Winners of the ‘aha moments’ essay contest

To celebrate our three journals going open access, we invited readers to share their moments of discovery in science. Here are the first, second and third place winners.

FIRST PLACE

Finding a common ancestor

By Richard Ludueña

As a child, I loved science fiction. I always have liked history, and I especially was drawn to stories about time travel, because I loved to imagine looking far back into the past.

My aha moment came in 1972 when I was a graduate student in Dow Woodward's laboratory at Stanford determining the first 25 amino acids in the sequences of alpha- and beta-tubulin from chickens and sea urchins. At that time, very little was known about tubulin sequences.

The results came off the sequencer around Christmas Day. I realized that chicken and sea urchin α-tubulin were about 95% identical and that the same was true of the β-tubulins.

This meant that I had just learned something very intimate about the common ancestor of vertebrates and echinoderms, an organism whose appearance and morphology were unknown and only could be guessed at. I felt like I was looking perhaps 700 million years into the past. I had no idea what that animal looked like, but I knew something about its tubulin.

I also observed that α- and β-tubulin were themselves about 40% to 45% identical, so I now perhaps was seeing more than 2 billion years into the past to the time of the first eukaryotes, one-celled organisms that lived on a planet that would be unrecognizable to us.

This was one of the most exciting moments of my career as a biochemist and the closest I ever came to realizing my childish fantasy of time travel. I think a child lives inside every scientist, a child whose curiosity is challenged by mysteries, who wants to make visible the invisible and to magnify the microscopic and who wants to look back into time as far as the origins of everything — of cells, life, the earth and the universe.

SECOND PLACE

Dreaming of Western blots

By Mindy Engevik

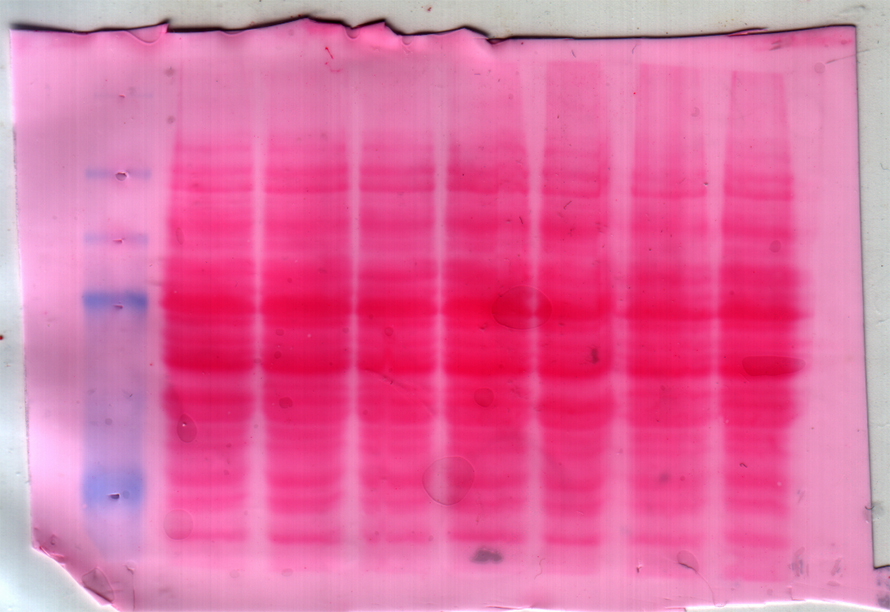

It was a cold night; the wind was blowing, and the branches of a nearby tree were scratching against the roof of my apartment. I was in bed huddled under a big down comforter, which enveloped my whole body like an amoeba. I was deep in REM sleep, dreaming of Western blots. Horrible Western blots … the bane of my existence.

As a graduate student, I was fascinated by the beautifully orchestrated events of ion transport of the intestine. I gloried over ion transporter mRNA, enjoyed functional assays in tissue cultures, reveled in measuring fecal ion concentrations by flame photometry — but then I encountered the dreaded Western blot.

I needed to measure the protein levels of the sodium–hydrogen exchanger isoform 3 and the colonic HK-ATPase in mouse colon by Western blot. Day after day, I had been troubleshooting these Western blots. I had tried optimizing the denaturing steps, removed the denaturing step, changed the blocking buffer, modified the run times … I had tried everything I could think of and everything my helpful colleagues had recommended. But to no avail — the Western blot had won.

But that night, in my dreams, I went over the Excel sheet provided by my PI that provided a handy plug-in for calculating the amount of protein to add to the Western blots. I dutifully added my dream concentrations and realized … the math was wrong.

I bolted awake, ran to my laptop, checked the Excel sheet and voila — the Excel sheet math equation was incorrect!

That morning, I went to lab, added the correct amount of protein, and this time, the Western blot worked. I felt like a conquering hero. I guess dreams really do come true.

THIRD PLACE

Beauty in brown

By Kazuhiko Igarashi

The laboratory where I started as a new faculty member, led by Norio Hayashi and Masayuki Yamamoto, focused on erythroid cells: Colleagues were working on the regulation of heme synthesis during erythropoiesis, and I was trying to identify transcription factors that would regulate globin genes by binding to their superenhancers, the locus control region, together with two graduate students.

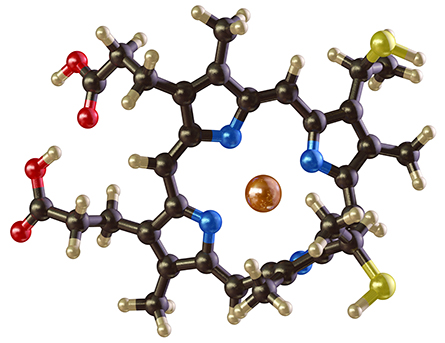

One student, Ken Itoh, got two promising candidate cDNA clones in two hybrid screenings using MafK, one of the subunits of nuclear factor erythroid 2, as a bait. The other student, Tatsuya Oyake, expressed one clone in E. coli for purification. When he came out of the cold room, he was disappointed, thinking that his purification was a total failure. The protein solutions looked brown.

We were troubleshooting in front of the cold room, with the tubes in his ice box. Then our lab head, Norio Hayashi, who has a long track record in enzymes of heme synthesis, happened to walk by. It did not take a second before he saw the tubes and suggested carefully, "This may be a heme protein."

A beauty emerged: Heme, which is massively synthesized during erythropoiesis, would regulate the activity of this transcription factor, BACH1, coordinating heme synthesis and globin gene expression.

As so many scientists know, the simplicity of a model does not guarantee a simple way forward. For us, it took another two decades to come to a reasonably correct answer on the function of the heme–BACH1 axis in erythropoiesis. Various functions of BACH1 and the other clone, BACH2, which also is regulated by heme, have emerged in not only erythropoiesis but also iron and heme metabolism, immune response and cancer progression.

If Tatsuya had discarded the tubes out of disappointment or Professor Hayashi had not seen those tubes, what would we be doing today?

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.