90% of drugs fail clinical trials

It takes 10 to 15 years and around US$1 billion to develop one successful drug. Despite these significant investments in time and money, 90% of drug candidates in clinical trials fail. Whether because they don’t adequately treat the condition they’re meant to target or the side effects are too strong, many drug candidates never advance to the approval stage.

As a pharmaceutical scientist working in drug development, I have been frustrated by this high failure rate. Over the past 20 years, my lab has been investigating ways to improve this process. We believe that starting from the very early stages of development and changing how researchers select potential drug candidates could lead to better success rates and ultimately better drugs.

How does drug development work?

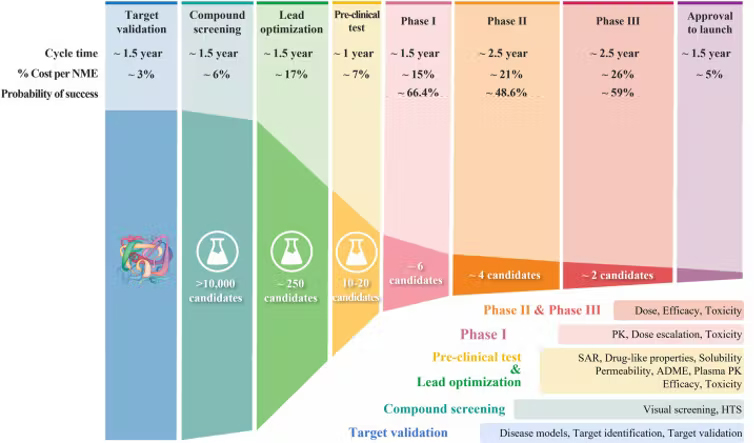

Over the past few decades, drug development has followed what’s called a classical process. Researchers start by finding a molecular target that causes disease – for instance, an overproduced protein that, if blocked, could help stop cancer cells from growing. They then screen a library of chemical compounds to find potential drug candidates that act on that target. Once they pinpoint a promising compound, researchers optimize it in the lab.

Drug optimization primarily focuses on two aspects of a drug candidate. First, it has to be able to strongly block its molecular target without affecting irrelevant ones. To optimize for potency and specificity, researchers focus on its structure-activity relationship, or how the compound’s chemical structure determines its activity in the body. Second, it has to be “druglike,” meaning able to be absorbed and transported through the blood to act on its intended target in affected organs.

Once a drug candidate meets the researcher’s optimization benchmarks, it goes on to efficacy and safety testing, first in animals, then in clinical trials with people.

Why does 90% of clinical drug development fail?

Only 1 out of 10 drug candidates successfully passes clinical trial testing and regulatory approval. A 2016 analysis identified four possible reasons for this low success rate. The researchers found between 40% and 50% of failures were due to a lack of clinical efficacy, meaning the drug wasn’t able to produce its intended effect in people. Around 30% were due to unmanageable toxicity or side effects, and 10%-15% were due to poor pharmacokinetic properties, or how well a drug is absorbed by and excreted from the body. Lastly, 10% of failures were attributed to lack of commercial interest and poor strategic planning.

This high failure rate raises the question of whether there are other aspects of drug development that are being overlooked. On the one hand, it is challenging to truly confirm whether a chosen molecular target is the best marker to screen drugs against. On the other hand, it’s possible that the current drug optimization process hasn’t been leading to the best candidates to select for further testing.

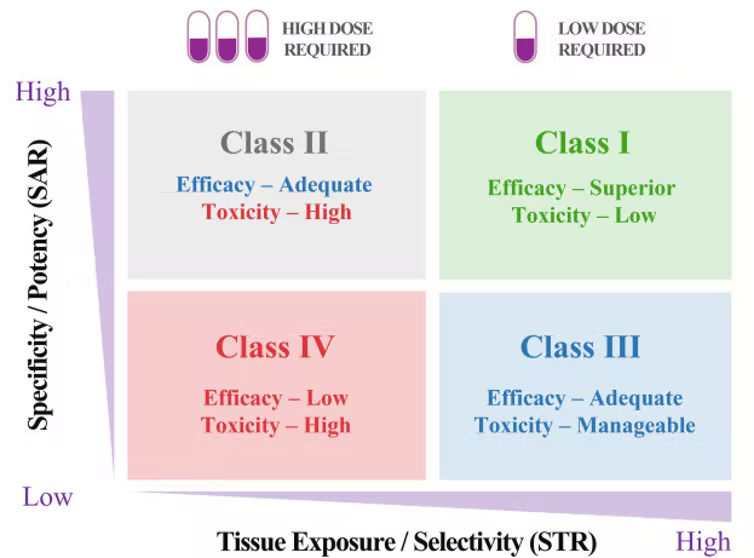

Drug candidates that reach clinical trials need to achieve a delicate balance of giving just enough drug so it has the intended effect on the body without causing harm. Optimizing a drug’s ability to pinpoint and act strongly on its intended target is clearly important in how well it’s able to strike that balance. But my research team and I believe that this aspect of drug performance has been overemphasized. Optimizing a drug’s ability to reach diseased body parts in adequate levels while avoiding healthy body parts – its tissue exposure and selectivity – is just as important.

For instance, scientists may spend many years trying to optimize the potency and specificity of drug candidates so that they affect their targets at very low concentrations. But this might be at the expense of ensuring that enough drug is reaching the right body parts and not causing harm to healthy tissue. My research team and I believe that this unbalanced drug optimization process may skew drug candidate selection and affect how it ultimately performs in clinical trials.

Improving the drug development process

Over the past few decades, scientists have developed and implemented many successful tools and improvement strategies for each step of the drug development process. These include high-throughput screening that uses robots to automate millions of tests in the lab, speeding up the process of identifying potential candidates; artificial intelligence-based drug design; new approaches to predict and test for toxicity; and more precise patient selection in clinical trials. Despite these strategies, however, the success rate still hasn’t changed by much.

My team and I believe that exploring new strategies focusing on the earliest stages of drug development when researchers are selecting potential compounds may help increase success. This could be done with new technology, like the gene editing tool CRISPR, that can more rigorously confirm the correct molecular target that causes disease and whether a drug is actually targeting it.

And it could also be done through a new STAR system my research team and I devised to help researchers better strategize how to balance the many factors that make an optimal drug. Our STAR system gives the overlooked tissue exposure and selectivity aspect of a drug equal importance to its potency and specificity. This means that a drug’s ability to reach diseased body parts at adequate levels will be optimized just as much as how precisely it’s able to affect its target. To do this, the system groups drugs into four classes based on these two aspects, along with recommended dosing. Different classes would require different optimization strategies before a drug goes on to further testing.

a role in how clinically successful a drug may be.

A Class I drug candidate, for instance, would have high potency/specificity as well as high tissue exposure/selectivity. This means it would need only a low dose to maximize its efficacy and safety and would be the most desirable candidate to move forward. A Class IV drug candidate, on the other hand, would have low potency/specificity as well as low tissue exposure/selectivity. This means it likely has inadequate efficacy and high toxicity, so further testing should be terminated.

Class II drug candidates have high specificity/potency and low tissue exposure/selectivity, which would require a high dose to achieve adequate efficacy but may have unmanageable toxicity. These candidates would require more cautious evaluation before moving forward.

Finally, Class III drug candidates have relatively low specificity/potency but high tissue exposure/selectivity, which may require a low to medium dose to achieve adequate efficacy with manageable toxicity. These candidates may have a high clinical success rate but are often overlooked.

Realistic expectations for drug development

Having a drug candidate reach the clinical trial stage is a big deal for any pharmaceutical company or academic institution developing new drugs. It’s disappointing when the years of effort and resources spent to push a drug candidate to patients so often lead to failure.

Improving the drug optimization and selection process may significantly improve success of a given candidate. Although the nature of drug development may not make reaching a 90% success rate easily achievable, we believe that even moderate improvements can significantly reduce the cost and time it takes to find a cure for many human diseases.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.