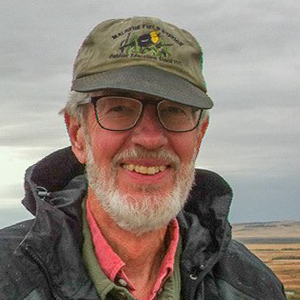

Kensal E. van Holde (1928 – 2019)

Kensal van Holde, one of the world’s premier physical biochemists and a longtime associate editor of the Journal of Biological Chemistry, died peacefully at home on Nov. 11 following a brief illness. He was 91.

and the Nucleus: The Work of Kensal E. van Holde, ” in the Journal

of Biological Chemistry.

Perhaps the best way to appreciate Ken’s scientific career is to read his own words. In a 2008 Reflections article in JBC, he describes a scientific odyssey that began in the 1950s with a focus on the ultracentrifuge. Together with Robert “Buzz” Baldwin at the University of Wisconsin, he developed a method for rapid approach to sedimentation equilibrium and its use to analyze the size and shape of protein molecules. This led to a faculty position in the department of chemistry at the University of Illinois, where he designed improvements in light scattering and circular dichroism, as well as ultracentrifugation. He continued to explore protein structure and function, with emphasis on invertebrate respiratory proteins.

As Ken’s interests evolved, he sought an environment where he could focus his biophysical strengths on problems in biology. In 1967, he moved his laboratory to Oregon State University, joining the newly formed department of biochemistry and biophysics. There he met Irvin Isenberg, who introduced him to chromatin.

Irv and Ken noted that four of the five histones in chromatin were present in equimolar quantities. The prevailing view was that histones somehow coated fibers of supercoiled DNA. Measurements of electric dichroism of calf thymus chromatin carried out in Ken’s lab by Randy Rill ruled that out but didn’t solve the structure.

Randy and Ken turned to the ultracentrifuge. Limited digestion of chromatin with micrococcal nuclease yielded a preparation containing both DNA and the core histones, which displayed a ladder when analyzed in the ultracentrifuge or by gel electrophoresis. Analysis by precipitation and resolubilization suggested that the DNA in chromatin was present in two forms, one of which was particulate. Physical analysis of the particulate fraction indicated that DNA was on the outside of the particle, in disagreement with the prevailing model. Chintamin Sahasrabuddhe and others analyzed these particles, showing them to be spherical, with the DNA wrapped around the outside.

Ken’s laboratory had described the nucleosome core particle. Others took notice, and Ken’s group was then in a race to define chromatin that continued until 1997, when X-ray crystallography confirmed the van Holde model.

I met Ken in 1977, when I was a candidate for the chairmanship of his department at OSU. Ken had recently been awarded an American Cancer Society research professorship, and this relieved him of all departmental duties. I asked how he wanted to contribute, and he said he would maintain a full teaching load (three courses per year) so long as I promised not to put him on any committees. To say that I was delighted would be an understatement. I didn’t realize at that embryonic stage of our relationship that Ken was as devoted to teaching as to research. In the summers, he regularly decamped to Massachusetts, where he taught and served as instructor-in-chief of the famed physiology course of the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole.

I learned more about Ken’s devotion to teaching when he suggested that we teach a course together. We called the course DNA-Protein Interactions and graded each student not by exams but by preparation of an original research proposal — just like the National Institutes of Health, but we assigned grades, not priority scores. Ken was a spellbinding lecturer, and I learned a great deal during the several times that we taught the course together.

Members of Ken’s research group were devoted to him to a greater extent than I have seen with other professors. They worshipped him. Their unusual esprit de corps was evident on Friday afternoons. Ken’s laboratory included a small room in the building’s inner core dubbed the Cave. There, members of his group and others gathered to drink beer and talk science. As department chair, I had to tell them liquor was forbidden on campus and that the Cave would close if anyone complained. Eventually, someone complained, and the OSU president visited my office to admonish me for permitting Cave parties even though they were the occasions for some excellent science.

Ken was a gifted writer as was shown in his two research monographs, “Chromatin” and “Oxygen and the Evolution of Life” as well as in “Principles of Physical Biochemistry,” co-authored in the second edition with Shing Ho and Curtis Johnson. I should not have been surprised at Ken’s excitement when I approached him about co-authoring a general biochemistry textbook. By the time we had written a prospectus, outline and two sample chapters (one each), I feared this was a bigger job than we could handle. However, in a phone call between Corvallis and Stockholm, where I was on sabbatical, Ken’s enthusiasm was palpable. We pushed ahead, and “Biochemistry” was published in four editions, sometimes with co-authors, in a competitive market.

After his formal retirement in 1993, Ken continued to write books—now with his former associate, Jordanka Zlatanova. In 2015, they published “Molecular Biology,” a textbook, and in 2018, barely a year before Ken’s death, “The Evolution of Molecular Biology,” a historical account. Both books display Ken’s biophysical expertise and his gift for clear writing.

Ken enjoyed a rich family life. With his wife Barbara and their four children, he shuttled between Corvallis, Woods Hole and their mountain retreat in the Oregon Cascades. Some years after Barb’s death in 2010, Ken reconnected with a widowed OSU faculty wife, Myrna Shepper, and they were married in 2015.

In recognition of his work, Ken was elected to the National Academy of Science in 1989 and to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1996.

Memorial services

Interested parties are welcome to attend celebrations of Ken Van Holde’s life:

- On the West Coast, 1-5 p.m., Feb. 29, at the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship in Corvallis, Oregon

- On the East Coast, 4-9 p.m., July 23, at the MBL Club in Woods Hole, Massachusetts

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Kiessling wins glycobiology award

She was honored by the Society for Glycobiology for her work on protein–glycan interactions.

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.

Simcox wins SACNAS mentorship award

She was recognized for her sustained excellence in mentorship and was honored at SACNAS’ 2025 National Conference.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.