Finding neoantigens faster — advances in the study of the immunopeptidome

The immune system may seem quiescent until an infection prods it to leap into action. In fact, it maintains active surveillance to distinguish what belongs in the body from what does not. As part of this surveillance, T cells prowl through tissues, seeking signs of something amiss. Special constitutively active mechanisms report to T cells on cell contents that otherwise would be hidden.

David Gfeller leads the computational cancer biology group at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, where his lab works to characterize immune infiltrations at the cell level. “In order to detect cells that are infected or malignant, something intracellular has to be presented at the cell surface,” Gfeller said.

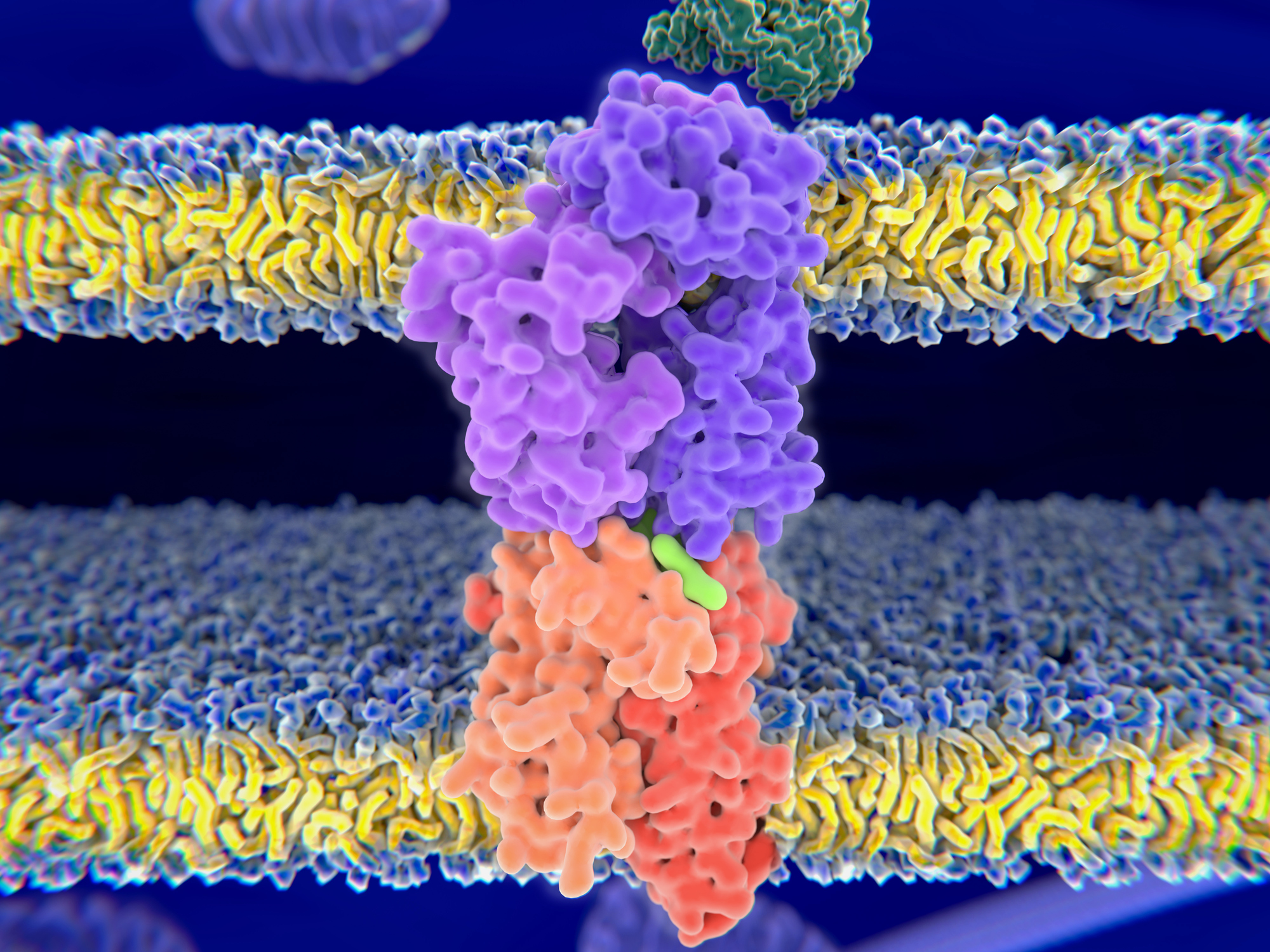

That presentation is the job of human leukocyte antigens, or HLAs, a subset of which display peptides pulled from chopped-up intracellular proteins. The repertoire of peptides they present, which varies according to HLA alleles, protein expression patterns across tissues and other factors, is called the immunopeptidome; it determines what antigens T cells can recognize and respond to.

Understanding how peptides are selected to become part of the immunopeptidome is key to harnessing adaptive immunity. For example, an effective vaccine must use a peptide that HLA proteins will take up and display. When antigen presentation goes amiss — if T cells mistakenly recognize ordinary components of the cell as dangerous invaders or overlook new mutant antigens — diseases like autoimmunity and cancer can result.

Two papers in Molecular & Cellular Proteomics highlight recent advances in the study of the immunopeptidome.

Excitement over immunopeptidomics

The first tumor-specific HLA-binding peptide was identified in 1997. But immunopeptidomics really took off in 2014, when researchers discovered that cancer treatments to boost T cell activity, overcoming immunosuppression induced by tumors, depend on T cell recognition of tumor-specific antigens. Predicting the composition of the immunopeptidome and how it differs between healthy and cancerous tissue became part of a medical frontier with enormous potential: cancer immunotherapy.

Such is the history reviewed by Juan Antonio Vizcaíno, a proteomics team leader at the European Bioinformatics Institute, and colleagues in a perspective in MCP. The authors summarize technical advances in immmunopeptidomics and findings that have linked HLA alleles with human diseases. They also look ahead to a time when immunopeptidome-wide association studies may make it possible to predict an individual’s susceptibility to autoimmunity, infection or cancer — and they discuss the possible challenges in the way.

Immunopeptidomics experiments remain technically challenging. Several fieldwide initiatives aim to pool data on the peptides presented by HLA proteins in various tissues and disease states, among them the Immune Epitope Database and the Human Immuno-Peptidome Project. Based on this hard-won knowledge about the binding preferences of HLA proteins, researchers have generated algorithms to predict which peptides HLA proteins may display, enabling computational study of the immunopeptidome. But these algorithms still fall short in predicting display of post-translationally modified peptides.

Phosphorylated immunopeptides

In addition to genetic changes, many cancers undergo major changes to signaling pathways — for example, 46% of cancer samples in a recent study carried alterations in the MAP kinase pathway. Quantifying how those signaling changes might be reflected at the cell surface is a matter of conjecture.

Michal Bassani–Sternberg, an investigator at the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research in Lausanne, studies cancer-specific HLA ligands. “We cannot yet extract or purify phosphorylated HLA-binding peptides to a really good depth of coverage as opposed to the depth of unmodified peptides,” she said.

Until recently, this technical limitation hampered efforts to understand whether unusual phosphopeptides might be unique tumor markers in some cases of cancer.

Now, doctoral student Marthe Solleder and collaborators in Bassani–Sternberg’s and Gfeller’s labs have come up with a new bioinformatics tool for predicting phosphorylated HLA ligand peptides. They report the work in MCP.

“We collected a huge data set of peptides displayed at the cell surface that were measured by mass spectrometry,” Bassani–Sternberg said, “and we searched the spectra for modified peptides that contain a phosphate group.”

Working mostly with previously collected spectra from immunopeptidomics experiments, the team reanalyzed immunopeptidome data, uncovering phosphorylated HLA-binding peptides that previously had been overlooked. This let them make inferences about HLA proteins’ phosphopeptide binding preferences.

“For example, of the three types of HLA class I molecules, one called HLA-C is especially apt to bind to phosphorylated peptides,” Solleder said.

The algorithm may be useful for expanding the known range of targets displayed on cancer cells. Bassani–Sternberg said, “If we know where the mutations are in the genome of a patient, we can apply these prediction algorithms to predict which of the mutations is likely to be presented as a ligand on the HLAs of the patient. Similarly, we can now predict which of the known phosphorylated sites the proteins are likely to be presented as HLA ligands.”

The researchers have shared all their data and computational tools. They hope the extra information about phosphorylated peptides may help others find novel antigens. In the long term, such insights may help guide tumor-targeting treatments.

To learn more about how antigen presentation works, watch this illustrated tutorial.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.