Unlocking the mystery of our genome and ancestry using art

Visual artist Lynn Fellman’s journey into the world of biological science illustration began in 2005 with a cotton swab.

Her interest was piqued while participating in National Geographic’s Genographic Project. The goal of the project was to use direct-to-consumer DNA-testing kits to reveal insights into these age-old questions: How did modern humans evolve and how did we migrate to populate the Earth?

Her interest was piqued while participating in National Geographic’s Genographic Project. The goal of the project was to use direct-to-consumer DNA-testing kits to reveal insights into these age-old questions: How did modern humans evolve and how did we migrate to populate the Earth?

“I saw how the scientists were going to put genetic data with fossils to understand human evolution,” says Fellman. “Unlike any of the other (direct-to-consumer DNA-testing) projects for ancestry, Genographic is the only one that pairs anthropology with genetics for a much richer picture of prehistory.”

Curious about her DNA’s origins, Fellman, who lives in Minneapolis, ordered the kit and sent her two buccal swabs back to the Genographic project for analysis. She was not surprised by her Northern European ancestry results, but something else grabbed her attention: “My fascination was the molecular story — what scientists now refer to as molecular anthropology — that revealed prehistoric information that we had not (gotten and) could not get from fossil remains.”

Fellman’s curiosity led her to create art using her results. “The first pieces with my own (mitochondrial) DNA data showed my haplogroup route on a map of Africa and Europe. I’m haplotype H— no surprise, since 30 (percent) to 40 percent of (women) with Northern European decent are in the H haplogroup,” she says.

Fellman’s curiosity led her to create art using her results. “The first pieces with my own (mitochondrial) DNA data showed my haplogroup route on a map of Africa and Europe. I’m haplotype H— no surprise, since 30 (percent) to 40 percent of (women) with Northern European decent are in the H haplogroup,” she says.

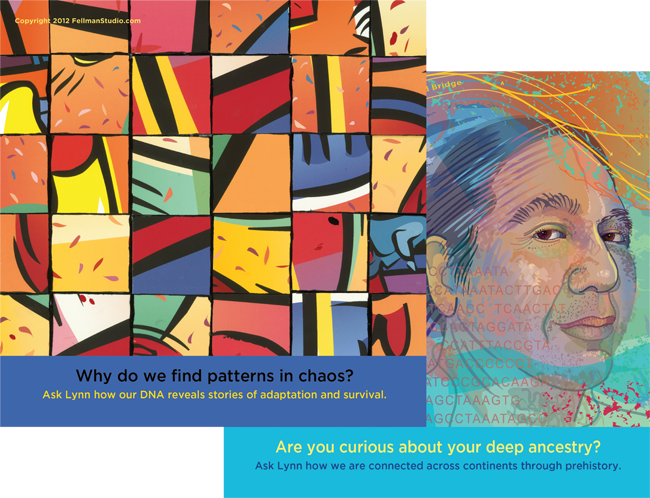

Her haplogroup artwork led to the “DNA Portrait” project commissioned by the University of Minnesota. She created a series of portraits and wrote companion storyboards, telling the ancestry of several members of the Urban Research and Outreach Engagement Center located in north Minneapolis. Using family history and DNA results from the Genographic Project, Fellman created a visual narrative for each participant.

Fellman, who received a degree in studio arts from the University of Minnesota, previously earned her living as an independent designer creating print materials and interactive multimedia presentations. Her work always starts out the same way: with “pencils and a stack of 8½-by-11-inch white paper, writing and sketching until I have something surprising, something that looks just right.” From there, Fellman imports her art using digital software tools and adds layers of color and texture.

Fellman set out to ground her art in science. She learned how to read research papers and subscribed to journals like Science and Nature. She also found a mentor, Perry Hackett, a genetics professor at the University of Minnesota. Fellman’s understanding of genomic science enabled her to communicate with scientists. “I could speak their language, understand most terms, and was aware of some publications — so the conversation could skip the basics and lead to what their work was really about,” she explains.

Fellman adds: “The ability to translate difficult concepts into visual images that convey the message is just what I do with scientific research. It feels like I’ve been preparing to focus on science for most of my career.”

Fellman adds: “The ability to translate difficult concepts into visual images that convey the message is just what I do with scientific research. It feels like I’ve been preparing to focus on science for most of my career.”

In 2011, Fellman illustrated a video slideshow and wrote a corresponding script commissioned by the American Association for the Advancement of Science for its Member Central website. In the video, titled “At the Crossroads: Finding Family in Bones and Genes,” she explains how fossils and genes come together to provide a more complete story of human evolution based on the draft sequence of the Neandertal genome as published in Science in 2010 .

Her multimedia art earned her an invitation to give a talk on her work at the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution’s meeting in Dublin in 2012. “It was a thrill and an honor,” she says of giving a talk about her work on paleogenomics at the meeting. “The room, which seats about 100 people, was almost filled. I asked to have all the lights turned off, so when entering all you saw was the large screen with my first slide — big eyes in a face staring right at you. The scientists seemed to enjoy it,” she recalls

One of the best outcomes from that meeting was her current fellowship at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center in Durham, N.C. NESCent is a cross-disciplinary center that addresses novel emerging topics of evolutionary research. While at NESCent for the remainder of the year, she is working on two projects with the challenge of presenting “complex information for two different audiences in different media with new images in an engaging way.”

The first project is an adult-geared lecture entitled “Visions of Neanderkin: Comparing Ancient and Modern Genomes.” She bases her lecture on the newer sequence data of the Neandertal and Denisovan genomes, specifically “the analysis of the ancient (hypervariable) regions that is underway at a number of labs.”

The first project is an adult-geared lecture entitled “Visions of Neanderkin: Comparing Ancient and Modern Genomes.” She bases her lecture on the newer sequence data of the Neandertal and Denisovan genomes, specifically “the analysis of the ancient (hypervariable) regions that is underway at a number of labs.”

Fellman’s second project is an iBook for children and their parents. Entitled “I Am a Multi,” it blends narrations, digital painting and haikulike text about “a young girl whose parents came from different and distant geographic locations,” she explains. “This is another way to tell the story of human evolutionary history and make it relevant to all of us.”

Questions about who we are, where we came from and how we evolved fascinate artists and scientists alike. Fellman’s goal is to inspire wonder and understanding of the fundamental ideas and intrinsic beauty found in human gene stories. “Our DNA shows how we are all connected in tangible ways, and that makes our individual stories part of something much bigger.”

For more information about Fellman and her art, visit her website at www.fellmanstudio.com.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Kiessling wins glycobiology award

She was honored by the Society for Glycobiology for her work on protein–glycan interactions.

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.

Simcox wins SACNAS mentorship award

She was recognized for her sustained excellence in mentorship and was honored at SACNAS’ 2025 National Conference.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.