A battered island rises

More than 100 days ago, Hurricane Maria tore across Puerto Rico with 113 mph wind gusts, torrential downpours and flash flooding. In the storm’s immediate aftermath, island residents found themselves without electricity and running water. Help from the mainland United States came slowly. After an initial humanitarian crisis and now on a grinding road to recovery, the people of Puerto Rico have come together in ingenious and innovative ways — fetching groceries on farm tractors and holding university lectures in tents.

The situation has improved somewhat in the last two months; as of December, 93 percent of the island had access to boil-advisory water, 73 percent of cell tower sites were running and 66 percent of electrical power on the island had been restored. Among the efforts of a host of nonprofit organizations, the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology awarded $76,000 in grants to 52 scientists in Puerto Rico to help mitigate the damage to their laboratories and lives across the island.

Ruined buildings are seen from a U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Air and Marine Operations, Black Hawk helicopter during a flyover of Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria, Sept. 23, 2017. courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/U.S. Customs and Border Protection/photo by Kris Grogan

Ruined buildings are seen from a U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Air and Marine Operations, Black Hawk helicopter during a flyover of Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria, Sept. 23, 2017. courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/U.S. Customs and Border Protection/photo by Kris Grogan

Lost with the freezers

José A. Rodríguez—Martínez

José A. Rodríguez—Martínez

José A. Rodríguez—Martínez, an assistant professor of biology who started his lab at the University of Puerto Rico-Río Piedras in 2017, lost all his frozen supplies when the building’s backup generators failed to start, leaving the lab without power for four days.

“All of my freezers lost temperature, so I lost everything — all my molecular biology reagents, all my enzymes, all my PCR master mixes,” he said. “The week before Maria, we successfully purified our first protein … then Maria came and took it away.”

The protein that Rodríguez—Martínez’s lab had purified was a transcription factor, OPTIX, that is linked to the rise of red color patterns on the wings of Heliconius butterflies. Despite these setbacks, Rodríguez—Martínez’s lab, which examines the DNA binding preferences of transcription factors, sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins, got back on track in the final months of 2017.

While electricity returned to his lab within days via the backup generators, it took weeks to come back to other parts of the university and the surrounding areas of San Juan. Rodríguez—Martínez, who lives close to the campus, had to wait nearly two months for his power at home to return.

Many trees were uprooted by Hurricane Maria’s strong winds. courtesy of HECTOR JIRAU

Many trees were uprooted by Hurricane Maria’s strong winds. courtesy of HECTOR JIRAU

“We had to figure out where to get ice,” he said. “I was freezing my water bottles in the minus-80-degree freezer that survived … Since it was completely empty and clean since I lost everything, it was perfect.”

Research in Rodríguez—Martínez’s lab picked back up by late November. “(We are) moving basically at the same pace, we just have to redo a lot of things,” he said. “I was super lucky … a big portion of my reagents were from New England Biolabs and Promega, and both of them replaced my entire purchases.” Rodríguez-Martínez plans to use his ASBMB grant to cover the remaining reagents that were lost in the downed freezers.

“I think a main concern now is getting electricity back to people,” he said. “The government is reporting mostly on the percentage of electricity generated, (but) they don’t report the number of customers or households, the percentage of households … people are desperate to get power, mostly outside of the metropolitan area.”

Flooding and faltering

In addition to widespread electrical outages, many labs flooded after roofs were damaged by Maria’s heavy winds.

Hector Jirau

Hector Jirau

Hector Jirau works in the laboratory of the environmental toxicologist Braulio D. Jiménez and currently is investigating the effects of particulate matter on asthma and other respiratory diseases. Jiménez’s lab is on the second floor of the 10-story Guillermo Arbona Building at the university’s medical center. When the hurricane’s winds damaged the building’s roof, the upper floors flooded and water leaked down to the second floor.

“When I went to the lab, it was flooded, and most of our instruments were gone,” Jirau said. “We have a cell culture room which pretty much doesn’t work right now.”

The computer that contains data for Jirau’s thesis also was damaged; he hopes his ASBMB grant will cover the repair.

“Right now I have no access to my computer,” he said. “I need to at least save the hard drive and extract all my data (for) my thesis project.”

Many students working in storm-damaged labs, including Jirau, are moving to labs at mainland U.S. institutions, including Harvard University and Brown University, where they can continue their research alongside experts in their fields. The nonprofit Ciencia Puerto Rico, which aggregates and disseminates sources of scientific aid available to Puerto Rican researchers, shared information about this opportunity and many others, including grants from the ASBMB, the American Association for the Advancement of Science and similar associations.

“I’m talking with a professor from Harvard School of Public Health, and we’re trying to collaborate so I can go see the campus and continue my thesis over there,” Jirau said.

Jorge Martinez

Jorge Martinez

Public transportation was also shut down in San Juan, according to Jorge Martinez, another graduate student in Jiménez’s lab. Martinez lost a number of reagents to the downed freezers, and his car broke down in the aftermath of the hurricane; he plans to cover the cost of a transmission repair and some of the lost reagents with his ASBMB grant.

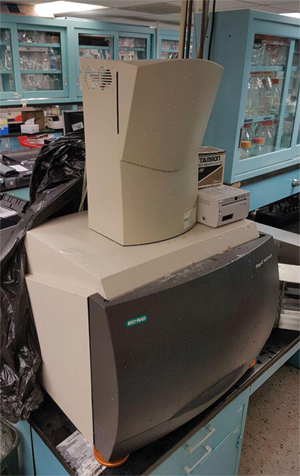

A Bio-Rad multi-imaging machine in Braulio D. Jiménez’s lab, used to capture images of various types of fluorescent samples, was damaged beyond repair by flooding. courtesy of HECTOR JIRAU

A Bio-Rad multi-imaging machine in Braulio D. Jiménez’s lab, used to capture images of various types of fluorescent samples, was damaged beyond repair by flooding. courtesy of HECTOR JIRAU

Martinez lives in San Juan on the northern coast, but he rode out the hurricane with his family at their home in the middle of the island. “The day after Maria, we tried to visit some family members that were close by, but it was a bit too much and it broke the transmission of the car,” he said. “We had to go over trees, over debris, over boulders — it’s a four-wheel-drive car, but it can’t do magic.”

Between his vehicle’s broken transmission and the shutdown of public transportation in San Juan, Martinez had to carpool both to the lab and to his work auditing biomedical studies at the Fundación de Investigación, a part-time job he took to help his family make ends meet while the hurricane recovery is under way.

“Puerto Rico has always been an island where every Puerto Rican matters for every other Puerto Rican,” Martinez said. Many residents near the center of the island are farmers, he said, and some of them used their tractors and similar equipment to get supplies to people who were stranded. “They improvised transportation methods from one side of the broken bridge to the other to at least send food to those that couldn’t access any supermarkets.”

Beyond San Juan

Jirau weathered Maria with his family in the mid-island municipality of Utuado. “The center of the island was hit pretty hard,” Jirau said. “In Utuado, every 10 or 15 kilometers or so, you will see a lot of houses without roofs. You could actually see a lot of people living outside or having tents nearby their houses.”

Keisy Bonano

Keisy Bonano

The recovery efforts appear to be moving more slowly outside the capital and surrounding metropolitan area. Forty-five minutes to the southeast of San Juan, Puerto Ricans in the municipality of Cayey still lacked basic amenities in early December, said Keisy Bonano, an undergraduate at the University of Puerto Rico at Cayey.

“Cayey still has many areas where there’s no electricity, there’s no water,” said Bonano, who does research at the University of Puerto Rico’s medical sciences campus in San Juan. She lost lab supplies due to power outages, and her zebrafish larvae died after their incubators shut down.

Even the parts of the island that weren’t directly hit by the hurricane, such as the western municipality of Mayagüez, lost electricity and access to running water.

Andrea Rivera

Andrea Rivera

Before the hurricane hit, Andrea Rivera, an undergraduate student at the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez, split her time between a lab at the Mayaguez campus and a lab in San Juan that she became involved in through a Step-Up internship with the National Institutes of Health. In the aftermath of Maria, Rivera has continued to commute two hours to the lab in San Juan, where she works from Friday mornings through the weekend.

Many roads in Utuado were damaged or obstructed by the storm.courtesy of HECTOR JIRAU

Many roads in Utuado were damaged or obstructed by the storm.courtesy of HECTOR JIRAU

“I, fortunately, have electricity and my water running, but many of my friends don’t right now,” Rivera said. “Everyone is sharing their rooms … we’re students, we don’t have a lot of money so we’re trying to help each other out because it’s been a rough couple of months.” Because areas of Mayagüez still lacked power, Rivera said, the university picked up some of the slack by keeping libraries open until midnight.

Tents and flashlights

In late October, classes resumed at the University of Puerto Rico in San Juan. With electricity still out in many buildings, Rodríguez-Martínez said, a number of the larger lectures were given outside in tents. “It was an interesting scene, looking at the professors teaching under a tent and especially doing genetics courses and organic chemistry courses outside of the classroom.”

Classes also resumed at the campus in Cayey, Bonano said, with similar workarounds. “The science and math buildings are the only two buildings (at the Cayey campus) that have electricity, so we’re taking classes with flashlights pointing to the board so we can see,” she said.

Across the island, a sense of normalcy has started to return, even as many residents still wait for the promised recovery.

“We’re still here, we’re still striving,” Rivera said. “We want the world to know that we weren’t wiped off the map. We are here and we will succeed and we will come out of this.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Kiessling wins glycobiology award

She was honored by the Society for Glycobiology for her work on protein–glycan interactions.

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.

Simcox wins SACNAS mentorship award

She was recognized for her sustained excellence in mentorship and was honored at SACNAS’ 2025 National Conference.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.