World Food Day 2021

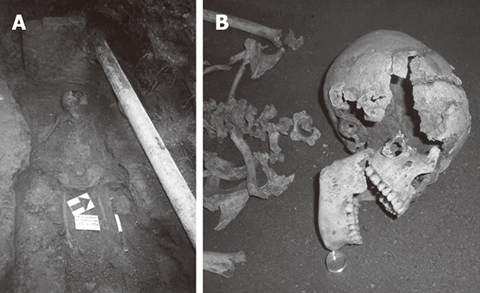

In 2008, scientists discovered a skeleton at an archaeological site in the ancient village of Cosa, in Tuscany, Italy. It was a girl from the first century, who appears to have died from malnutrition. She was short for her estimated 18 years of age, at 4 feet, 7 inches, had osteoporosis in all her bones, signs of severe anemia in her bone marrow, and tooth enamel hypoplasia, another sign of malnutrition. We don’t know her name, but I’ll call her Eleanor after my Italian grandmother.

Strangely, Eleanor was the only skeleton from that time and place with those signs of malnutrition, and there doesn’t seem to have been a food shortage. In fact, that part of Italy was a big producer of wheat at the time. While successful wheat production was probably great for the rest of her town, it may have been what killed Eleanor. She might be one of the earliest known cases of celiac disease.

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disease triggered by ingesting gluten, a protein found in wheat, rye and barley. T cells in people with celiac mistakenly recognize peptides from gluten as a pathogen and become activated. People with celiac develop antibodies against many things, including to gluten peptides, and to the enzyme that deamidates gluten in the digestive tract, transglutaminase. The disease is caused by both environmental and genetic factors; most celiac patients have the HLA haplotype DQ2 on their antigen-presenting cells. Scientists found that Eleanor had this haplotype too, when they sequenced her DNA.

The immune reaction triggered by the gluten ends up destroying the lining of the small intestine. This destruction includes flattening of the villi that line the small intestine, which drastically limits nutrient absorption and causes severe digestive problems. Chronic inflammation along with the loss of the ability to absorb food can lead to many long-term health problems: multiple nutrient deficiencies, failure to thrive in babies, dehydration, osteoporosis, anemia, increased risk of intestinal and other cancers, increased risk for other autoimmune diseases, and, if left untreated, death. The treatment, then, is avoiding gluten in your diet — entirely. If you can do that, most of the symptoms resolve, though they come back if you ingest gluten again.

While intestinal complaints are the most common path to a celiac diagnosis, in addition to these symptoms, celiac also can cause neurological and skin symptoms, including ataxia, pain, depression, brain fog, neuropathy, rashes and extreme fatigue. Some symptoms are secondary symptoms from long-term nutrient deficiencies, and some are direct results of the inflammation and improper immune response. Most of these symptoms also resolve on removing gluten from your diet. While there’s direct evidence of the nutrient deficiencies in Eleanor’s skeleton, we are left to only guess at what other symptoms she was faced with that weren’t preserved in her bones.

I was diagnosed with celiac too, a little over two years ago, but my life trajectory looks pretty different from hers. Much of this is because of the work of countless scientists over the years.

In 1887, English pediatrician Samuel Gee described the symptoms of celiac and suggested it might be treated by diet. Over the next few decades, doctors proposed various diets, getting closer and closer to the real cause, and in 1950 Willem Dicke, a Dutch scientist, proposed a diet excluding wheat and rye and showed that it worked (maybe there wasn’t much barley in the Netherlands?). In 1953, Dicke and two colleagues identified gluten as the component of the grains that was harmful. And we were off and running.

Nowadays, thanks to the work of many more researchers, you can be diagnosed relatively easily, with a blood draw to look for the hallmark antibodies and an endoscopy and biopsy to look for intestinal damage. When those both came back positive for me, my doctor said, “Well, good news and bad news. Bad news: You have celiac disease, and you can never eat gluten again. But good news: You’ll feel a lot better really soon.” That kind of straightforward answer and direction is a reason I’m incredibly thankful to be living in 2021.

I was pretty shocked though, when I learned I had celiac. I was expecting the test results to come back negative and for the doctor to have no real answer for why I felt so badly. But instead I got this gift and this curse. I could feel better! But it would be really difficult to do.

I used to love eating. I would eat anything and everything. There’s something very comforting and joyful about eating food together with friends and family. “Want to get dinner?” was probably the best thing you could say to me, aside from maybe, “Paul McCartney is downstairs, and he wants to say 'Hi.'” I baked a lot, made surprisingly good sourdough bread, and, according to my old roommate, the best banana bread.

Traveling was one of my favorite things to do too, mostly because I got to eat all kinds of stuff I’d never seen before. A good chunk of my time traveling was spent in restaurants or at stands on the street selling I-dunno-what, pointing to what I wanted to buy, and excitedly tasting whatever the heck I’d just bought.

All that freedom was suddenly gone in an instant, and I had suddenly become a very high-maintenance person. Now the thought of going to a restaurant or eating anything outside my own home is mildly terrifying. For the whole first year, I had recurring dreams where I’d forget I couldn’t eat gluten and accidentally eat something normal like a goldfish cracker and get sick.

I learned to read every ingredient on labels and scan for less obvious things, such as soy sauce (usually fermented with wheat), that’s in a lot of savory foods or malt flavoring (usually made with barley) that sneaks into foods you'd think would be gluten free like Rice Krispies and Lindt chocolate.

But I quickly realized that avoiding food made with gluten was the easy part. The real challenge — the thing that makes it so hard — is that the immune system is super sensitive. It’s designed to seek out the tiniest amount of pathogen, a few bacteria for example, and kill it before it kills us. In this situation, though, it means that avoiding gluten means really avoiding gluten — like avoiding just about every molecule of it. Some research suggests that as little as 2 miligramsof gluten is enough to trigger the reaction in a person with celiac. And those reactions can last for days with stomach pain, digestive issues, body aches, headaches and fatigue. Put another way: 2 miligrams of gluten is about one one-thousandth of a slice of bread, the equivalent of one crumb left on a stick of butter from someone reusing a knife or a dot of soy sauce marinade stuck on a shared grill. Then there’s the mystery of food processed on the same equipment in a factory. I still have no idea what that means for me. I generally stick to certified gluten-free food when I can, which means it has been tested and contains less than 20 parts per million gluten.

Avoiding gluten also means that at potlucks, cookouts, friends’ houses and most other social events, including work events, I just go to see the people. The first time I went to a social event and didn’t eat the pizza or drink the beer, I felt like a moron. I didn’t even really know where to look or where to put my hands. But I have since discovered that I do still enjoy hanging out with friends and co-workers, even if everyone else is eating and I’m not. Would I like it if there were well-labeled and clearly uncontaminated gluten-free options at social events? Of course. Giving me certified gluten-free food is a very easy way to become my friend.

It seems like that might have been true for Eleanor too. We don’t really know what people knew about celiac back in Eleanor’s time, but there is evidence from the isotopes in her bones that she may have been altering her diet, trying to alleviate her symptoms, eating a higher percentage of fish and meat than an average person in her town seems to have. Maybe she’d figured something out and was trying to help herself. I wish I could bring her some gluten-free snacks, hang out and tell her what we know now about celiac, and tell her that she could be OK.

I wonder if anyone tried to help Eleanor get well. I think about what the years leading up to my diagnosis felt like: My skin hurt, my head hurt, my muscles hurt. I was constantly sick, constantly tired, and could not figure out why. Nothing I did helped. I guess she felt like that her whole short life.

And here I have hundreds, maybe thousands, of people who've been going to work every day, pipetting, making PowerPoints, trying to keep their cells uncontaminated, and troubleshooting their assays all to find ways to help people like me get well.

This is, by far, the best time in history to be diagnosed with a chronic disease like celiac. There are celiac specialists at most major hospitals, and there are currently no fewer than 13 drugs in various stages of clinical trials. These drugs, building on decades of research, are aiming to do everything from break down gluten in the gut, to tightening up the tight junctions between endothelial cells, to blocking various points in the immune response, and to even induce immune tolerance to gluten. My doctor at my last visit said I might be able to participate in one of two clinical trials; there’s so much research, I have to choose which trial to participate in.

But there's still work to do. As of now, there are no drug treatments, and most of the drugs in the pipeline, while absolutely incredible, are to be taken along with a gluten-free diet to minimize the symptoms that still persist (unfortunately there are many) or to minimize the effects of miniscule quantities of accidental gluten exposure. These would be a huge help, and if they get approved I’d certainly take them in an instant! But celiacs will probably still be relying on a gluten-free diet for a while longer.

And even doing my best on the gluten-free diet, I'm still calling out sick from work frequently due to persistent symptoms. In fact, I wrote part of this article from my bed during a sick day. When I look on celiac message boards and Facebook groups, there always are posts seeking advice for how to deal when their boss won't allow them to take more sick days but they really can't go in because they are sick again. I'm lucky to have a kind boss and to work in a lab that lets me have flexible hours. But we definitely need a treatment besides gluten-free food to help people live their lives more freely.

And there’s societal work to be done too. Although, thanks to activists already, gluten-free food is easier to find than ever and there are some protections under the ADA, it can still be problematic in many situations. Since food pantries rely on donations, there is no guarantee that there will be gluten-free food for celiac clients. Similarly, if you are elderly and celiac, nursing homes are required to have doctor-prescribed diets, including gluten-free diets, but assisted-living and other senior communities are not. A little digging turns up stories of schools, prisons and even hospitals not being equipped to provide gluten-free food. Planes and hotels are another challenge. More relevant to the everyday life of scientists perhaps is a lack of guaranteed gluten-free food at science conferences and events. And there’s also the added expense of certified gluten-free foods.

We've come a long way, and my life is immeasurably easier than those in generations before me, thanks to countless scientists and activists. And we still have a way to go.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.