Generating the 3T3 cell line,

the oncogene hypothesis and horses

The NIH 3T3 cell line is one of the mainstays of cell biology, gracing more than 26,000 publications in PubMed. But the only reason the embryonic mouse cell line ever got going, muses George Todaro, was that he was a young student who was willing to head into the laboratory every three days to transfer the cells whether they needed the transfer or not."One would have to be little crazy – or a graduate student," says Todaro with a laugh.

Todaro

Todaro

The cell line began in the early 1960s as part of a study to understand what properties governed the growth of cells in Petri dishes. Howard Green at New York University had just returned from a yearlong sabbatical at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, where he had learned about cell culture. Green decided to undertake a systematic study of culturing cells to understand better their growth properties. He took on Todaro, who was taking a year off from medical school to work in a research lab, to work with him on the project.

The problem with the existing cell lines at that time was that they"had very dubious history or no history," recalls Todaro. For a fresh start, Todaro and Green isolated fibroblast cells from a mouse embryo of the Swiss-Webster strain. The two researchers separated the cells into a series of Petri dishes and began to play around with conditions to see how they influenced cell growth.

To name the series of plated cells, they went with"3T3,""3T6,""3T12" and so on. The"3" denoted the number of days the cells were allowed to grow on the plates. The"T" stood for"transfer." The number after"T" referred to the hundreds of thousands of cells transferred to a new plate for each passage, as in 300,000 cells, 600,000 cells and 1.2 million cells.

The researchers noted that the cells in 3T6 and 3T12 plates grew over each other and got crowded to the point that they started to resemble tumors. But the 3T3 cells never reached confluence."They were strikingly different in that they were a single monolayer, a nice clean sheet of cells," says Todaro.

Out of all the permutations of cell density and culture conditions that Todaro and Green tried,"3T3 came through as an established cell line," says Todaro."I think the secret was we transferred them every three days whether they needed it or not. As a consequence, they never got confluent." He says that while most people wait for their cells to reach confluency to transfer them into fresh plates, he was willing to head into the lab every three days, whether it was a weekday, weekend or holiday, and do the transfer.

After medical school, Todaro landed a position as a principal investigator at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland. With his students, Todaro says,"I basically made them repeat the 3T3 strategy with NIH Swiss cells," which were cells taken from a different mouse strain.

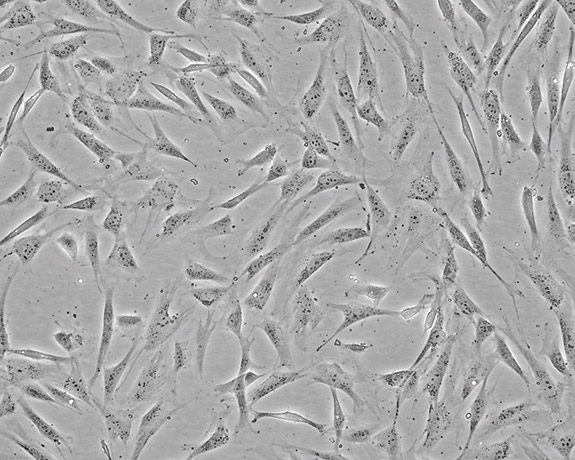

George Todaro's group at the National Cancer Institute established the NIH 3T3 cell line in 1969.Image courtesy of ATCC

George Todaro's group at the National Cancer Institute established the NIH 3T3 cell line in 1969.Image courtesy of ATCC

The new cell line from the NIH Swiss mouse embryo had the same property of being able to grow in flat monolayers, and"it had the further advantage of being highly transfectable by DNA, which the original 3T3 didn’t have," says Todaro. He adds there was a 3T3 cell line from a BALB/c mouse embryo but"the NIH 3T3 became the one of choice, because you could do a lot more genetic manipulations with it."

Along with establishing an important cell line, Todaro made other significant contributions to science. With Robert Huebner, he articulated the oncogene hypothesis in 1969. The hypothesis postulated that the human genome contained the information (oncogenes) that could be usurped by certain viruses to turn normal cells into tumorigenic ones.

For his work with oncogenes, Todaro was selected in 1970 as one of the"Ten Most Promising Men" (Mario Capecchi, who won the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 2007, and Elvis Presley were among the others). This annual award was given by the U.S. Junior Chamber of Commerce to recognize 10 notable young Americans. (The program, better known as the"Jaycees," later became the"Ten Outstanding Young Americans" to include women).

It’s about this point in his career that Todaro expresses regret in hindsight."This whole thing about the oncogene hypothesis – it would have been quite easy for us to have done the experiment that really proved it. We never did that." J. Michael Bishop and Harold Varmus did do the experiment and won the Nobel Prize for it."We should have done it," Todaro says."I thought it was obvious that it was going to work. I do really regret that. We had all the tools."

In the 1980s, Todaro left the NCI for a job at a biotechnology firm called Oncogene and has remained in industry since then. In the 1990s, he and colleagues developed an aerosolized version of an antibiotic called tobramycin. So far, it is the only approved inhaled antibiotic in the United States for treating lung infections – it changed the way cystic fibrosis patients were treated."When I look back on what I’ve done, I probably had more impact on cystic fibrosis treatment than anything else," notes Todaro. These days, Todaro works at a start-up biotechnology company called Targeted Growth to develop transgenic crops with better yields than current ones.

Besides science, Todaro’s other passion is racehorses. He caught the bug while living in Maryland and now is involved in breeding and horse racing. He says he sees similarities between his two passions."You have to make a decision based on incomplete evidence," he says. "But the difference with horse racing is you get a result in a minute and 10 seconds. With science, you go for years and years before you know if you’re following a useful path or if it’s another one of those dead ends."

Indeed, Todaro intertwines his twin passions closely: He named one of his mares Cell Line Forever.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

In memoriam: Walter A. Shaw

He is the namesake for the Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research and founded Avanti Polar Lipids.

Dorn named assistant professor

She will open her lab at the University of Vermont in fall 2026, and her research will focus on catalysis, synthetic methodology and medicinal chemistry.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Kiessling wins glycobiology award

She was honored by the Society for Glycobiology for her work on protein–glycan interactions.

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.