The bacteria show

Irradiating bacteria into cool shapes. Making E. coli with GFP-encoding plasmids glow under fluorescent light. These are not the late-night shenanigans of a couple of bone-weary lab mates. In the hands of popular bio artist Zachary Copfer, they are the tools of creation.

|

|

|

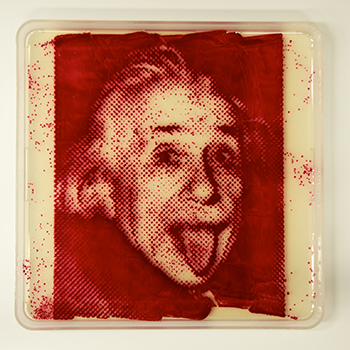

The Einstein bacteriograph.

|

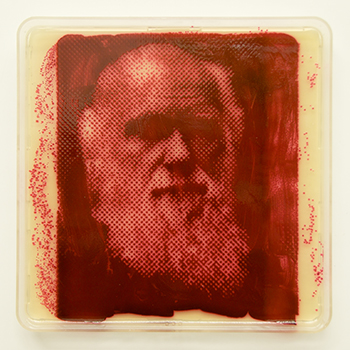

Charles Darwin emerges from Serratia marcescens.

|

A self-titled “microbiologist masquerading as an artist, or an artist masquerading as a microbiologist,” Copfer has gained popularity in the world of bio art by doing unique work with bacteria. Coper makes “bacteriographs,” images of iconic scientists and celebrities that look, on first inspection, like pop-art altered photographs or lithographs but are in fact colonies of bacteria manipulated on agar plates.

Zachary Copfer

Zachary Copfer

In his “My Favorite Scientist” collection, Albert Einstein and Charles Darwin receive the bacteriographic treatment, their faces appearing in tan agar against a background of maroon Serratia marcescens. Individual colonies of the bacteria dot the periphery of the plates as if ready to be plucked up by an inoculating loop. S. marcescens produces the tripyrrole pigment prodigiosin and gives the images their deep red color.

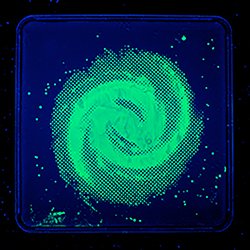

Another of his collections, entitled “Star Stuff” as a nod to Carl Sagan, features images taken from the Hubble telescope that are grown in E. coli containing GFP-encoding plasmids. When visualized under ultraviolet light, the Milky Way comes to life in fluorescent spirals of E. coli. The single colonies appear as neighboring stars against the night sky.

“People can be passionate about art and science and be interested in both,” says 33-year-old Copfer, who has degrees in biology and fine arts and worked as a pharmaceutical researcher until his passion for art, theater and photography won out.

“When I first went to (fine arts) grad school I put science on the shelf for a while,” he says. But while brainstorming ideas for a project, Copfer came across Carl Sagan’s television series “Cosmos” on Netflix.

“The introduction to the first episode is beautiful and amazing,” he says. “(It shows that) science can be poetry. I’ve always been amazed by that and tried to figure how to get that into my art.”

Bio artists like Copfer are often champions of scientists and of communicating science to the general public. “Science is very creative and that is something that people who aren’t in science wouldn’t expect,” he says. “They think of it as dry, people in lab coats crunching numbers, very removed and sterile, when it couldn’t be more of the opposite! People are excited and emotional about their research.”

Copfer says when he first started making bio art he was most interested in sharing the beauty in science. That intention is still there, but it’s shifted a bit over time. Now he’s also trying to have fun with science.

Choosing bacteria as a medium has kept things fun. “(Bacteriography) is so much more rewarding than regular photography; by looking at it, you realize that this image is living,” he says.

A Milky Way of E. coli.IMAGES COURTESY OF ZACHARY COPFER

A Milky Way of E. coli.IMAGES COURTESY OF ZACHARY COPFER

But inventing a means of growing a live photograph wasn’t easy. There was a significant period of trial and error before the bacteriographic process really gelled. “The only thing I had to go from was dark room photography. No one had ever done this,” he says.

Copfer uses halftone images of his subjects as a type of negative that he places above a full plate of bacteria. He then irradiates the negative and plate with short-wavelength ultraviolet light that kills any bacteria left exposed by the halftone image and leaves the bacteria in shadow to grow. This results in bacteriographs that look like pixelated photographs of his subjects. Copfer has made bacteriographs of Pablo Picasso, Leonardo da Vinci, the British actor Stephen Fry, celebrity mathematician Carol Vorderman and the queen of England.

Challenges are similar to those found in a lab: determining optimal growth temperature, time and concentrations of growth media ingredients. In stark contrast with regular photographs, Copfer’s bacteriographs require extensive preservation methods, which he says was one of the biggest technical blocks to creating this kind of art. It was tricky finding an appropriate resin to preserve but not dehydrate the bacteria and agar so that the plates could be safe to handle and display. After significant experimentation, Copfer found ideal sealants that he applies after he’s irradiated a piece’s remaining bacteria. This allows his art to travel nationally and internationally to science expos and galleries.

Copfer doesn’t see himself as an art-world anomaly. He believes that scientists are intrinsically artistic in nature and can find the creative process therapeutic. “Most good research isn’t cut and dry. It requires creativity,” he says. While art “allows people who are struggling or stuck in a routine a great outlet … (and a chance) to look at things differently and to put things in a different context.”

His advice for anyone with a background like his who is interested in pursuing the arts? “You can’t be afraid to screw up or pursue every dumb idea. It is about having fun, letting go and being absorbed by the things that make you excited … Don’t see it as a waste of time. Give it the same time and energy that you would give your research because it is just as valid and just as important.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Kiessling wins glycobiology award

She was honored by the Society for Glycobiology for her work on protein–glycan interactions.

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.

Simcox wins SACNAS mentorship award

She was recognized for her sustained excellence in mentorship and was honored at SACNAS’ 2025 National Conference.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.