Nights and days in the lab

The first family death I witnessed was one of my younger cousins who had sickle cell anemia. It was devastating. A close family friend also suffered from sickle cell, and her crisis episodes were painful for many in our community. As I neared the end of high school, a cousin who was my contemporary was diagnosed with leukemia. He went through a series of treatments and a bone marrow transplant and was in remission for a couple of years before he died. These experiences fuelled my desire to become a scientist researching cures for diseases.

to study the composition of medicinal plants.

When I first embarked on my Ph.D. in biochemistry, I experienced some financial hardship and was tempted to give up, but with help from the university’s postgraduate funds administrator, Jadah Matentji-Masuku, I received a bursary (scholarship) from the National Research Foundation South Africa for one year. I had to pay most of my expenses out of pocket, and I survived on the generosity of some good souls as well as the proceeds from selling African print fabrics, hair extensions, jewellery, snacks and moringa products — a side business.

My first scientific research was in the biochemistry department of the University of Ilorin, Nigeria. For my honors degree project, I prepared a feed formulation, which I fed to lab rats. Then my colleagues and I euthanized the rats, removed various organs and measured specific enzymes in the organs. The preparation of the feed went well, but some of us found the euthanizing of the animals unnerving. Properly euthanizing and dissecting the animals was essential for our investigations.

For my master’s research at the same university, I had to learn how to breed albino lab rats because the supply was not enough to meet our research needs on campus. I used some of the rats for my own work; others I sold to colleagues.

I was investigating the effect of a generic drug on African sleeping sickness, and sometimes I slept in the lab, on the cold floor in the academic space or on a hard table with books as pillow, because my experiments were either on a 12-hour clock rotation or had to be monitored closely.

I completed my research work ahead of most of my colleagues and before my course work was over. I don’t know if other students had to work through the night — I was mostly alone in the lab monitoring my lab rats and collecting their blood samples.

I moved to South Africa and began to study advanced glycation end-products and medicinal plants. My department laboratory did not have certain resources I needed for my study, and our molecular biology laboratory was still under construction, so I frequently visited the laboratory at the Tshwane University of Technology, Arcadia–Pretoria, where one of my supervisors was employed.

Sometimes I stayed overnight in my home lab to prepare for an experiment, then took a bus at daybreak to the other lab in the next town so I could complete the next step of my experiment. A spectrophotometer that was key for my research was available on my campus, but the operator’s daily shift ended at 4 p.m. Because some of the protocol for my experiment was time-bound, I had to start my preparation at dawn to finish the cycle before 4 p.m.

Isolation of bioactive compounds was not part of my original objective for my Ph.D. program, but I shared lab space with researchers from the chemistry department of my institution, the Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University. I watched them perform their experiments and sometimes assisted them with their investigation. Olivier Mutendela gave me my first insight into chromatography and isolation, and Isaac Masilela loaned me my first isolation column. Finding relevance to my study, I decided to incorporate it into my protocol.

My research crossed over into phytochemistry, and I found that my niche was studying the chemical composition of medicinal plants to identify and isolate unique phytochemicals for drug discovery.

My first isolation procedure took me on a six-night no-sleep journey. I manually collected the elutes from the column chromatography set-up, taking about 45 minutes to fill each test tube. I had to stay awake to change test tubes for each collection. Automated prep high-performance liquid chromatography equipment would have done this faster, but that equipment was not available. I manually collected each of the compounds, which were mostly separated by color. Then, with further testing using thin-layer chromatography plates, I isolated some unique compounds and made discoveries that validated my findings. I linked the presence of a compound, a precursor for synthesis of others, to the unique character displayed by one of the plants of interest. Despite the rigor, I fell in love with this aspect of research.

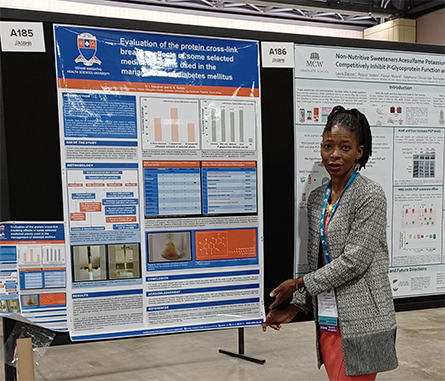

ASBMB annual meeting in Philadelphia.

My doctoral journey taught me the importance of collaboration and asking for help. I received that help from multiple departments at my institution and my co-supervisor’s institution — specifically, the departments of chemistry, biology, pharmaceutical chemistry and chemical pathology let me use their infrastructure and sometimes provided chemicals I needed for my work. My work also crossed into my institution’s virology, microbiological pathology, physiology and pharmacology departments.

I learned to stand on the shoulders of giants, people with years of experience who were willing to help me. I once walked into the office of a school head, the late Gboyega Adebola Ogunbanjo. He invited me in, we drank tea as I discussed my research with him, and he took time to read the first draft of my thesis literature review and meticulously edit it. That was a huge gift.

At the tail end of my study, my office was allocated to a new staffer and I had no work space. The head of the biology department, P.H. King, offered me the use of the honors students’ lecture room. There, I set up a makeshift food bar with tea, coffee and microwavable snacks. I also had a change of clothes and a blanket. I camped overnight when my investigation ran late. In the morning, I’d wash in the ladies’ room and finish my day’s work before returning home to take my bath and have a proper sleep. I was able to complete the writing of my thesis with the use of this space.

Other, smaller gifts have been no less precious: Friends, family members and acquaintances gave me both financial and material support. I also treasure the times that friends such as my former office neighbour, Chepape Semenya, brought me food and refreshment, just to say “Hang in there.”

I recently submitted my Ph.D thesis for final evaluation. After completion of my doctoral degree, I hope to answer some of the questions that my investigation brought up, as a researcher in academia. I’d like to teach and lecture at a research institution where I can instruct both undergraduate and postgraduate students in the sciences, especially biochemistry.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.