Stopping the devil in the dust

Most people who inhale the dust-borne fungal spores that cause Valley fever experience no symptoms. But in around 40% of people, the infection manifests, usually as pneumonia.

ASBMB Today asked John Galgiani, the director of the Valley Fever Center for Excellence, what the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic might mean for people in the Southwest and California’s Central Valley who are at risk of contracting both Valley fever and the new coronavirus.

“With respect to COVID-19, anyone with recently acquired Valley fever who then also gets COVID-19 infection might well have a bigger problem than someone who was only dealing with the viral infection,” Galgiani said. “However, for the many people with Valley fever infections years earlier, they should be at no more risk of COVID-19 complications.”

Rob Purdie knew something was amiss in early 2012 when headaches and sinus pain that were unresponsive to antibiotics began affecting his eyes. “I was having double vision,” Purdie recalled.

Purdie lives in Bakersfield, California, in the southern part of the fever’s namesake San Joaquin Valley. There, the fungal spores that cause Valley fever lie waiting in dense dust pockets for disruptions to carry them to a host.

Valley fever has been diagnosed as far south as Brazil, but the preponderance of cases occur in southwest Arizona — where spores can hitch a ride on increasingly frequent dust storms — and in Bakersfield, which is home to the Valley Fever Institute at Kern Medical, where Purdie sought treatment after enduring worsening headaches for five weeks.

“They got a lumbar puncture on me in the emergency department and said, ‘We think we know what you have,’” Purdie said.

His formal diagnosis was disseminated coccidioidal meningitis, which occurs when spores escape the lungs and travel up the spinal cord to the brain’s outer membrane. Left untreated, this stage of Valley fever is fatal. Purdie had few options. Doctors often prescribe broad antifungals, which stop the fungi from replicating but don’t kill them outright.

Each year, tens of thousands of people in Arizona and California are diagnosed with Coccidioides infection. The number is likely far higher, but most go undiagnosed due to the fungi’s asymptomatic or flulike presentation.

By the estimates of John Galgiani, director of the University of Arizona’s Valley Fever Center for Excellence, nearly one in four cases of pneumonia in Arizona are caused by Coccidioides.

“Each year, 1% of the population of the area has an acute or long-term brush with Valley fever,” he said.

Since the end of World War II, scientists have tried and failed to develop a vaccine. In 1985, the most promising candidate provided poor protection and caused swelling at the injection site.

Today, two promising vaccine candidates are nearing human trials. But as the American West continues to heat up and dry out along with the rest of the world, the greatest hurdle to protecting millions of people across Valley fever’s increasing range will likely be funding rather than immunology.

Spores and soil

While the Sonoran and Mojave deserts that stretch across Mexico and the southwestern United States are the ones most known to harbor Coccidioides, the pathogen’s range is expected to expand by the end of the century, according to a paper published in August in the journal GeoHealth.

Morgan Gorris, a postdoctoral fellow at Los Alamos National Laboratory, was the first author on the paper about the pathogen’s range if climate change continues unabated. “In our baseline model, looking at where Valley fever is currently, we estimated that the fungus is probably in 12 states, and by the end of the 21st century that could increase up to 17 states,” Gorris said. “And, as a result, the number of Valley fever cases could increase by up to 50%.”

The fungus already has crept into the desert portions of Washington, and is believed to potentially also be in eastern Oregon, Gorris said. Additionally, a 240% increase in the incidence of dust storms in the Southwest between the 1990s and 2000s, possibly from climate change, was found to coincide with an 800% increase in cases of Valley fever between 2001 and 2011.

The pathogen’s current and future ranges are influenced by species diversity. The two species of Coccidioides, C. immitis and C. posadasii, are morphologically identical, but their growth rates diverge in different salt concentrations. This may be what limits C. immitis to the Central Valley but expands C. posadasii’s range to northern Mexico and parts of South America.

At Northern Arizona University, biology professor Bridget Barker puzzles over what drove the cocci species to infect mammals.

“We’ve done a lot of soil sampling, and it looks like burrows in general for any type of animal seem to be more frequently positive than just a random soil sample,” she said.

She added: “Pretty much any mammal that gets exposed is potentially at risk for disease, even like dolphins off the coast of California.”

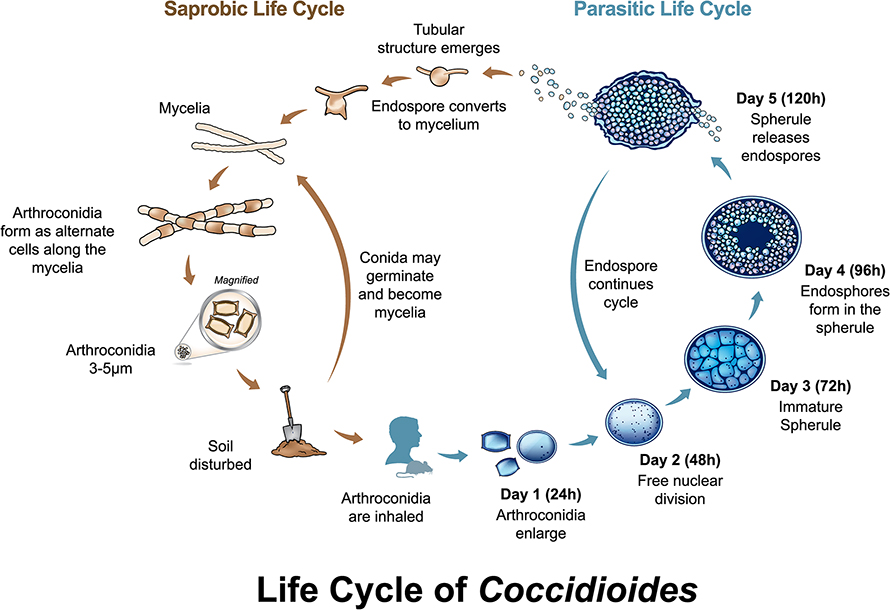

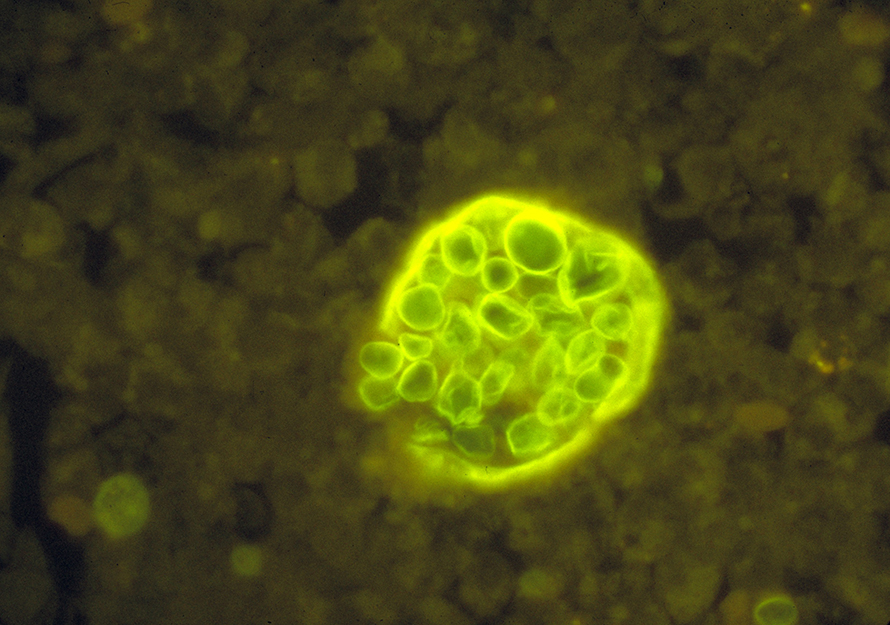

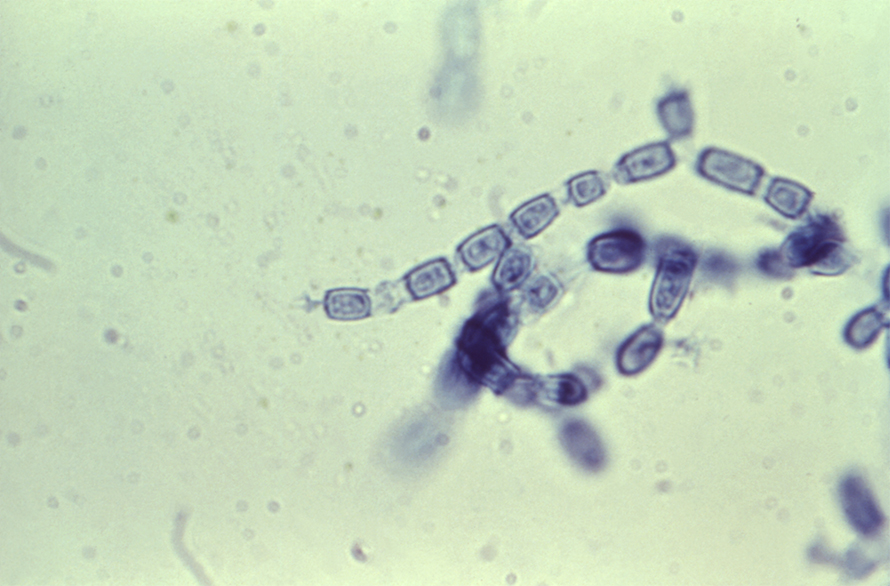

The fungi’s life cycle is unique to the Coccidioides genus: It persists in soil as filamentous hyphae, then becomes infectious arthroconidia that enlarge to spherules upon inhalation, which rupture to send out endospores that grow to form spherules in adjacent tissues.

of coccidioides.

“The host has to inhale those spores from the soil. And when the spores are inhaled, they undergo a huge change, so it’s basically a whole different structure inside the host,” Barker said. “There's no other fungus that we know that makes that same structure; what are the evolutionary pressures that lead to that?”

A few years ago, Barker had a brush with Valley fever while taking samples in the field. Her dog and her husband also have been infected.

“My dog got it. My husband got really sick,” she said. “We had been camping, my dog was digging up a rodent burrow, and dust was going everywhere.”

Fortunately for Barker, the disease never progressed beyond the granuloma in her lung.

“Without going in and doing a lung biopsy, they couldn't prove it … and there’s always the possibility with going and getting a biopsy that you could collapse your lung,” she said. “I thought it was best to just leave it alone, and that’s my natural vaccination.”

While Barker and her collaborators continue to examine the prevalence of cocci in soil samples in the southwestern United States, Mexico and South America, she also has her eyes trained on deserts in Africa and Asia and the novel fungal pathogens that might inhabit them.

“There are close relatives,” she said, “but whether we see the same thing in other areas in Asia and in Africa, Australia … I would say the prediction is yes, but I don’t know exactly what those organisms would be.”

In lieu of a cure

David Davis isn’t sure where he was exposed to the spores that gave him coccidioidal pneumonia last summer, but he has a hunch.

“I’d been running right next to a dry riverbed and through an excavation site,” said Davis, a 51-year-old Navy veteran and nurse who works in the operating room at Kern Medical in Bakersfield.

Davis, a runner and weight lifter, began to feel the effects of Valley fever while he was at work: “I was moving a patient from the operating room table back to the gurney to go to recovery, and I was shaking, sweating; my joints hurt, and I was out of breath.”

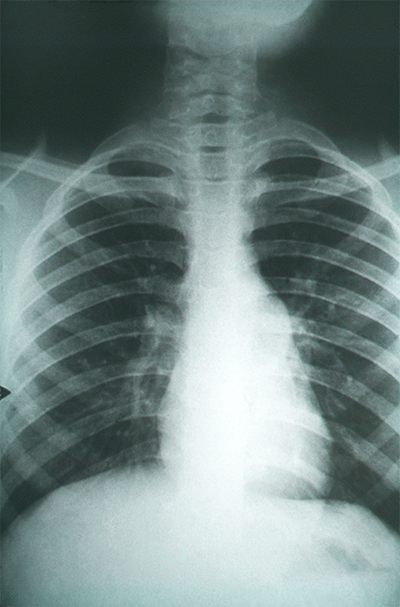

After an X-ray turned up a lung mass, his primary care provider ordered a blood test for cocci.

“When I received that phone call, I was out in the dirt with my fiancée trying to exercise,” he said. “I was like, ‘Well, I probably shouldn’t be right here in this dusty field.’”Like many people who come down with Valley fever, Davis had a relatively straightforward recovery. He began a daily regimen of 200 milligrams of fluconazole prescribed by his primary care physician. Then Royce Johnson, the medical director of Valley Fever Institute, increased his dosage to 800 milligrams. By November, the pathogen’s levels were low enough that Davis was off fluconazole, which had been causing him to lose the hair on his arms and legs.

But because fluconazole doesn’t kill cocci outright, Davis has lingering amounts of cocci in his body that his immune system will have to fight off.

“I was running up to 20, 30 miles a week. And now I run maybe eight, and I’m pretty tired still,” he said. “So I think it’s going to take a while for me to get back to the level, if ever, where I was before.”

Like Davis, Judy Kingma, whose house in San Luis Obispo backs up to a field, believes she was exposed to spores in soil that had become dislodged by nearby construction.

“I’ve lived here for 25 years and never had a problem,” she said. “And then just last year, this construction site is how I’m sure I got it.”

Kingma had been traveling to the University of California, Los Angeles, to receive treatment and surgery for pheochromocytoma, a rare tumor of the adrenal glands. Not long after the tumor had been successfully removed, however, Kingma's oncologists noticed severe swelling of the lymph nodes in her chest. After months of testing failed to turn up evidence of metastasis, her physicians recommended she undergo a mediastinoscopy to open up her chest and biopsy the lymph nodes, which ultimately cost $25,000.

Lung scarring worsens as the fungal infection does.

“Everyone just thought I had lung cancer because, you know, you get this nodule in your lungs,” she said. “That just blew my mind, like it’s an $80 test blood test versus a knife.”

After she was diagnosed with disseminated Valley fever, she began driving the 2.5 hours each way to Bakersfield to seek treatment at Kern Medical, where doctors increased her dose of fluconazole from 400 mg to 600 mg.

“They monitor me pretty closely,” she said. “I have a lung X-ray every time I go there, about every two months.”

Kingma is continuing to take fluconazole, with its unpleasant side effects, to keep the fungi’s growth in check while her immune system gradually clears the cocci from her body.

“Your skin turns into like leather, your hair falls out,” she said. “And it gets very expensive. All from just a little disease where people think, oh, you take a few pills and you’re all better.”

Fungal firsts

The lack of an FDA-approved vaccine against any infectious fungus is a consequence of both the rarity of eukaryotic pathogens and the difficulty of developing vaccines for them.

The first vaccine that was developed for Coccidioides, which used formaldehyde-killed fungal spherules, stalled during clinical trials to evaluate its safety in 1985.

“There’s a lot of carbohydrate in (the 1985 candidate), and it’s really irritating. And it’s just not acceptable,” explained Lisa Shubitz, a veterinarian and research scientist at the Valley Fever Center for Excellence.

However, the human immune response to Coccidioides infections still makes the pathogen an ideal vaccine target.

“Many people get infected and either have no symptoms or get symptoms which go away on their own,” Galgiani said, “and then they’re protected for the rest of their lives, (which) makes the idea of the vaccine very appealing.”

In 1997, a funding committee affiliated with California State University called the Policy Advisory Committee for the Valley Fever Vaccine Project chose five scientists to pursue vaccine research; their five avenues of generating immunity bore out the two vaccine candidates nearing their final stages of development.

Mark Orbach, a fungal geneticist and mycologist at the University of Arizona and longtime collaborator with Galgiani, has helped develop one of those vaccines.

Orbach began this project with Coccidioides after colleagues at Cornell University performing random insertional mutagenesis knocked out a gene in a fungal maize pathogen that reduced its virulence by 60%. They then found that Coccidioides possessed an ortholog of that gene, and named it CPS1.

Orbach, who was working on a fungal rice pathogen at the University of Arizona, began working on pathogenicity in coccidioides that had the CPS1 gene knocked out, which he and colleagues named delta-CPS1. The researchers, together with scientists at the University of Kansas, Colorado State University and the pharmaceutical company Anivive Lifescience, are using those fungi to develop a vaccine.

“The vaccine itself is just spores that we harvest off of plates, clean, wash, purify separate from hyphal filaments, and then suspend in an aqueous solution,” Orbach said. Developing a vaccine commercially requires a fine-tuned mixture of other ingredients, however, to ensure that the suspended spores can remain on a shelf for six to 12 months.

According to Galgiani, mice that have been bred to replicate genetic mutations that predispose people to severe symptoms of Valley fever have been protected by the delta-CPS1 vaccine. But before the vaccine can begin human trials, it must be evaluated further in animal trials, which Shubitz has helped run.

Coccidioides in canines

Shubitz treats hundreds of dogs for Valley fever every year.

adopted a new dog, Journey, in mid-2018.

“There’s a high need for a Valley fever vaccine in this species,” she said. “Treatment is expensive. It can fail, and Valley fever is a very common cause of relinquishment of pets.”

Depending on individual cases, a diagnosis alone can cost hundreds to thousands of dollars; treatment, which can last six to 12 months, can then cost several thousand dollars.

“The medication may cost $50 to $100 a month, even if you use the least expensive medication,” Shubitz said. As in humans, the most widely used antifungal is fluconazole, followed by the similar but pricier compound itraconazole.

Around 25% of dogs with Valley fever suffer severe complications, a rate more than twice that of humans. According to Shubitz, this may be a consequence of their curious noses.

“Dogs may inhale larger doses (of the fungus) than humans on a routine basis, and that could contribute to the increased rate of clinical disease and complications, because their faces are in the ground all the time,” Shubitz said.

While these rates are suspected to be higher than those of their closest native kin, coyotes, surveillance of wild animals, including mountain lions and other mammals, leaves the picture incomplete. “We don’t know that much about coyotes, because if they die in the wild, no one knows about it,” she said.

Shubitz and her colleagues recently wrapped up a clinical trial of the delta-CPS1 vaccine in dogs. While the results have yet to be released, Shubitz was optimistic about how the animals tolerated it.

“(This) should not cause a significant kind of a reaction. The mice don’t care about it. The dogs had no reaction.”

Better drugs

Both dogs and humans largely are limited to two categories of antifungals, prescribed off label, to treat Valley fever: the -azoles, which include fluconazole and posaconazole, and amphotericin B. They keep cocci in check, but long-term treatment can become expensive. The average lifetime cost of treatment for a person with Valley fever is estimated to be $94,000.

AT KERN MEDICAL

Since 2012, Purdie, who is now the patient/program development coordinator for the Valley Fever Institute at Kern Medical, has received injections of amphotericin B through a port called an Ommaya reservoir on the top of his skull.

“Some people get it three times a week,” said Purdie, who is one of the roughly 2,400 patients who visit Kern medical for coccidioidomycosis each year. “I’m really lucky. I go in about once every eight weeks.”

Like fluconazole, which was developed to treat the candida fungi that cause thrush, amphotericin B only keeps the fungi from replicating, rather than killing them. A recent clinical trial to evaluate finally the efficacy of fluconazole against coccidioidomycosis ended after falling short of the 1,000 patients it had sought to enroll.

Galgiani has been instrumental in the development of a drug, nikkomycin Z, which kills Coccidioides outright by interfering with the synthesis of chitin in their cell walls and has been evaluated in both dogs and humans. But both he and Shubitz — who collaborated with Galgiani to evaluate Nikkomycin Z in dogs — raised concerns about the high cost of completing clinical trials needed for FDA approval.

“I don’t know whether that drug will ever reach market,” Shubitz said.

Outside the Valley

At the Applied Biotechnology Institute in San Luis Obispo, California — well north of Bakersfield and roughly 600 miles northwest of Tucson — John Howard is formulating another vaccine to protect against Valley fever.

Rather than a killed or live-attenuated vaccine like the 1985 candidate or CPS1, ABI is developing a subunit vaccine, a formulation that uses the smallest component of a pathogen that’s able to elicit an immune response. For Coccidioides, that’s Antigen 2, an immunoreactive component discovered simultaneously by mycologists at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio and at the Valley Fever Center for Excellence in the 1990s. By growing large quantities of the protein, referred to as Ag2/PRA, in corn and incorporating it into an edible wafer, Howard and his colleagues have created an oral vaccine.

“Oral delivery is important, because in the immune system, it gives a good mucosal response,” Howard said. That immunological response includes the mucosal membranes that line the respiratory tract, which are most likely to come into contact with Coccidioides spores. “Most injections give you little or no mucosal response.”

Howard, who has been working with transgenic maize for more than 40 years, was fine-tuning ABI’s oral vaccine for hepatitis B when he first encountered Valley fever.

“Several years ago, my sister-in-law got sick with Valley fever, which was the first I’d heard of it,” he said. “We said, ‘Wait a minute, this is a fungal pathogen.

There are no fungal vaccines.’ So we started looking into it.”Howard reached out to Gary Ostroff, a professor at the University of Massachusetts Medical School specializing in small-molecule delivery technologies, and Chiun-Yu Hung at UTHSA, who had been continuing the institution’s research into Coccidioides and Ag2. While their groups had been successful in growing and harvesting Ag2 from Escherichia coli, they had been hampered by the relatively low yield of the system.

“One of the big problems was that they can’t produce very much of it in microbes,” Howard said. He and his colleagues then transformed the gene for Ag2 into a maize line they already had been using and brought in a chemist from San Francisco State University, Raymond Esquerra, to assist with the process of extracting the protein from the corn. Their results, published in the Journal of Infectious Disease in July, were promising. “We got about 100 times more (Ag2) than they can get out of the microbial system.”

The next steps for Howard and his colleagues are to fine-tune the processing of the Ag2 protein and to test the oral vaccines in animals.

Kamaljeet Kaur, a graduate student in Raymond Esquerra’s lab at SFSU, had planned to describe improvements to the extraction process at the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology’s annual meeting in San Diego before the meeting was canceled.

“We have tried using different detergents, and we have tried using liquid nitrogen, which is very impactful in getting the maximum extraction,” Kaur said.

And in a paper recently published in the journal Vaccines, Howard, Hung and Ostroff found that mice that were simultaneously given the vaccine candidate both by injection and oral routes fared better against Coccidioides than mice that only received the vaccine candidate by one route.

Funding the finish

While projections indicate that a vaccine for Valley fever could be profitable, they do not take into account the high costs of guiding a vaccine through clinical trials, Galgiani said.

“It’s not biology. It has to do with market forces and capitalism and how things get made,” he said.

One factor is the small size of the susceptible U.S. population relative to the global populations that vaccine manufacturers target to make back their production costs.

“Think about vaccines that people make for tetanus or influenza and who gets them — everyone in the world. Those are considered vaccine markets,” Galgiani said. “And if you have a population that would benefit from a vaccine being in the range of, say, 25 million people, that sounds like a lot of people, but it’s a small vaccine market.”

A 2000 report by the National Academies titled “Vaccines for the 21st century: A tool for decision-making” estimated it would require 15 years and $360 million to develop and license a vaccine for Valley fever, money that has failed to materialize over the past two decades.

U.S. Reps. Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., and David Schweikert, R-Ariz., who chair the Congressional Valley Fever Task Force and whose districts include Bakersfield and the northeastern suburbs of Phoenix, respectively, recently secured $2 million for Valley fever surveillance and research, but those funds, and the money they’ve raised in the past, fall an order of magnitude short of what’s needed to bring a vaccine to fruition.

While financial barriers remain for taking a vaccine candidate through human trials, the researchers at the Valley Fever Center for Excellence have partnered with the pet-focused Anivive Lifesciences to shepherd the vaccine through the remaining animal trials. Orbach and his colleagues recently submitted paperwork to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Center for Veterinary Biologics, which regulates and approves vaccines and biologics for animals, for a provisional license to begin producing the vaccine.

“We feel that we’ve demonstrated safety and effectiveness. But really the USDA Center for Biologics are the people who have to decide that, and we’re hoping that we’ll be able to get approval by 2021," Orbach said.

“The cost is very high, so we feel that it’s probably going to require government interest to help support a regional vaccine for people. And we’re optimistic that we can convince them that it’s a worthwhile expense.”

Coccidioidal inequities

Researchers are attempting to unravel why certain populations, including people of Filipino and African descent, are hit harder by Coccidioides infections than others.

“Some strains cause very severe disease; some strains don’t,” Bridget Barker at Northern Arizona University said. “So there’s clearly some genetic aspects in the fungus.”

The amount of fungal spores a person is exposed to also plays a role.

“If you inhaled 10 spores, you’re probably basically vaccinated. If you inhaled a million, that could end very badly for you,” she said. “We think that, in some of these outbreaks that they’ve had, like archaeological digs or construction sites, they just happened to hit a pocket where there’s a bunch of the organism and released maybe millions of spores all at once.”

At the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, Steve Holland, the director of the NIAID’s division of intramural research, has been recruiting people at high risk for developing disseminated or refractory coccidioidomycosis, the more severe forms of the disease.

“We’ve identified now a fair number of genes that are involved in disseminated coccidioidomycosis, some of which we’ve reported in the past,” Holland said. Those genes include ones that code for the cytokines STAT1 and STAT3, which are essential for the production of the cytokines interferon gamma, interleukin-12 and interleukin-1 in response to infection with Coccidioides."

“In our current study, we’ve been looking at genes and mutations which are potentially a bit more common, but what makes cocci different is that you have an organism of relatively high virulence. But it’s also geographically circumscribed,” he said. “So if you grew up in Chicago with a high-level cocci susceptibility gene, that doesn’t matter until you go to cocci territory. And trying to sort those things out is really what we’re interested in.”

According to Holland, the trial currently has recruited 65 participants of a targeted 200.

“I think we have genetic associations for about half of them. Which is pretty good for us,” he said. “This is a disease that is being very actively studied both at the pathogenesis level and at the treatment level, and I’m absolutely confident that in the next couple of years, we’re going to know a lot more about why people get sick and a lot more about how to treat them.”

Multiple appeals

In recent years, the federal government and the California state prison system have been sued by inmates left debilitated by Coccidioides and by families of inmates who died from exposure to it.

Ben Pavone, an attorney based in San Diego, is lead counsel for a case brought by 270 former and currently incarcerated people who contracted Valley fever while at state prisons in the Central Valley. They have been trying to sue prison officials, the former head of state prisons and former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger.

In February 2019, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the lawsuit on the grounds that the defendants reasonably could have concluded that the threat to inmates from the disease was not severe given that millions of people are exposed to Valley fever in California every year.Pavone appealed that decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined in October to hear the case.

According to Pavone, the 9th Circuit overreached by applying qualified immunity to the prison officials. The doctrine shields government officials from being sued for discretionary actions related to their line of work.

“It’s a get-out-of-jail card for every time the government makes a mistake,” Pavone said.But the ruling by the 9th Circuit Court gave Pavone another pathway for redress: suing a state-run corporation appointed in 2006 to take control of prisoners’ medical care after the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation failed to meet the standards against cruel and unusual punishment set by the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Pavone’s next legal move will take advantage of an earlier decision he made to split his clients into two groups of 110 and 160 each. While Pavone takes his case about the mistreatment of the initial 110 inmates against the state’s receiver, he also will file a suit covering the remaining 160 clients similar to his initial suit. This time, he said, he intends to bring a tighter case against the prison system and the doctrine of qualified immunity.

“There are two pieces of good news,” Pavone said. “One, my 110 guys have another shot … and, two, we’re taking a shot at qualified immunity.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Cracking cancer’s code through functional connections

A machine learning–derived protein cofunction network is transforming how scientists understand and uncover relationships between proteins in cancer.

Gaze into the proteomics crystal ball

The 15th International Symposium on Proteomics in the Life Sciences symposium will be held August 17–21 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

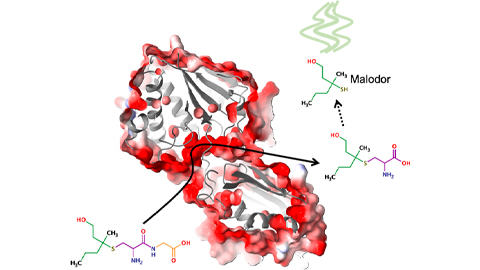

Bacterial enzyme catalyzes body odor compound formation

Researchers identify a skin-resident Staphylococcus hominis dipeptidase involved in creating sulfur-containing secretions. Read more about this recent Journal of Biological Chemistry paper.

Neurobiology of stress and substance use

MOSAIC scholar and proud Latino, Bryan Cruz of Scripps Research Institute studies the neurochemical origins of PTSD-related alcohol use using a multidisciplinary approach.

Pesticide disrupts neuronal potentiation

New research reveals how deltamethrin may disrupt brain development by altering the protein cargo of brain-derived extracellular vesicles. Read more about this recent Molecular & Cellular Proteomics article.

A look into the rice glycoproteome

Researchers mapped posttranslational modifications in Oryza sativa, revealing hundreds of alterations tied to key plant processes. Read more about this recent Molecular & Cellular Proteomics paper.