What does a scientist look like?

The big idea

After taking part in hands-on STEM lab experiments as part of a youth science program I coordinate, Latino and Black students were more likely to picture scientists as people who look like them – and not stereotypical white men in lab coats.

The Young Scientists Program at the Joint Educational Project of the University of Southern California offers specialized science, technology, engineering and math instruction in local elementary schools that have mostly Latino and Black students – two groups long underrepresented in STEM fields. My colleagues and I recruit undergrad and graduate STEM majors to teach lab experiments at seven schools in Los Angeles. About 2,400 students in grades two to five receive 20 hours of instruction each year. Over 80% of the students are Latino, and about 13% are African American.

We wanted to get a sense of whether the program increases the kids' interest in science, as well as whether it changes how they view scientists. To do so, we used an evaluation tool based on the Draw-A-Scientist-Test created by educational researcher David Wade Chambers in 1983 which assessed kids' preconceived notions of what scientists look like. Researchers later developed a checklist for the drawings that includes certain characteristics like gender, age, race and being in a laboratory.

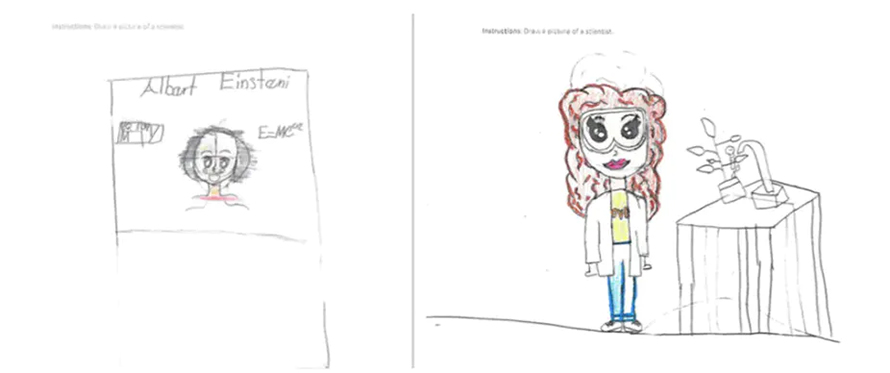

When our program began collecting drawings of scientists from its participating students in 2015, 90% of the pictures were of white men in lab coats, often looking like Albert Einstein. About 10% of the students did not know what a scientist is or does. This was demonstrated by students who wrote "I don't know" or drew question marks on their drawings.

The drawings have become more diverse over time, which we attribute to a gamut of reasons including hiring more diverse teaching staff and incorporating more examples of scientists of color into our programming.

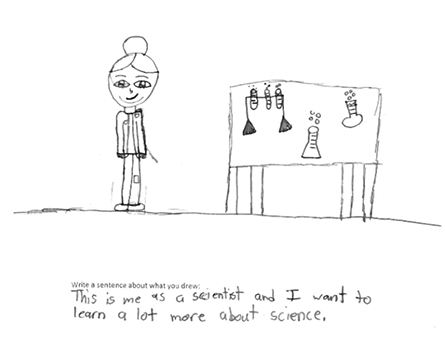

In fall of 2019, before beginning the yearlong program, we asked the kids to draw a picture of a scientist. Just under 40% drew white female scientists, 6% drew scientists of color – either men or women – and 6% drew themselves as a scientist. Almost half of them, 48%, depicted scientists as either white men or cartoon characters. After completing the program, the kids were asked to draw a picture of a scientist again. This time, 37% of them drew white women, 10% drew scientists of color and 9% drew themselves. Only 44% drew white men or cartoon characters.

These increases in students who drew themselves or scientists of color, though perhaps seemingly small, are significant. They demonstrate that the students are developing and internalizing an identity of becoming a scientist.

Why it matters

Black workers make up only 9% of the STEM workforce, and Latino workers represent 8%, though they are roughly 13% and 19% of the U.S. population, respectively. Similarly, Black and Latino undergrad and graduate students are less likely to earn STEM degrees than white and Asian students.

Without diversity in the STEM fields, it's harder for students of color to see themselves as future scientists. Research shows a more diverse scientific community would likely lead to more innovation, better health care, more supportive academic spaces and a greater trust in science, just to name a few benefits.

What still isn't known

We hope that students who finish the Young Scientists Program continue to pursue STEM and go on to become scientists themselves. However, that data is not available, and we are unable to track the graduates. We do have one former participant and four other community students who are STEM majors who are now on staff and teaching science in the community where they grew up. This epitomizes the goal of our program.

What's next

To change students' preconceived notions of scientists as being white and male, it's important they experience diverse science teachers, are taught about scientists of color in history and see diverse characters in science-related children's books. Its our hope to see more of the students in our program drawing scientists of color or themselves as scientists in future drawings.![]()

The Research Brief is a short take about interesting academic work.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.