Research on a budget

One benefit of teaching at a liberal arts institution is being in an environment that doesn’t live and die on research productivity. While faculty typically are expected to do research, this may be secondary to the teaching mission of the institution and is often for the benefit of student researchers. In other words, the goal of research is to teach and inspire rather than to produce. Produce we do, but on a slower schedule and with undergrads as coauthors.

The disadvantage of this scenario is that funds and facilities for research are typically less than at research-intensive institutions. We may not have the time or resources to bring in the big bucks to pay for cutting-edge research. Often, our funds are limited to a few thousand dollars a year provided by our college’s research office or from our own department’s budget. What can a biochemist or molecular biologist do with this level of funds for research? We all know that molecular supplies are ridiculously expensive. Take the cost of a single antibody at $300 to $500 — there goes 10% to 20% of the yearly budget.

I started seven years ago on the faculty of Andrews University, a Michigan school with fewer than 5,000 students. We have reasonable financial resources, most equipment and facilities needed for basic molecular research, and support for writing grant applications. However, this position did not come with specific startup funds (the department was generous to get me what I needed), and I have not yet had success in winning an external research grant, even those targeted at undergraduate institutions (the competition remains tough). During this time, I have developed ways of reaching my research goals on a tight budget, and I share some of them here.

Cell culture

Cell culture media can be purchased inexpensively in powdered form. Depending on volumes needed, this can be a large savings. Unfortunately, the major cost of cell culture is in fetal bovine serum, and I have not yet found a cost-effective substitute. I once tried a product marketed as an FBS substitute. It failed to support the growth of my basic and not-very-fussy cell lines. In addition to FBS, reagents for transfection of mammalian cells are often costly; an alternative to these costly reagents is polyethylenimine, very effective for transfecting HEK293T cells as well as some other cell lines.

Western blotting and immunocytochemistry

We make our own gels. This takes just over an hour; apparently, we have more time than money. Antibodies are expensive, but good antibodies can be reused multiple times with a little sodium azide as a preservative. In years past, it typically was expected that one would control for protein loading by blotting with an antibody for a housekeeping protein, such as beta-actin or alpha-tubulin. Recently, journals such as the Journal of Biological Chemistry have recommended staining membranes with Ponceau S so as to see all proteins rather than just one major protein that could be affected by experimental treatments. This has the secondary benefit that Ponceau S is cheap, much cheaper than an antibody. While I have not found a cheap source for all antibodies, the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa is a source of many antibodies for minimal cost. When it comes to performing immunocytochemistry, coverslips easily can be treated with polylysine and antibody volumes kept at a minimum — just 100 microliters will cover a coverslip. Mounting media can be made with simple components: buffered glycerol with an anti-fade such as p-phenylenediamine. Many recipes can be found online.

Transformation

If you only infrequently need basic subcloning efficiency competent cells, the cost of a commercially available preparation might not be too steep. However, for greater volumes, you can try making them yourself. Many protocols are available online, even one, the Inoue method, for making what the authors call “ultra-competent” cells.

Plasmid preparation and DNA markers

The cost of plasmid prep kits can add up if you do a lot of this work. However, they are unnecessary. I have prepared plasmids using the nonionic detergent method for many years now, paying pennies per prep, with results suitable for mammalian cell transfection and Sanger sequencing. The published method works well and can be scaled up for larger quantities of plasmid. I learned recently that make-it-yourself DNA molecular weight markers, the Penn markers, are available. These consist of two plasmids that can be purified (maybe with the nonionic detergent method) and digested with the PstI and EcoRV restriction enzymes to produce 100 base pair and 1 kilobase ladders. An endless supply for just the cost of the plasmids and a couple commonly available enzymes.

RNA purification and analysis

The best method to purify RNA is one of the many commercially available column kits. However, these come at a cost. Others are cheaper but involve the use of toxic solvents, which are best avoided, especially with novice undergraduate researchers. So there is a tradeoff in these approaches. In terms of analyzing the purified RNA, a bleach gel seems a very simple and effective approach.

Challenges to working on a budget

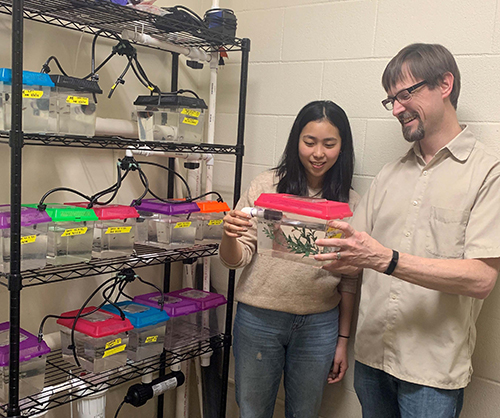

Not everything can be done both well and cheaply. As mentioned above, sera for cell culture are just plain expensive. Protein purification can be done reasonably well with simple gravity-flow columns; however, the use of an (often pricey) chromatography system would greatly facilitate the process. I have recently constructed an 18-tank flow-through zebrafish system from hardware store supplies for about $500, significantly cheaper than the $15,000 it might cost from professionals. There have been some challenges with this system, however, that have not expedited my research, one example being when filters and pumps didn’t work together as planned. Many headaches later, but with the satisfaction of having built it myself, I have it figured out.

Back when I was in graduate school, there was a technician down the hall who enjoyed tinkering in his garage in the evenings. He would construct tube rockers and similar devices for a few dollars out of basic motors and electrical clips from the hardware store. They would have cost hundreds of dollars from a scientific supply company. I think a person like this should set up shop near every major research institution.

Do you know people who are effective at making the research dollar stretch through do-it-yourself approaches? Do you have methods that work well and allow you to avoid costly purchases of kits or other supplies? Let’s continue to share ideas. I wish you all the best as you do more for less.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.