Put a smile around your neck

For Raven Hanna, the motivation to launch a science-themed jewelry company came from a dark place.

While coping with an “emotionally exhausting” relationship breakup, Hanna, a molecular biophysicist by training, was browsing sleepily through a book on neurotransmitters, trying to understand the science behind her emotional state. She stumbled upon a passage on serotonin. Hanna, who describes the molecule as being “symbolic of happiness,” had an epiphany: This molecule “would make a pretty necklace,” she recalls thinking.

Raven Hanna Images courtesy of Raven Hanna

Raven Hanna Images courtesy of Raven Hanna

When an Internet search for such an item came up empty, Hanna took matters into her own hands, enlisting a local jeweler to make a silver sterling pendant in the shape of serotonin.

Inspired by that experience, in the mid-2000s, Hanna launched her one-woman science-themed jewelry company, Made With Molecules. Blending her scientific background with her natural creativity, Hanna produces pieces for people who, like her during that painful period, are looking for physical representations of their feelings. “People see their molecules as a personal symbol,” she says.

Strangely enough, jewelry never appealed to Hanna growing up. “I have not had a huge interest in jewelry until I started this,” she says. Instead, she was a dedicated scientist, first getting her Ph.D. from Yale University in 2000 and then completing a postdoctoral stint at the University of California, Berkeley. But she was getting restless in the lab. “It was around the end of my postdoc that I was thinking more about how to communicate science to people who don’t realize that science is really cool,” says Hanna, who decided to act on her newfound interest by enrolling in a science writing program at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Hanna still wasn’t sure about where her passions would take her career until she was approached in a Gap store by a teenager who inquired about her serotonin necklace. “I suddenly found myself giving a science lesson,” she says. That interaction crystallized for Hanna the realization that “I really wanted to communicate science through art.”

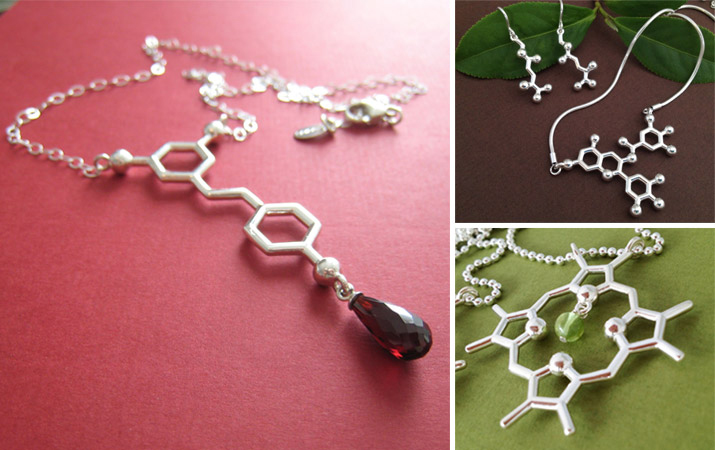

Examples of Hanna's designs

Examples of Hanna's designs

Hanna chooses her designs carefully, focusing on molecules that could be “really interesting and also could be pretty as jewelry,” she explains. Examples include a neurotransmitter bracelet, a chlorophyll/heme necklace that incorporates semiprecious stones and nucleotide earrings. Ever the scientist, Hanna includes a small card with each of the 5,000 pieces of jewelry that she produces annually to help explain the underlying chemistry and functionality of the molecule.

Hanna says she makes sure that the pieces retain their scientific accuracy, admitting that she is constantly asking herself, “Have I watered down the science behind the jewelry too much?” Ensuring that her work appeals to both scientists and nonscientists is important to Hanna. “I really wanted my stuff to be aesthetic enough to appeal to people who aren’t necessarily attracted to the very geeky science stuff,” she says.

Of course, those who are attracted to the geeky science stuff make up a significant proportion of Hanna’s customer base. Her first major showing at an American Chemical Society meeting was an enormous hit. “It was so amazing to me that people really love the stuff they work on, to the point where it’s not work. Their chemical is a member of the family,” she says. After that meeting, Hanna was inundated with requests from scientists asking her to make “whatever their favorite molecule was.”

The most challenging part of being a professional jeweler, she says, has been adjusting to the business side of things, such as having to learn how to file taxes as a business owner. The creative aspect of her business, however, comes naturally. “I have to say that a lot of skills that I use doing this are things that I’ve enjoyed doing my whole life,” she says. “When I was doing science, I felt there was a huge value on creativity that was respected and honored.” Hanna says a “love of experimentation and the willingness to observe results in an objective way” are, in her view, critical aspects of both artistry and science.

As for jettisoning her life at the bench in favor of one in the studio, Hanna admits having certain regrets. “I miss growing bacteria so much,” she says with a laugh. However, the repetitive nature of scientific experimentation and validation was not for her. “At that point, it’s not fun anymore,” she says. “It’s work.” While Hanna is comfortable with her choice, she occasionally runs into people who wonder, “What does my mother think about how I’m not doing science anymore?” she says.

Thankfully, Hanna, who is now living in Hawaii, knows that her current career is making an impact. She says her customers are “looking for symbols in their life and none of the traditional symbols really appeal to them.” It therefore shouldn’t be surprising that they would turn to a nontraditionalist like Hanna to help them express themselves. That serotonin necklace around her neck is now more appropriate than ever.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

In memoriam: Walter A. Shaw

He is the namesake for the Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research and founded Avanti Polar Lipids.

Dorn named assistant professor

She will open her lab at the University of Vermont in fall 2026, and her research will focus on catalysis, synthetic methodology and medicinal chemistry.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Kiessling wins glycobiology award

She was honored by the Society for Glycobiology for her work on protein–glycan interactions.

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.