A tale of two ZIP codes

Memphis is a renowned, multifaceted gem of the Midsouth that tells its story through the cultural outpouring of diverse attractions like the National Civil Rights Museum, Sun Studio (the birthplace of rock ’n’ roll, where musical legend B.B. King was discovered) and world-class barbecue. Memphis is also home to some of the worst inequity in the U.S.

April is National Minority Health Month, a time to reflect on the importance of closing racial and ethnic gaps in health disparities and consider actionable goals that can improve the quality of life across our communities.

Disparities in access to healthcare or in outcomes for different health conditions are important topics that receive substantial attention. But what comes before healthcare? Basic needs that are the right of all humans: food and air.

Disparities in access to clean air and fresh food are major predictors of the prevalence of so-called diseases of poverty (i.e., obesity, diabetes and hypertension). The lack of access to fresh food and clear air precipitates a domino effect in the predisposition to more fatal illnesses, such as cancer, stroke or compromised ability to fight infection. Although there are genetic causes to these illnesses, much of the pathology is triggered by behavior and poverty.

My origin motivates me to understand better the variances in lived experience between the privileged and the needy.

I think of my mom — a Honduran immigrant who came to this country for opportunity, struggled as a young mother, and is now an executive who teams with my dad to put on the largest back-to-school event in the state of Florida, which provides medical screening, school supplies, backpacks and other essentials at no cost to those in need.

Lessons from my mother have inspired my own community involvement in every place I’ve lived, most recently as a founding member of the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Black Employees and Allies Resource Group. My mom taught me you don’t have to belong to a particular group to recognize or act on a need.

I came to Memphis to advance my scientific training at a premier research institution, and now, as a father of two, my motivation has intensified to improve our society for the next generation.

I reflect on the poor air quality and unhealthy food many children consume at school, and improving these aspects of daily life would be an important step toward improving our society. My hope is that shedding light on the situation can stimulate action here and beyond.

As a contributor to ASBMB Today and writing for such an important purpose, I found someone to engage in conversation about Memphis, and the conversation went from local to global.

Local experiences, global application

Miguela Caniza is an infectious diseases expert and the director of the Infectious Diseases Program of St. Jude Global, an ambitious initiative to enhance the global quality of pediatric care by providing access to better therapies and improving the standard of care.

During her master’s of public health training at the University of Memphis, Caniza studied health and environmental contamination across Memphis ZIP codes and now travels all over the world to train and equip healthcare providers in mostly developing nations.

“Memphis is an incubator, a lab for the world, because there is so much disparity in Memphis,” Caniza told me. “Although markers of environmental contamination can be correlated with diseases of poverty, access to fresh water, fresh food and clean air have profound impacts on health. Thinking about Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil, they are such beautiful countries with so many resources, but big companies have come in, misused the land, killed the biodiversity, and the overall health of the people has suffered.”

Speaking with Caniza inspired me to investigate further what is going on in my community as it relates to differences in health outcomes, disparities in access to healthy food, and disparities in air quality across ZIP codes.

Proximity in location, distance in air quality

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency performs a triennial review called the National Air Toxics Assessment that provides ambient measurements of 180-plus air toxics, identifies emission sources and correlates this data with health risks such as respiratory illness.

Sperling’s Best Places is a market data analysis firm that analyzes NATA and other data to provide interpretable and reliable analysis down to the ZIP code level.

Using the NATA data, SBP created an air-quality index where 100 is the best air quality in the U.S., and the average ZIP code scores a 58.

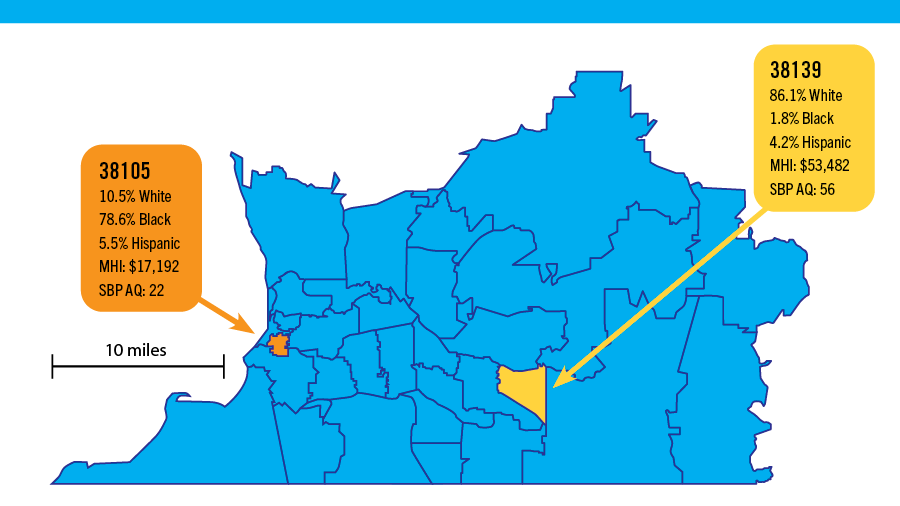

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital is the premiere pediatric treatment and research facility in the United States, employs some of the world’s top minds and is intrinsic to Memphis’ identity. St. Jude also is located in one of Tennessee’s most impoverished ZIP codes: 38105.

38105 scores a 22 on the air-quality index and has more than double the risk for respiratory illness of the state of Tennessee or the U.S. overall.

According to SBP, the 38105 population of 6,449 residents is 10.5% white, 78.6% Black and 5.5% Hispanic. It has a median household income of $17,192.

A 30-minute drive east takes you to ZIP code 38139, where SBP reports an air quality index of 56, half the risk for respiratory illness of 38105. 38139 has a median household income of $53,482 and a population that is 86.1% white, 1.8% Black and 4.2% Hispanic.

These data show the demographic of people exposed to the highest levels of environmental contamination in Memphis.

ZIP code effect on survival

ZIP codes 38105 and 38139 are in Shelby County, and according to Shelby County Health Department statistics, the annual age-adjusted mortality rate in the county from chronic lower respiratory disease is 39.6. This rate rises to 54.2 for the downtown Memphis area and falls to 27.2 in a more affluent area.

The annual age-adjusted mortality rate in Shelby County from diabetes is 26.9. This rate rises to 32.1 in the downtown Memphis area and falls to 7.4 in the same affluent area.

These statistics seem to paint a picture that health needs wealth, and in Memphis, wealth is often white.

Another difference is access to fresh food and groceries. There are seven locations of the main grocery store chain in the region within five miles of 38139 but only two locations within five miles of 38105.

Having to travel at least five miles, depending on where in the ZIP code one may live, might not seem like a long distance, but for individuals without reliable transportation or access to public transportation, it is an exceedingly difficult task to travel just to have access to groceries.

On the other hand, fast food is readily available. There are eight locations of a major global fast-food chain within five miles of 38105 but only five locations within the same distance of 38139.

Call to action

If Memphis is a laboratory, then why not do an experiment?

Since access to fresh food is limited, what if local masters of cuisine used their skills in the culinary arts and resources from their businesses occasionally to sponsor a school in 38105 and the downtown Memphis area to provide better food options and maybe even teach the children and their families how to cook? Schools can be great hubs to create initiatives in the community, and their partnership could help provide schools with good food and pass on employable skills.

This also could be an opportunity for schools to teach the taste buds of children who are not regularly exposed to fresh produce at home. Children who grow up learning about this might adopt better eating habits as adults.

On the other hand, local government could incentivize food companies, such as major grocery store or supermarket chains, to open more locations in low- to middle-income areas or even open miniaturized versions of the stores just to have a presence and serve these underserved communities.

Another aggressive idea might be for local government to stop enabling the opening of the same fast-food chains and lure more alternative food options so residents conveniently can access a broader menu of hopefully healthier options.

A radical idea would be to use existing resources, such as gas stations, that are readily abundant and demand they sell groceries, since gas stations are easy to get to without public transportation, especially in food desert areas.

As for the environmental contamination, a practical solution is the purposeful and intentional identification of environmental aspects that can be fixed.

Abroad, that could mean reducing the use of and reliance on plastics or not selling land to foreign investors to plant soybeans or cut trees. These changes would stimulate biodiversity and dramatically change the air quality and access to the land that is a source of living.

In Memphis, and more specifically in ZIP code 38105, that could mean creating community gardens and community-supported agriculture, educating the residents about recycling, deploying mobile units to go into underserved communities and distribute fresh food, and holding businesses accountable for their production of air pollutants.

A Memphian experiment to start to affect health outcomes by changing access to clean air and fresh food could become a template for other places across the U.S. or the world to do the same.

These ideas and data are intended to serve as a primer for conversation and action this National Minority Health Month as we consider the differences in parallel lives separated by a 30-minute drive.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.