A pandemic pivot in teaching

In early 2021, Mara Livezey launched a virtual course, Chemistry in Society: How Drugs Work. Forced by the COVID-19 pandemic to move her teaching online, Livezey, an assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of Detroit Mercy, hung this class for nonmajors on a practical peg.

Her undergraduate students, she believed, could relate to the topic of drugs, licit or not. “Drugs are the easy ‘in’ for students when they’re thinking about the impact of science on society,” Livezey said.

With that as a starting point, the class would go on to explore topics from the basic biochemistry of drugs to pharmaceutical development and the action of drugs on the brain, the body and disease.

Livezey detailed these efforts — and their impact — in a 2021 study in the Journal of Chemical Education. She had already been revamping her chemistry classes before the pandemic to better serve her diverse students. COVID catalyzed her fresh approach.

Team-based learning was a hallmark of Livezey’s new chemistry course. Small groups of students met regularly to grapple with drug case studies, which included such elements as data on marijuana use and policing, trends in Adderall abuse on college campuses, and comparative costs of name-brand and generic drugs. They used such techniques as process-oriented, guided-inquiry learning, which makes groups of three to four students the focal points of the science classroom, exploring guided activities with support from the teacher.

Livezey also turned to the jigsaw method, by which the small groups become experts on a topic in the curriculum. Each student group has a day in class to present their piece of the knowledge puzzle. These techniques helped students perform better academically, as they found science more understandable and relevant to everyday life, Livezey reported. She has since adapted elements of the Chemistry in Society approach into her biochemistry classes for majors. She presented her new course design at Discover BMB, the 2023 meeting of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology,

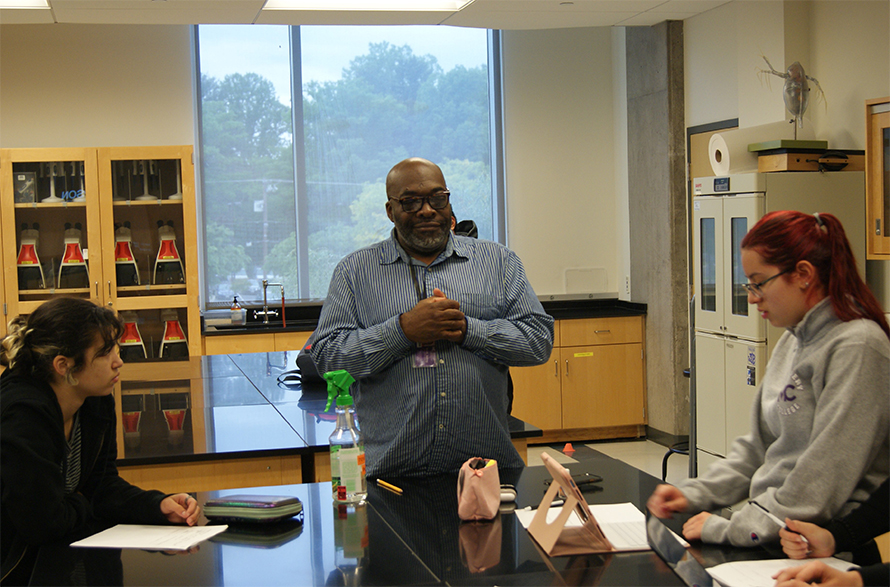

Beyond course innovations, the COVID-19 crisis also drove a fresh set of academic supports to fit a new educational context. Aubrey Smith teaches biology at Montgomery College, a two-year institution in Rockville, Maryland some of whose students move on to state universities.

During the pandemic, Smith and his colleagues used academic coaches to provide support in most biology courses. Students who had successfully finished science, technology, engineering and mathematics courses became learning assistants. They earned a stipend for holding study sessions, assisting with labs and teaching study skills.

More broadly, the public health emergency gave educators a new look at the daily challenges faced by some of their students. It was taxing to teach remotely, Smith noted, when so many students declined to turn on their cameras. Yet, as the pandemic unfolded, he came to appreciate some of the reasons why.

One biology student joined an online class from her workplace. “She was not scheduled to work that day but needed the money,” Smith wrote in an email.

“Another student of mine logged into class from her hospital bed one day after giving birth!” Smith wrote. “Teaching on Zoom gave another perspective on student resilience and determination.”

Adopting and reporting new practices

Across the field, the COVID pandemic accelerated educational innovation, as reflected in recent studies in the journal Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, or BAMBEd, edited by Phillip Ortiz.

“I think most modern faculty members recognize that instead of being the sage on the stage, we need to be the guide on the side,” Ortiz said. “We're guiding student learning but are not necessarily the only source of intelligence in the room.”

Concerns about equity may have pushed some earlier innovations, as with Livezey and Smith. Yet, the public health crisis intensified efforts to revamp the teaching of science. The pandemic made plain that virtual learning would require qualitative — as well as technical — updates in science instruction.

Kristen Procko, associate professor of instruction at the University of Texas at Austin, was the lead author of “Moving biochemistry and molecular biology courses online in times of disruption: Recommended practices and resources — a collaboration with the faculty community and ASBMB.” This editorial appeared in BAMBEd and the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Journal early in the pandemic, in April 2020. Procko also was on a team of science educators who readied resources for American Society of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology colleagues teaching through the pandemic.

From the start, Procko and her colleagues believed techniques tailored to the pandemic would endure beyond the initial crisis and enhance student experiences over the long term.

“We anticipate that, when the community returns to the classroom, they will be enticed to adopt lessons learned from remote teaching to reinvent their face-to-face teaching into more blended learning environments,” Procko wrote in the editorial.

Beyond grappling with COVID constraints, she wrote, “a secondary goal of this article is to expand the teaching toolkit of BMB educators to invigorate their teaching and actively engage students in their learning.”

For his part, Ortiz realized that virtual instruction would involve more than simply shifting the traditional biology or chemistry lecture online. Delivering education when teachers and students were apart meant redesigning the building blocks of a college science course.

“When I started teaching online after many years in a traditional classroom, I discovered that creating coursework for an online setting is not a transcriptional process, in which only the medium by which the content delivery differed, but a translational one in which I needed to use an entirely different set of tools,” Ortiz wrote in an April 2020 BAMBEd editorial.

Ortiz advocates replacing lectures with a varied set of readings, audio or video mini-lectures, open access resources and, crucially, “frequent assessments with rapid feedback.”

Daniel Dries, associate professor of chemistry at Juniata College in central Pennsylvania, thinks such innovations can do more than deliver science content to undergraduates in a crisis. COVID-friendly teaching tools have the potential to boost STEM learning for all students.

Take active learning, an educational approach in which teachers encourage students to play a major role in the classroom through planned small-group discussions, activities or presentations.

“There’s a wealth of literature that shows that active learning narrows achievement gaps,” said Dries, who studies science education.

Dries pointed to a March 2020 study in Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences of the United States of America, which makes the case for student-centered teaching. The authors of “Active learning narrows achievement gaps for underrepresented students in undergraduate science, technology, engineering, and math” sifted through test scores from 9,238 students and failure rate data from 44,606 others.

On average, active learning reduced achievement gaps in exam scores by 33% and shrunk gaps in passing rates by 45%. The percentage of time students spent on in-class activities also mattered: Classes that introduced high-intensity active learning reduced achievement gaps.

What’s more, given an engaging course design, students would learn STEM content both online and in person, as teachers across continents would show.

Transforming science education worldwide

The tidal wave of instructional change was global. Recent studies in BAMBEd and other indicators reflect the rethinking of science teaching during the pandemic from Europe to the Middle East and Asia.

Dries gave the keynote speech at a virtual symposium in July 2020, hosted by the College of Biochemists of Sri Lanka. The IUBMB and the Federation of Asian and Oceanian Biochemists and Molecular Biologists co-sponsored the event.

In “The Push We Needed: How the Global Pandemic Forced Us to Reconsider How We Deliver a BMB Curriculum,” Dries made his case for change.

“The argument was that we should have been doing a lot more in our classrooms and the pandemic freed us to shift how we can teach, assess learning and … engage and motivate our students,” Dries said.

A flipped classroom, for instance, reverses the traditional order of instruction. Instead of an in-class lecture followed by related homework, teachers deliver content via video or other online formats outside the classroom. Students then spend their class time engaged in related discussions, exercises, projects and other activities.

Keith Wheaton, an assistant professor in the biochemistry, microbiology and immunology department of the faculty of medicine at the University of Ottawa, “flipped” his fourth-year undergraduate class, “Biology of Aging,” in 2020–2021. Wheaton threw four formal lectures into a prerecorded format; then small groups of students led two workshops on molecular, cellular or evolutionary determinants of aging. Students, surveyed anonymously, reported a heavy workload but found it manageable, often looked forward to class and never mentioned Zoom fatigue, according to Wheaton’s BAMBEd study last May.

Melissa Hills, an associate professor at MacEwan University in Edmonton, Canada, championed small-group learning for science during the pandemic in a BAMBEd article that appeared in January 2023.

“Team-based learning (TBL) is useful for in-person, hybrid, or online learning and is flexible enough to accommodate pivots between these modalities,” Hills wrote. “TBL can foster classroom community and improve student satisfaction. This is especially valuable during a pandemic that has isolated students and impacted their mental health.”

In Sokota, Nigeria, researchers chronicled their virtual bioinformatics course for biochemistry majors at Usmanu Danfodiyo University. “Active and collaborative learning was encouraged due to their positive effects on learning,” Rabi’u Umar Aliyu and coauthors wrote in an April 2021 study in BAMBEd.

Despite spotty internet service and power supply, the model worked. The usual in-class lectures went online. Over 15 weeks, 15 students grappled with such tasks as analyzing a DNA sequence and pinpointing the bacteria it came from.

“Overall, the students were thrilled by the course,” the authors wrote, despite technical problems with Zoom access. What’s more, the academic results were so strong that the Sokota teaching team plans to offer virtual bioinformatics more widely at their university.

A Turkish researcher, Filiz Avci, documented how instructors at Istanbul University turned to virtual lab simulations to teach about acids and bases. In the April 2022 issue of BAMBEd, Avci wrote that the hands-on, online activities helped future science teachers master basic biochemistry.

A class of 36 fourth-year undergraduates read an article on acids and bases and discussed it in small groups via Zoom. Then students studied video simulations, crafted apt hypotheses, tested their hypotheses using their own simulations and reported on their findings. Throughout the process, the teacher furnished help as needed through Google Classroom. At the end of the course, students reported they liked and learned from their virtual lab.

Personalizing the classroom

The COVID pandemic exposed the vulnerability of instructors and students, as many struggled with illness — their own and family members’ — as well as child care or jobs. In the process, teachers became more attuned to student needs that could impact academic performance.

“We realized we could not be our best selves in our classrooms at all times, and that extended to our students,” Dries said. “Pre-pandemic, instructors were quick to criticize students as lazy, disinterested and unprepared, but I’d like to think after the pandemic, we understood that those were distractions, symptoms of other problems they carried into the classroom.”

Roderico Acevedo, an assistant professor of chemistry at Westfield State University in Massachusetts, found COVID changed the way he saw the young faces in his Zoom room.

“We, student and teacher, were all affected by the pandemic,” Acevedo said. “As teachers, we had to consider how and what our students could do and modulate our expectations.”

As a former first-generation college student, he began to pay more attention to the out-of-class demands on his own students.

“In my student career, I don’t recall my professors taking my limitations (or work schedule) into consideration when handing out assignments,” Acevedo said. “The pandemic changed that.”

At the University of Texas, Procko noticed as her faculty colleagues came to view student health problems as shared realities that required accommodation.

“Don’t come to class if you’re ill: That flexibility has endured,” Procko said. “If a person isn’t feeling well, we’ll just Zoom them in.”

COVID also seemed to shrink the emotional gulf between lecturing professors and quiet, note-taking students that already had been closing in some science classrooms. Professor Sara Brownell of Arizona State University, a neuroscientist turned educational researcher, observed that shift.

“I think the pandemic led to instructors being more accepting of mental health challenges for students and trying to be more accommodating to students,” Brownell said. “More instructors seem to be willing to talk about mental health and are considering the mental health of their students.”

As the COVID crisis built empathy, some faculty changed their style of advising. Regina Stevens–Truss, a distinguished professor of chemistry at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, suddenly had to find new ways to counsel her students.

“My authentic being walks into every class, every day, every year: I only know how to be me,” said Stevens–Truss, winner of the 2023 ASBMB Award for Exemplary Contributions to Education. “At the core of my work are community and relationships.”

The pandemic threw up barriers to both. As public health concerns rose, Kalamazoo faculty pushed their advising and office hours online. When the COVID threat subsided, the positive response from students led Stevens–Truss and some of her colleagues to retain the new approach.

“We noticed that students were more likely to attend,” she wrote in an email. “Many of us have added at least one virtual session to our classes now.”

Adapting to a virtual lab

In central Massachusetts, Acevedo and his colleagues had to update their models for laboratory coursework. They began by grappling with their own assumptions about college science.

“The pandemic made wet lab science impossible,” Acevedo said. “It made us rethink what was important about experimental science: the experimenter.”

Before COVID constraints, Acevedo and his colleagues put more of an emphasis on hands-on laboratory practice, such as using a pipette or setting up a gravity column. Faced with limits on in-person activities, the faculty turned to basic principles.

“The pandemic forced us to see things clearly: Science is about critical thinking,” Acevedo said. “So we redesigned our general chemistry course to nurture critical thinking (why controls are necessary, how to set up an experiment, and what to do when things do not turn out).”

Back at Montgomery College in Maryland, Smith is still seeing inventive use of the prerecorded lectures that were fixtures of the early COVID period.

“Since many STEM faculty members recorded their Zoom lectures, those who wanted to use the flipped classroom model implemented it when we returned to campus,” Smith wrote in an email. “Students view the prerecorded lectures, and class time is used for problem-solving and discussions.”

Educators have also found creative ways to recycle the virtual lab modules prepared during the pandemic’s early days. “The lab tutorials that were prepared for remote instruction are now used as pre-lab assignments,” Smith wrote.

Moving forward and back

After changes powered by the COVID pandemic, observers see shifts in the models of undergraduate science teaching.

“At my university, we’re moving back to the way things were: the traditional in-person classroom,” Procko said of her Austin campus.

Yet, as COVID fears subside, Procko and her colleagues are also melding old and new instruction in a way that reflects the lessons of the past several years.

“I’m going to a half-flipped model: traditional lecture one day and interactive problem-solving the next,” she said. Many of the professors she knows are now using some version of a flipped classroom, she noted.

Advocates for reforming college science do face some obstacles in changing the long-term patterns of undergraduate education. The makeup of the faculty at most institutions does not reflect the growing heterogeneity of the students.

“More recently, student demographics are becoming more diverse; however, faculty demographics have not followed suit at the same rate,” Stanley Lo wrote in an abstract for the 2023 ASBMB meeting.

Lo, a professor of cell and developmental biology at the University of California San Diego, studies science-based education; the junction of student identity, experience and learning; and faculty ideas on diversity, mentoring and teaching.

A key indicator of teaching style emerges in a teacher’s syllabus and first-day message to students. “How do you frame the work in the course: Is it a journey we’re all on together or is it us versus them?” Lo asked.

Lo studies higher education history and points to its roots as training for white, male aristocrats. He attended a U.S. Ivy League university with many legacy students whose families had been alumni. It was an uneasy fit for Lo, an Asian American immigrant from Vancouver, Canada.

“Students who come from different communities and backgrounds may have different ways of living, learning, conflict resolution, making friends,” Lo said. “We’re still not quite there where the university … belongs to all of us who come to higher education.”

Vincent Truong, an ASU sophomore who wants to become a psychologist or psychiatrist, lauds Brownell’s use of small-group discussions.

“It challenges you to explain things to others, and I think that’s the best way to solidify knowledge,” Truong said. “It’s building a moment in time, and I think we remember moments better than concepts.”

Lo views student-centered learning within the framework of recent education theories. “Working in small groups to solve problems is aligned with constructivism and social constructivism, key theories on how people learn,” he wrote in an email. “The jigsaw model in particular is powerful because it fosters interdependence while also providing opportunities for students to engage with one another in relation to course content.”

In or out of a pandemic, much evidence points to the benefits of such engaging methods of education, noted Rou-Jia Sung, an assistant professor at Carleton College in Minnesota. “Active learning is a practice that lifts all boats,” Sung said. “There’s been a few decades of data on student outcomes."

Livezey believes that student-centered pedagogy can counter the common notion that chemistry and other sciences are “unreasonably difficult and only for the smartest students.” If some in academia still are skeptical about the value of her educational approach, she has another data-based argument that could outlast COVID classroom concerns.

“Do we want to be creating the best scientists who are doing the most creative, impactful work?" Livezey said. “If the answer to that is yes, we need to make sure that scientists of all identities feel welcome in our classrooms and welcome in our fields, because we already know that diversity leads to success.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Education

Education highlights or most popular articles

Creating change in biochemistry education

Pamela Mertz will receive the ASBMB William C. Rose Award for Exemplary Contributions to Education at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Trainee mentorship as immortality

Suzanne Barbour will receive the ASBMB Sustained Leadership Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Redefining excellence to drive equity and innovation

Donita Brady will receive the ASBMB Ruth Kirschstein Award for Maximizing Access in Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

How AlphaFold transformed my classroom into a research lab

A high school science teacher reflects on how AI-integrated technologies help her students ponder realistic research questions with hands-on learning.

Writing with AI turns chaos into clarity

Associate professor shares how generative AI, used as a creative whiteboard, helps scientists refine ideas, structure complexity and sharpen clarity — transforming the messy process of discovery into compelling science writing.