Knocking out drug side effects with supercomputing

Psychedelic drugs could be effective in treating psychiatric disorders such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, but medical use of these drugs is limited by the hallucinations they cause.

"What if we could redesign drugs to keep their benefits while eliminating their unwanted side effects?" asked Ron Dror, an associate professor of computer science at Stanford University. Dror's lab is developing computer simulations using the world's most powerful and smartest supercomputer for open science, the IBM AC922 Summit supercomputer at the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility (OLCF), to help researchers do just that.

In an article published in Science, Dror's team describes discoveries that could be used to minimize or eliminate side effects in a broad class of drugs that target G protein-coupled receptors, or GPCRs. GPCRs are proteins found in all human cells. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) molecules and other psychedelics attach to GPCRs—but so do about a third of all prescription drugs, including medications for allergies, blood pressure, and pain. So important is this molecular mechanism that Stanford professor Brian Kobilka shared the 2012 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his role in discovering how GPCRs work.

When a drug molecule attaches to a GPCR, it can cause multiple simultaneous changes in the cell. Some of these changes might contribute to a drug's beneficial effects, but others can lead to less-than-desirable or even dangerous effects.

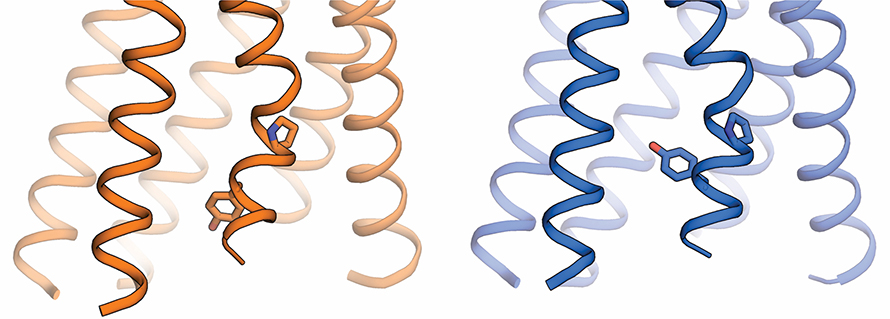

Using the OLCF's Summit and a computing cluster at Stanford, the team compared computer simulations of a GPCR with different molecules attached. Dror's team was then able to pinpoint how a drug molecule can alter the way a GPCR's atoms are ordered. Changing the protein's atomic arrangement affects the protein shape and can allow a drug molecule to deliver beneficial effects without side effects—something that has remained mysterious until now. Based on these results, the researchers designed new molecules that were shown computationally to cause beneficial changes in cells without unwanted changes. Although these designed molecules are not yet suitable for use as drugs in humans, they represent a crucial first step toward developing side-effect-free drugs.

Today, researchers typically test millions of drug candidates—first in test tubes, then in animals, and finally in humans—hoping to find a "magic" molecule that is both effective and safe, meaning that any side effects are tolerable. This massive undertaking typically takes many years and costs billions of dollars, and the resulting drug often still has some frustrating side effects.

The discoveries by Dror's team promise to allow researchers to bypass much of that trial-and-error work so that they can bring promising drug candidates into animal and human trials faster and with a greater likelihood of success.

Stanford postdoctoral scholar Carl-Mikael Suomivuori and former graduate student Naomi Latorraca led an 11-member team that included Robert Lefkowitz of Duke University, with whom Kobilka shared the Nobel Prize, and Andrew Kruse of Harvard University, Kobilka's former student.

"In addition to revealing how a drug molecule could cause a GPCR to trigger only beneficial effects, we've used these findings to design molecules with desired physiological properties, which is something that many labs have been trying to do for a long time," Dror said. "Armed with our results, researchers can begin to imagine new and better ways to design drugs that retain their effectiveness while posing fewer dangers."

Dror hopes that such research will eventually eliminate the dangerous side effects of drugs used to treat a wide variety of diseases, including heart conditions, psychiatric disorders, and chronic pain.

The team's simulations were performed under a computing allocation in the Innovative and Novel Computational Impact on Theory and Experiment program at the OLCF, a US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility located at DOE's Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

This story was written by Tom Abate at Stanford University and adapted by Rachel Marisa Harken at Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Missing lipid shrinks heart and lowers exercise capacity

Researchers uncovered the essential role of PLAAT1 in maintaining heart cardiolipin, mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, linking this enzyme to exercise capacity and potential cardiovascular disease pathways.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.