Study sheds light on how a drug being tested in COVID-19 patients works

A team of academic and industry researchers is reporting new findings about how exactly an investigational antiviral drug stops coronaviruses. Their paper was published the same day that the National Institutes of Health announced that the drug in question, remdesivir, is being used in the nation’s first clinical trial of an experimental treatment for COVID-19, the illness caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Previous research in cell cultures and animal models has shown that remdesivir can block replication of a variety of coronaviruses, but until now it hasn’t been clear how it does so. The research team, which studied the drug’s effects on the coronavirus that causes Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, reports that remdesivir blocks a particular enzyme that is required for viral replication. Their work was published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

All viruses have molecular machinery that copies their genetic material so they can replicate. Coronaviruses replicate by copying their genetic material using an enzyme known as the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Until now, it has been difficult to get the polymerase complex, which contains multiple proteins, to work in a test tube.

“It hasn’t been easy to work with these viral polymerases,” said Matthias Götte, a virologist and professor at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, who led the JBC study. That has slowed research into the function of new drugs.

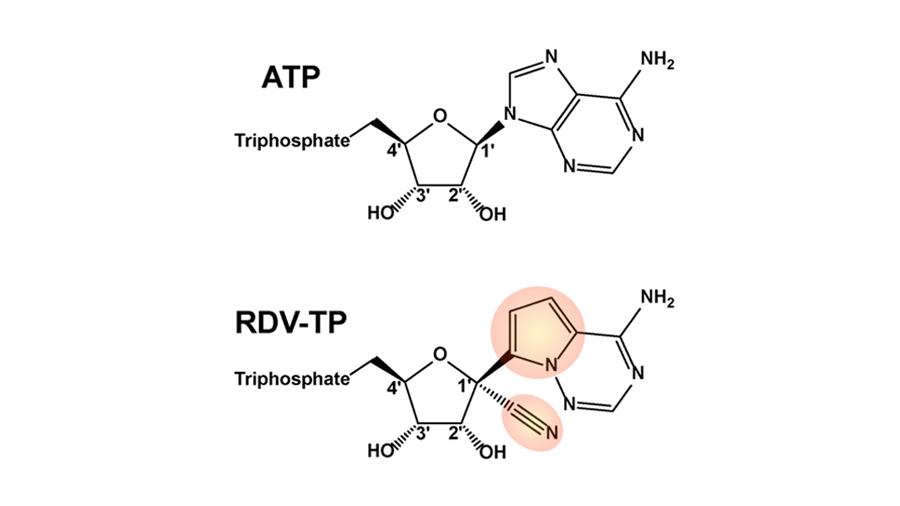

Using polymerase enzymes from the coronavirus that causes MERS, scientists in Götte’s lab, including graduate student Calvin Gordon, found that the enzymes can incorporate remdesivir, which resembles an RNA building block, into new RNA strands. Shortly after adding remdesivir, the enzyme stops being able to add more RNA subunits. This puts a stop to genome replication.

The scientists hypothesize that this might happen because RNA containing remdesivir takes on a strange shape that doesn’t fit into the enzyme. To find out for certain, they would need to collect structural data on the enzyme and newly synthesized RNA. Such data could also help researchers design future drugs to have even greater activity against the polymerase.

Götte’s lab previously showed that remdesivir can stop the polymerase in other viruses with RNA genomes, such as Ebola. But, Götte said, the molecules that remdesivir and related drugs mimic are used for many functions in the cell. This paper supports the viral RNA polymerase of coronaviruses as a target.

Remdesivir, which is manufactured by the American company Gilead Sciences, has not been approved as a drug anywhere in the world. According to Gilead, results from a clinical trial with COVID-19 patients in China are expected in April.

The JBC study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Alberta Ministry of Economic Development, Trade and Tourism. Two of its authors are Gilead scientists, because Gilead provided a form of the investigational drug free of charge. Götte has previously received funding from Gilead Sciences to support a study of remdesivir’s effect on enzymes from ebolavirus.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.