What is success for women in STEM?

Two female biochemists on opposite sides of the planet found a common interest in supporting women in STEM. Here they share their stories, experiences, how they connected and how they are combining their science experiences with the traditional methods of social scientists to enact change.

Talk about your early interests and influences.

MARILEE: Most of my science and math teachers were nuns, and I was a Girl Scout, so I always assumed that women were a big part of science and could be in charge. I loved biographies, books about clever girls and superhero comics; there was never any doubt I could choose what I wanted to do with my life — and I chose science.

Marilee Benore is a professor at the University of Michigan–Dearborn and studies vitamin transport. She was a founding regional director and former chair of American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Student Chapters, has served on the society’s Education and Professional Development Committee, and is a member of the Women in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Committee.

RANA: I spent many evenings with my father reading Scientific American and National Geographic and discussing the latest advances in science. This led me to want to be a scientist and pioneer — to explore the world around me to discover the magic and wonder of nature.

I got a thrill from understanding how molecules interact. Organic chemistry and biochemistry classes were heaven. I was enthralled and awed studying these topics. I would write poetry during the exam because of the elation I felt.

MARILEE: In high school, I coached grade school girls basketball and volleyball, and while I lacked athletic talent, I was a good coach and enjoyed supporting young women.

My college required a focused minor with a thesis, so I selected women’s studies. I did volunteer work and wrote for an underground feminist newsletter. I convinced my advisor to let me direct a community outreach project for women instead of writing a research paper.

RANA: I grew up in a family of eight girls. I was the eldest. My parents chose not to have a TV and instead focused on human interaction. We spent our time reading novels, role playing and debating. This trained me in critical thinking, how to engage and convince and how to ask questions. I grew up as a Muslim, and I learned by living Islam to be critical, to use my mind and to question. I learned that it was okay to be wrong and we can only learn from our mistakes.

How did your education and careers evolve?

MARILEE: I studied chemistry, but after a stint in the manufacturing industry exposed me to some ugly sexual harassment, I returned to grad school.

RANA: My father was a physician, and I was the eldest and smart so it was the natural thing that I would be one too, but I chose not to be a physician, because I was afraid I might harm someone by mistake. I became a scientist because scientists find out what causes disease and can help humanity.

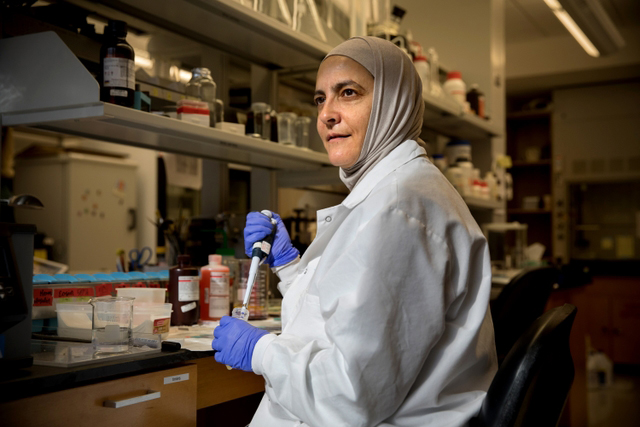

Rana Dajani is a professor at Hashemite University in Jordan and author of the book “Five scarves: Doing the impossible — if we can reverse cell fate why can’t we redefine success.” She organized the first gender summit for the Arab world in 2017.

There were no Ph.D. programs in Jordan, and although I was accepted to Cambridge University, I was unable to go for financial reasons. I became a teacher and introduced young students to the magical world of science, but in my heart, I wanted to be a scientist.

MARILEE: I took a teacher/scholar position at a primarily undergraduate college so I could combine research, teaching and mentoring. I created a Girl Scout summer day camp with other female science, technology, engineering and math faculty, but outreach was not yet valued, and my senior colleagues pressed me to prioritize research in order to be tenured.

RANA: When I got the chance to apply for a Fulbright scholarship, my husband, who was a lieutenant colonel in the Jordanian air force, resigned so we could go as a family to the U.S. I involved my children in my research and asked for their opinions about the data. They were part of my journey and success.

MARILEE: As soon as I was tenured, I expanded my teaching into interdisciplinary coursework and developed classes in diversity, inclusion and gender in science and engineering, although my teaching focus is still primarily biochemistry.

RANA: I returned to Jordan to establish my own lab, aiming to do state-of-the-art research with minimal resources. I took a long time to find the right question. My lab today is the world leader on the genetics of the Circassian and Chechan populations.

At one point, I realized that women scientists don’t have time to network after hours, so I developed a mentoring program called “Three circles of alemat” (“alemat” means “female scientist” in Arabic). The program has a holistic approach that is personal and professional and is very easy to implement.

My motto is, “A scientist sees what everybody sees but thinks what no one has thought.”

Talk about your recent work.

RANA: When I introduce myself, I like to say that I play five roles in my life or I wear five hats — but I don’t wear a hat, I wear a scarf, so I say I wear five scarves. My roles include being a mother, a teacher, a scientist and a social entrepreneur.

My fifth scarf I did not choose. A few years ago, an organization in Britain chose me as one of the 20 most influential female scientists in the Islamic world — that’s 1.6 billion people. They gave each of us 20 a title: The cardiologist, the mathematician … and I was the “Islamic feminist.”

At first, I said, “No, you can’t do that,” because when you say Islamic, the Western world looks at me skeptically, and when you say feminist, the Eastern world looks at me skeptically, and I end up with nothing. I asked them to change it, and they responded, “No, Rana, what you write about, what you reflect and what you stand for is your title.” Since then, I’ve been on a journey or pilgrimage to redefine what that means and own it rather than letting it own me.

I embarked on a journey to interview female scientists from around the world to understand better the challenges they face in their careers. I created a list of questions to unpack the root cause of having fewer women scientists. I then expanded the interviews to include women in senior career positions across disciplines, sectors, cultures and religions.

With the support of an Eisenhower fellowship, I interviewed more than 100 women in the U.S.; then I expanded my reach to interview women in Europe, India, China, South America and Africa. The answers all were the same. Women try to mold themselves to the existing white male framework rather than creating their own framework based on their priorities and needs. This applied not only to women but to all minority groups.

MARILEE: I am in what I call the third third of my life. I spent the first 30 years gaining the education and experience I needed and the next 30 happily doing research and teaching. Now I want to focus on a topic with which I can continue to give back to science, and I decided that an under-studied area was why some women persist in STEM while others leave. Much past research was identifying and changing negative behaviors that exacerbate the leaky pipeline. I thought an opportunity to hear from successful women would be heartening.

I knew that oral history research could provide insight into behavior. I began outlining and learning the psychology and anthropology I needed to conduct surveys and interviews to gather stories from successful women.

How did you hear about each other?

MARILEE: While seeking collaborators, I kept coming across the name of Rana Dajani, who had done similar video work as a Harvard Radcliffe fellow. I sent her a copy of my proposal, and she said it was like talking into a mirror. I was so excited.

RANA: When I received this email from Marilee, it was so wonderful to find someone who had the same ideas and intuition and reflections. We came from opposite parts of the world, yet we both had reached the same conclusions concerning women in science. This points to the universality of the challenges women face, how much we have in common and how we should work together to change mindsets.

MARILEE: I had been feeling a bit unsure of the value of the work, so having Rana confirm the need was precious to me. We began to communicate. Rana came to the U.S. at the same time I went to Europe to begin gathering my oral histories.

RANA: We want to use our scientific minds and skills to approach this problem just as we do with any scientific problem or challenge. We want to learn from each other and build on that learning to create a better world for future generations.

What have you learned so far?

MARILEE: In France and Romania, I met professional women and heard their stories through surveys, phone calls and videos. A few things are clear: Women stay in STEM for many distinct reasons, often personal, but many do not feel as successful as you might expect given their positions in top universities and labs.

Self-efficacy is linked to success, and role models and stories are linked to self-efficacy. My early data indicate that over 80% of the women respondents rated stories about women as significant or important to them. This agrees with Rana’s findings that women too often try to fit the wrong mold. I want to continue to conduct surveys and oral histories, find the threads of persistence, and share the stories so others can gain from the insight and experiences of successful women.

RANA: As a scientist, I approach this challenge with the scientific method. When I look around me, in Jordan and in the Arab world, I find a higher percentage of women than men in the STEM fields, at least in undergraduate and graduate education. Maybe there’s something here that the West can learn from us: How do we get more women into STEM compared to the West?

The challenges women face are similar all over the world regardless of culture, religion and background. The problem is that the workplace was designed by men for men — and when women entered the workforce, they didn’t change it. They tried to mold themselves to fit it because they assumed that was the only way of success.

I want to propose a paradigm shift, actually asking women what they really want.

MARILEE: Ensuring that all people interested in STEM have ample opportunities to have successful careers is critical for equity and the economy. Education and professional development should be supportive and inclusive; a lack of encouragement and support creates inequity.

Rana points out the number of women in STEM is 50% in some nations — nearly double the U.S. stats — suggesting we can do better.

Why is this work important to you?

MARILEE: I enjoy science so much I want everyone who loves it to have the opportunity to learn, become a scientist or engineer, or even be a citizen scientist. We can only accomplish that if we know what we are doing right, or wrong, to encourage STEM learning and appreciation.

RANA: We owe it to future generations to tell them who we are, to give them role models from us and within us.

I’m a scientist, so I get to put science into everything. This reminds me of the butterfly effect. If each one of us can do one small thing in changing ourselves, changing our family, changing our community, then we can create a change that spreads all over the world.

It starts with you, you know. You owe it to humanity, you owe it to yourself. So go out there, be the change, be the butterfly.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Kiessling wins glycobiology award

She was honored by the Society for Glycobiology for her work on protein–glycan interactions.

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.

Simcox wins SACNAS mentorship award

She was recognized for her sustained excellence in mentorship and was honored at SACNAS’ 2025 National Conference.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.