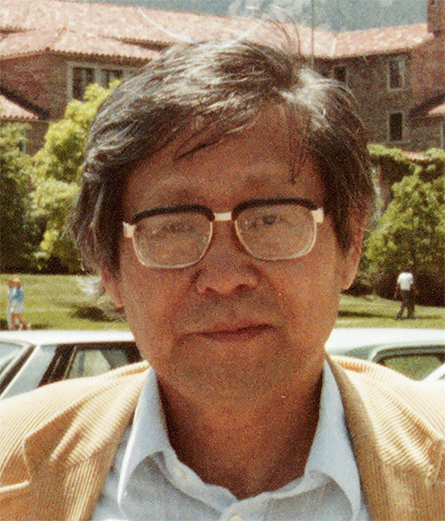

Noboru Sueoka (1929 – 2021)

Noboru Sueoka died May 14. He was an early and active contributor to studies aimed at understanding the genetic code; the role of tRNA; development of a method of fractionating tRNA (together with his wife, Tamiko Kano–Sueoka); the variation in base composition and evolution of DNA sequences; and the mapping of bacteria genes. He made widely known contributions to our understanding of DNA replication. Indeed, he coined the term “origin of replication.” Using specific gene-transformation ratios and enlightened math, Sueoka showed that Bacillus subtilis cultures in exponential growth duplicate their chromosomes with replication forks traveling with the same velocity, all starting from the same chromosome origin. Using Chlamydomonas, he also found out that during meiosis two rounds of replication are all semiconservative.

Sueoka was born April 12, 1929, in Kyoto, Japan, the son of Masashin and Ayako (Nishida) Sueoka. By middle school, he had his mind set on becoming a geneticist, influenced by his uncle, a plant geneticist. In grade school, he often was lost in thought and was punished for not paying attention. This trait persisted for the rest of his life and enabled him to think outside of the box.

After receiving B.S. and M.S. degrees from Kyoto University, Sueko earned his Ph.D. from the California Institute of Technology. As a postdoc at Harvard, with three advisors, James Watson, Paul Doty and Paul Levine, he discovered the correlation between guanine-cytosine content and cesium-chloride density and immediately used this finding to discover the first satellite DNA, the nearly pure adenine and thymine sequences from crab.

As a lab head for two years at the University of Illinois and then for 10 years at Princeton, he carried out seminal studies on bacterial chromosome replication in the spore-forming bacteria Bacillus subtilis.This creature had two convenient properties. First, it could be genetically transformed with pure DNA — rare in those days. Better, its spores contained DNA without replication forks; when the spores germinated, the chromosomes replicated synchronously, starting from the same location on all chromosomes. Sueoka, with co-workers, verified this synchronous replication using ratios of gene-transformation efficacies (they doubled, in a fixed order, starting with ade6 at the origin, as the chromosome fork passed the loci). During rapid growth conditions, the chromosomes replicated, in his words, “dichotomously, with each branch behind the first fork having daughter forks.” Finally, his lab showed that the replication origin stayed permanently attached to the membrane throughout the cell cycle.

Building on his continuing work on prokaryotic models, Sueoka aimed at understanding how the nervous system, particularly the mammalian brain, achieved its complex wiring and function. His approach was twofold. First, it was cell oriented; brain tumors were induced, and cells from those tumors were selected for neuronal and glial characteristics, one line of which, RT4, had stem cell properties and could differentiate to either, leading to the discovery of markers and cell-fate switch mechanisms. Second, he examined overall gene expression in these cell lines and in whole organs. This led to one of the first estimates of the number of genes in mammals and insight into the role of polyadenylation of messages.

Over his 50-year career, Sueoka was known for his unfailing kindness, gentleness, openness and sincere dedication to his colleagues, postdocs, technicians, and graduate and undergraduate students. He was an exceptional mentor. He and his wife, known as Tami, provided a pleasant laboratory environment where everyone felt safe and understood. He encouraged members of their team to work hard, succeed in their projects and, most importantly, be happy and enjoy life. He was always ready to talk to students about their projects and valued their input. He encouraged students to think independently and made them feel their ideas were valued. One could ask him any question (or complain to him), and he would consider it seriously. He was a fundamentally curious person and had deep interest in understanding other cultures.

Sueoka shared his wisdom and observations of the human experience and what it meant to be a scientist. He distinguished between two approaches to science research: a riskier approach that aims to discover fundamental and novel processes, and a less risky path that aims to nail down the details of these previously discovered processes. He chose and valued the former approach.

One of the earliest Japanese scientists to study and have a career abroad, Sueoka’s scientific courage and personal independence helped transform Japanese biology from a feudal and technique-oriented discipline after World War II to its current position in the first rank of scientific cultures. He was not a pushy person; he did this by his pioneering example and by directly encouraging independence and initiative in others.

In addition to his seminal contributions to molecular biology, Sueoka will be remembered as an enthusiastic skier, mushroom hunter and trout fisherman, passing on his love for these activities to his students and postdocs. He will be missed by his many postdocs and graduate and undergraduate students. In particular, we both cherish our time in his lab. He will be especially missed by his wife and research partner, Tami, and by their daughter, Miki Sueoka.

Sueoka was an assistant professor in the microbiology department at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign from 1960 to 1962. His career led him to Princeton University, where he was an associate professor from 1962 to 1965, a professor from 1965 to 1969, and held an endowed professorship from 1969 to 1972, all in the biology department. He moved to the newly created molecular, cellular and developmental biology department at the University of Colorado, Boulder, where he was a professor from 1972 to 1997. He then served as an adjunct professor at the University of California, Irvine, from 1997 to 2002.

Sueoka was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and a Guggenheim fellow. He received a Waksman Award from the Theobald Smith Society and a fellowship from the Japanese Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Simcox wins SACNAS mentorship award

She was recognized for her sustained excellence in mentorship and was honored at SACNAS’ 2025 National Conference.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Thiam elected to EMBO

He was recognized during the EMBO Members’ Meeting in Heidelberg, Germany, in October.