After the longest March, science marches on

March 2020 was the longest March. It started for me with the sweetness of budding trees and a trip to an excellent five-day workshop on cryo-electron microscopy in New York City. I was aware of concerns about aged people in faraway Italy and nagging reminders that coronaviruses don’t just cause colds, but I still juggled an impossible number of deadlines, travel plans with family, travel plans for work and the usual failed experiments, along with occasional musings on carbon footprints, political candidates and how I should read more about everything — ordinary chronic stuff for any scientist.

In its second week, March roared to a time-warping bang — a worldwide sonic boom of industry shutdowns, social isolation, school closures and pending personal and global economic collapse. We’d known that a pandemic of a virus novel to all humans was possible, but we hadn’t fathomed that it literally would play out as it does in all the bad pandemic movies.

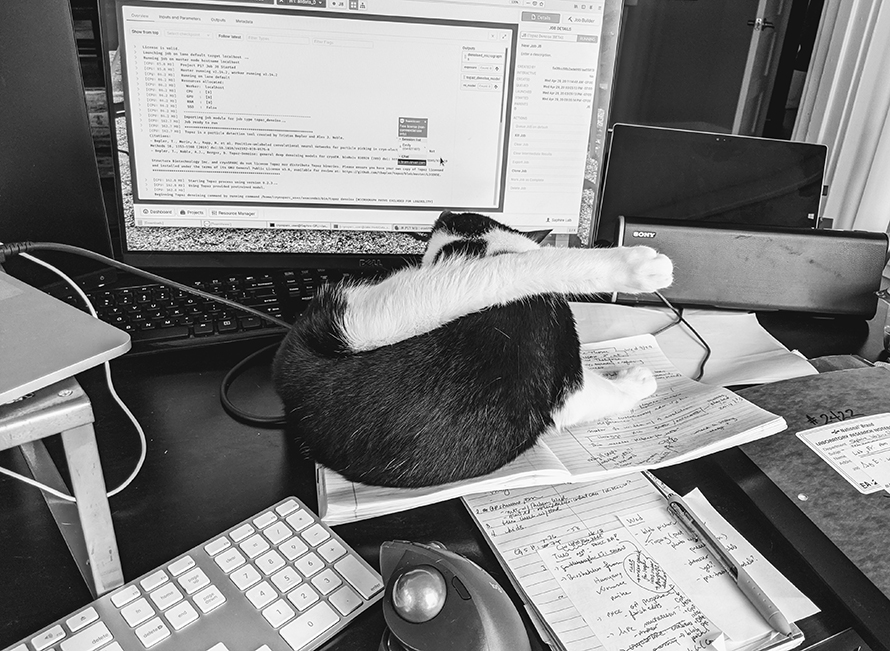

A few months later, if you still receive a salary, you probably are still working, even if you suddenly have cats and kids and enduring deadlines in an enormous makeshift pile of priorities in the middle of your living room with no practical way of sorting them all out. If you don’t still receive a salary, and some scientists now don’t, the optimism is wearing thin. The prospects of recovering lost research prowess are scary.

For anyone working on viruses, drug discovery, immune therapies and vaccines, however, the call to action now is as tremendous and conflicting as the call to stay home.

A structural virologist at home

I am a mathematician turned structural biologist who didn’t take a straightforward path to becoming a scientist. I am a postdoctoral research associate and structural virologist in the Ollmann Saphire lab at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology Division of Structural Biology and Infectious Diseases. My children are in my living room, isolated from their school and friends, and from the same living room I continue my research into structural features of immunogenic viral glycoproteins.

As virologists, my colleagues and I in the Saphire lab now enjoy an uncommon job security. For more than 15 years, our lab has been rooted in the structural biology and design of immunotherapeutics against some of the world’s most deadly viruses, including Ebola, Lassa and rabies. We are home to the Viral Hemorrhagic Fever Immunotherapeutic Consortium, or VIC, and now also to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation–sponsored CoVIC — the Coronavirus Immunotherapeutics Consortium.

And many of us are just ... home. The irony of virologists sheltering in place during a viral pandemic is unsettling. While we knew it before, we own it now: Our work on understanding viruses, viral proteins and immune responses that tackle them is of paramount importance. Whatever we manage to do now in the lab or via telework will affect how the world fares in coming years.

Fortunately, many of us are armed at home with piles of literature and piles of cryo-EM data that can all be analyzed remotely, though sometimes only with considerable effort. The literature we’re finally getting around to reading provides new insight into some of our experimental rationale, while the data analysis is critical to designing and improving therapies that target viral infectious diseases, COVID-19 included.

Distance learning

As social and physical distancing restraints have shut down in-person workshops and meetings, data processing now means learning at a distance from experts and colleagues and teaching ourselves. Teaching ourselves is not atypical in a field that’s evolving as rapidly as EM, but now the urgency to learn and apply is unprecedented.

Cryo-EM data analysis is a trying process for beginners and intermediate users alike. The researcher must navigate a multitude of possible processing workflows. The process requires remote data connections, a lot of data storage and a dozen different file extensions, and the researcher must be at ease with mathematical concepts (or with the fact that they don’t know them), individual software peculiarities, and the potential to introduce bias at multiple steps. Making the protein sample may have taken months, but getting the density map from the data and making the map into a model takes the average EM scientist anywhere from a few weeks to many, many months. The same can be said for any structural biology data, including that from X-ray diffraction, mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance.

Before COVID-19, junior scientists learning to process data often hesitated to interrupt their more experienced colleagues with questions. We wouldn’t dare contact the software or EM experts to ask for one-on-one help by email, Zoom or phone. We turned to Google, YouTube, Twitter and online bulletin boards in a valiant effort to be self-taught or to preserve confidentiality. And if our Google-fu failed us or no one had posted a solution, we returned to wallowing in the inefficiency of self-teaching. There is no time for that now; in our lab, we need to see these viral proteins and the antibodies that bind and lock them, and we need to do it ASAP. So now we Zoom, Slack and dial with abandon.

Ordinarily introverted and self-isolating, many scientists are changing our behavior, perhaps in part because our passion to help one another now trumps these personality traits, and also because virtual meetings and workshops are increasingly available.

One particular cryo-EM center, perhaps realizing that scientists don’t always reach out for the help they need, has been especially forward-thinking about distance learning. The National Center for CryoEM Access and Training, or NCCAT, in New York City is one of the National Institutes of Health Common Fund’s three cryo-EM national centers. These centers train us in the technical aspects of EM and give us access to the pinnacle of equipment. Now that the centers’ scientists are themselves at home sheltering in place, many of their microscopes are warmed, and their electron detectors are off. In addition to making past workshop course material freely available online, NCCAT now offers virtual office hours and virtual live roundtable discussions related to sample preparation, data collection, data processing and model building.

Our field of structural virology using cryo-EM is so small and so rapidly growing that this opportunity bears repeating: We are being offered free time to discuss difficult data with world-renowned experts one-on-one. This creative generosity is available because we need the knowledge and they have it — as simple as that. I hope these connections will continue and other institutions will emulate them, even when a pandemic no longer drives us.

Future Marches

A sign from the first organized March for Science on April 22, 2017, stated what scientists are now experiencing: “The oceans are rising and so are we.” In one form or another, the viral pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has swamped our psyches, our labs and our time.

We are seeing versions of scientists we never noticed before. Experts share their time and knowledge. Principal investigators allot portions of their own salaries to support research associates who otherwise would be furloughed. More researchers use and cite preprint servers to share information and credit rather than shield it. We are taking time to expand our understanding by reading outside of our fields, and we all recognize and tolerate personal struggles better because we feel them collectively. The feats of accommodation and caring go on and on.

What March 2021 will look like is anyone’s guess. From my cluttered living room corner to yours, I wish you well. I hope you can learn more broadly and more deeply. Most importantly, I hope you will, when you can, reach out to give and to ask for help.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.