JLR: Cascading errors

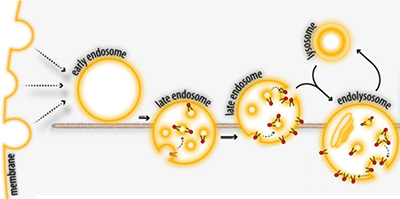

After endocytosis, membrane-spanning proteins or lipids that become part of an endosomal vesicle can face into the lumen of the late endosome and the lysosome. This makes parts of the molecule that were once on the cell surface accessible to enzymes in the lysosome.Adapted from Pribasnig et al./JBC 2015

After endocytosis, membrane-spanning proteins or lipids that become part of an endosomal vesicle can face into the lumen of the late endosome and the lysosome. This makes parts of the molecule that were once on the cell surface accessible to enzymes in the lysosome.Adapted from Pribasnig et al./JBC 2015

Lysosomal storage disorders are genetic diseases. When any one of a number of enzymes in the lysosome loses its function, the molecule it breaks down accumulates, slowly building to levels that are toxic to cells. An article in the Journal of Lipid Research gives a clue as to why complex lipids known as gangliosides accumulate even in lysosomal storage disorders that don’t affect ganglioside metabolism directly. The work was led by Konrad Sandhoff, who discovered a lysosomal storage disorder (since named after him) in 1968.

The ganglioside GM2 is found mostly in the outer plasma membranes of cells in the nervous system. In Sandhoff disease, which is caused by mutation of the enzyme that cleaves the complex sugar in GM2’s head group, GM2 quickly accumulates in patients’ neuronal lysosomes. This accumulation can be neurologically debilitating and is often fatal.

After undergoing endocytosis as part of normal membrane turnover, GM2 becomes part of the surface of a vesicle in the lysosome (see figure). The enzyme that breaks down GM2, which resides in the lysosomal lumen, depends on binding between GM2 and an accessory protein called GM2AP to find and break down its substrate. Until now, researchers didn’t know whether GM2AP recruits the enzyme to the vesicle surface or delivers the lipid to the enzyme in solution.

Using surface plasmon resonance, scientists in Sandhoff’s lab led by postdoctoral fellow Susi Anheuser showed that GM2AP extracts gangliosides from the membrane of intraluminal vesicles. They also showed that GM2AP activity depends on the lipid makeup of those vesicles. If the vesicle has a negative surface charge, as is typical in healthy cells, GM2AP can extract gangliosides and ferry them to the relevant enzyme. If the quantity of neutral or positively charged lipids increases, the researchers observed, then that extraction is less effective, and ganglioside breakdown slows.

“GM2 degradation activity is regulated by molecules in the microenvironment of the reaction,” Sandhoff explained. “If the lipids are changed, you change everything.”

In addition to building up in some disorders as the main storage product, gangliosides can accumulate in disorders that primarily affect other lipids, such as cholesterol or mucopolysaccharides. Before now, scientists couldn’t explain why that secondary buildup occurred. This paper suggests that raising the concentration of these other lipids in the lysosomal vesicle disrupts ganglioside degradation by affecting the interaction between GM2AP and the vesicle surface.

Richard Proia was not involved with this JLR paper, but he studies sphingolipids at the National Institutes of Health. “Normally, simple-mindedly, you think of each enzyme carrying out a single reaction and working by itself,” he said, adding that this work complicates that view. “If one lipid is stored, and that has a negative effect on some other pathway, then the other pathways are now going to store lipids. That explains a phenomenon that’s been known for a long time.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.