magazine’s 2021 Heroes of the Year, Katalin Karikó is a biochemist at the University of Pennsylvania. She has been recently recognized for her 2005 discovery (along with Drew Weissman) that nucleoside modifications suppress the immunogenicity of RNA, which allowed for the application of mRNA technology vaccines.

Karikó was born, raised and educated in Hungary. She emigrated to the U.S. when she lost funding as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Szeged. She took a postdoc position at Temple University in Philadelphia, where she studied double-stranded RNA.

Karikó transitioned to studies of messenger RNA when she moved to the University of Pennsylvania, where she worked with Elliot Barnathan (now executive director of research and development at the company Janssen).

Karikó had difficulty getting her research funded due to mainstream thinking that mRNA vaccines were an outlandish idea, and, despite multiple demotions and long hours (her husband estimated she made $1 an hour for how much she worked), she continued pushing until her 2005 breakthrough discovery.

As a further setback, despite publishing their findings, Karikó and Weissman’s discovery did not receive much notice until, a decade and a half later, the emergence of COVID-19 vaccines built on their findings.

Karikó now works for BioNTech, which made one of the vaccines, and remains a professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

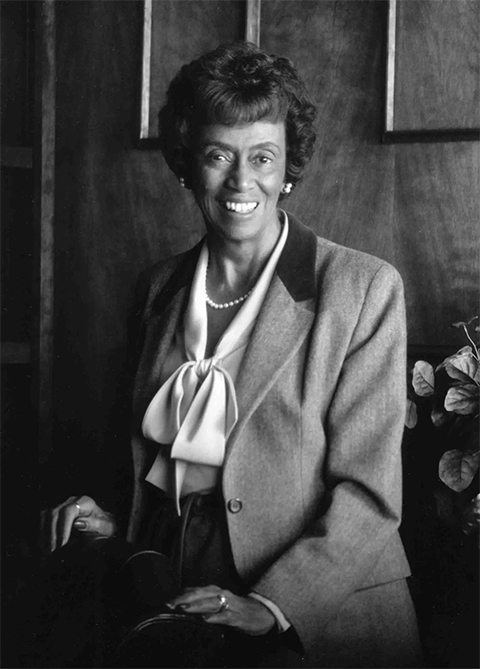

Jewel Plummer Cobb: Methotrexate and skin cancer

Jewel Plummer Cobb is best known for her discovery that the drug methotrexate was an effective treatment of certain skin cancers, lung cancers and childhood leukemia. She also was a pioneer as a Black woman in STEM.

Before taking a science class her sophomore year of high school, Cobb believed her path was physical education. But once she held a microscope, that changed everything. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in biology in 1947 from Talladega College in Alabama.

Cobb then was accepted to New York University’s graduate program in cell physiology but was denied a fellowship there due to her race. Cobb, whose father had been the first Black man to receive a medical degree from Cornell University, successfully pleaded her case to the biology faculty to receive the fellowship. She earned both her M.S. and Ph.D. at NYU.

Cobb studied tyrosinase, an enzyme required for melanin synthesis. She tested its use for producing melanin in the lab, which sparked a lifelong interest in melanin and skin cancer and ultimately led to her major discovery that the drug methotrexate can treat skin cancer.

She did research and taught at Sarah Lawrence College in New York and then became a dean at Connecticut College. At Rutgers University, she was dean of the women’s division. In 1981, she became president of California State University, Fullerton. She was the first Black woman to run a university west of the Mississippi.

She was elected to the National Institute of Medicine in 1974 and received a Lifetime Achievement Award for Contributions to the Advancement of Women and Underrepresented Minorities from the National Academy of Sciences in 1993.

Officials named a street in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, where she had a second home, after her in 2020, three years after her death.

Dorothy Andersen: Cystic fibrosis

Dorothy Andersen is not a familiar name to many in science, despite the fact that she was the first to discover cystic fibrosis. (Much more well-known for the same discovery is her protégé, Richard Hodges). Andersen’s work is finally receiving some attention, however, thanks to the podcast “Lost Women in Science,” which produced four episodes in 2021 detailing Andersen’s life and research — and theories as to why she became a lost woman in science in the first place.

Andersen graduated from John Hopkins Medical School in 1926. It was a time when few women became physicians. While she was interested in treating patients directly, women doctors then were ushered to behind-the-scenes positions. She worked most of her life as a pathologist.

Her 1938 discovery of cystic fibrosis came about while performing autopsies of children believed to have died from celiac disease. She noted many had lesions in the pancreas, which she termed cystic fibrosis. Later, she developed tests to diagnose cystic fibrosis, including the salt test (individuals with cystic fibrosis have difficulty transporting chloride across membranes, resulting in salty skin).

Andersen is hailed as one of the greatest women scientists of her time. Her work crossed multiple disciplines, including biochemistry, as she sought to characterize and treat cystic fibrosis. She defied gender discrimination despite limited opportunities for women of her time and extended countless lives.

Marguerite Davis: Vitamin A

Marguerite Davis earned her bachelor's degree in home economics from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1910. She completed some graduate work at the University of Wisconsin–Madison but never earned an advanced degree. Her tireless work with rats in the lab of Elmer McCollum at Madison, led to a discovery in 1913 of “a substance essential for life,” later termed vitamin A.

McCollum’s research was on nutritional chemistry; he was trying to find the best food to feed cows. But the easiest way to study this was by using rats, which is where Davis came into the picture.

Davis and McCollum gave rats food containing different fats — milk, olive oil and lard — and discovered only milk-fed rats grew well. They took this a step further by extracting the fat-soluble compound (vitamin A) from the milk and found that when feeding rats olive oil or lard with this fat-soluble compound added, the rats were able to grow healthily.

Gladys Emerson: Vitamin E

Gladys Emerson is best known for isolating vitamin E from wheat germ oil.

Emerson, who received bachelor's degrees in chemistry and physics as well as English, earned her Ph.D. in nutrition and biochemistry from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1932.

Emerson discovered vitamin E could be isolated from multiple sources, not only wheat germ oil, but also hydroquinone and synthetic alpha tocopherol. She tested the efficacy of vitamin E by feeding rats varying levels of compounds suggested to contain the vitamin.

Emerson went on to discover three forms of the vitamin (alpha, beta and gamma) and uncovered the link between vitamin E deficiency and muscular dystrophy using Guinea pigs.

Emerson was a revolutionary biochemist for her time, earning faculty positions, being recognized by President Nixon, and being considered one of the leading nutritional authorities of her time.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.

Simcox wins SACNAS mentorship award

She was recognized for her sustained excellence in mentorship and was honored at SACNAS’ 2025 National Conference.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.