Three lessons I learned from getting kicked out of a lab

I set foot on Georgia Tech’s campus in the fall of 2014 with two letters in hand.

One was an acceptance letter from Tech, and the other was a letter from my Mieng (Khmer for aunt). I applied to six graduate programs and was rejected by all but one, so I was very grateful for Tech’s acceptance letter. The second letter was not so pleasant.

In it, Mieng wrote, “Dear Linda, GT was reluctant to accept you because of your low GRE (graduate school entry exam) results and GPA, but because Phou (Khmer for uncle) was an alumnus at the school, they extended a courtesy to him and asked him for further assessment of you. I am bringing this to your attention because I am not sure if you understand what your uncle has done for you.”

So here I was on Tech’s campus, with these two letters setting the stage for my upcoming Ph.D. adventure. Feelings of not belonging were unlocked. I rationalized that an opportunity was still an opportunity, regardless of who helped me obtain it, and that I should still take it.

As any graduate student understands, the first year is an exploratory year — we multitask with teaching classes, taking courses and, most importantly, adjusting to a research group. In the GT chemistry department, grad students participate in a rotation program to get to know the research groups and advisors before we commit to staying on board for the next half-decade. At the same time, we are competing with our peers for slots in the groups.

After going through the rotation program, I decided I wanted to work in a biochemistry group. I thought the topic was super cool and that there were a lot of research opportunities in that field. I was not the only student in my class who thought so; in fact, I had to compete with two other students from my year to earn a spot.

The biochemistry advisor decided to accept me, but he said it was on one condition: I would start working in his group in the spring, and at the end of the summer he would evaluate me and decide whether to keep me. I didn’t think twice about the risk of being rejected; I believed that if I worked hard enough I would be able to stay.

What happened that summer

Even though I worked long hours, studied additional physical chemistry, and was so anxious I was afraid to ask for time off, at the end of the summer the advisor sat me down in his office one evening and broke the news. He said he recognized my hard work but did not think I would thrive in his group. He said that because I came in with an undergraduate degree in microbiology, I should look at the biology department rather than chemistry. He could not see me doing organic chemistry, he said, and he did not have a project available that was suited to my abilities.

There I was in August 2015, one year after arriving at Tech, being rejected. I was shattered. I truly thought hard work paid off. If that’s the case, why did I fail? Why was it his words against mine? Do students not have a say on whether they belong? These questions rushed through my mind as I argued with him for two hours, trying to secure my spot. I walked out of his office defeated, my face wet with tears and snot, and my stomach in tight knots.

For the first time, I truly felt like a failure. My aunt was right, I thought; I did not belong at Tech. Feelings of failure are physical. I threw up my dinner that night, I could not stop crying, and my body would not stop trembling.

Why did that moment hurt so badly? For me, it was because I felt I had failed my family.

My mom and dad came to the U.S. as refugees in 1990, and a little less than 10 months later I was born. I grew up in a close-knit Cambodian and Vietnamese community. Daycare for me meant playing with rice dough and mung bean balls with my nhe (Khmer for an elderly aunt or grandma) as she made Khmer desserts to be sold at the local Asian markets and simultaneously kept an eye on me. We slowly moved out of poverty as my parents worked; they started by busing tables at restaurants and their careers peaked as machine operators earning $11 an hour.

My parents, like many refugee families, saw education as the key to success in the U.S., but they did lacked the English speaking skills needed to guide me through the system. As a first-generation student, I saw it as my duty to navigate the education space and relay the message to those following that path. I completed programs for gifted students in elementary and middle school, did the International Baccalaureate program in high school and earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Florida.

Then 2015 hit.

I was at a crossroads: Should I stay in the program or leave? Did I have enough mental strength to start over? Why would I want to risk failing again? To find the answers I had to look inward.

Lesson 1: The comfort zone

In the Ph.D. program at Tech, the classes are often small and the gossip is often loud. The chatter in chemistry meetings and teaching assistant labs included rumors about why I was kicked out of the group. There were snickers of “I told you so” and “she’s not going to make it past her second year.” While the noise circulated around the department and my confidence sank to rock bottom, I had to find a way to keep myself afloat. I turned to my comfort zone, the people who made me feel whole: close friends and family.

I looked to them for inspiration. Being true to myself meant recognizing the things that I identify strongly with; for me, my unique cultural background gave me a sense of warmth and pride. I come from an American subculture that is filled with delicious food, amazing people, and beautiful stories of suffering and triumph. Growing up, while eating banh xeo (Vietnamese yellow crepes) or slurping nuom choc (Khmer for noodles), my nhe and ta (Khmer for grandma and grandpa) or ba va me (Vietnamese for mom and dad) would tell stories of their times in Cambodia and Vietnam during the 1970s and ’80s. My family survived war, genocide and, in the U.S., poverty. They are my heroes. I told myself that if my family had the mental strength to overcome these life-threatening hurdles, then surely I will find the strength to overcome this academic obstacle.

a traditional Khmer dress). In the family’s culture, it is common to have roasted pig for large celebratory events such as weddings and birthdays.

What does that strength look like? It meant getting out of bed every morning (even if I had to tell Google to blast Alicia Keys’ “Superwoman”), showing up to class, sending out emails to potential new advisors and seeking advice from my allies — trusted friends, professors and graduate coordinators. As a first-generation student, I had learned from my parents’ example of hard work which helped me succeed in the classroom, but their knowledge of navigating the professional social terrain was negligible; they could not give me advice on how to negotiate with professors, to say the things that needed to be heard to get the things I wanted. I was taught to work hard. Now I needed to learn how to play smart.

Lesson 2: Broader horizons

During my first and second years of graduate school, my everyday environment consisted of my apartment and the chemistry department. In this very narrow ecosystem, I felt isolated. I could not find anyone in the department that shared my background.

At the time, the graduate program was not designed to help marginalized students; it only provided additional assistance to specific people of color. I learned this during my first year. One day, I ran into the Director of Diversity of Affairs for my department.

“My classmate told me that there was a minority student lunch today just for the first years,” I said. “I was wondering if I could join the discussion.”

He told me that I was not a minority.

“But I’m one out of only two Asian-American students in my year!”

He told me that based on the National Science Foundation definition of minority, I did not qualify, and unless that definition changed, I would not be allowed to participate in that lunch.

I could not fault him for upholding policy; however, to be true to myself and feel grounded in Atlanta, I knew I needed to be a part of a community. Undeterred, I decided to be creative. I combined my desire for belonging and my love for kickboxing by joining a Muay Thai gym where I found a group of athletes who support each other regardless of their background.

This gym allowed me to make friends outside of school. These friends were the best kind because they were not in scholarly competition with me and accepted me for my personality and not my academic caliber. By stepping out of my ecosystem, I found an environment that built up my confidence, which needed major repairs, in a place where people genuinely welcomed me. Over time, as I regained a sense of belonging, I was finally ready to broaden my horizons on Tech’s campus.

when she joined a kickboxing club.

I eventually joined a new research group, and as I progressed through my project in this group, I wanted to see what Tech had to offer beyond the chemistry department. I decided to take a course called “Social Justice and Design” at the School of Public Policy. This was my first exposure to philosophical and social concepts surrounding technology, and I was hooked.

From there it was a snowball effect. I was super excited to learn more about the thought process behind policy development and was motivated to apply for the Sam Nunn National Security Program, a special cohort of 10 graduate students from various departments within Tech coming together to tackle national security issues.

I am grateful to this program. After four years at Tech, I finally found a niche where I felt respected for my academic standing and a safe, welcoming place to engage intellectually with my peers. Broadening my horizon allowed me to rebuild my confidence and secure my sense of belonging.

Lesson 3: People are dynamic

Although my critics brought me down, they also have the potential to bring me up.

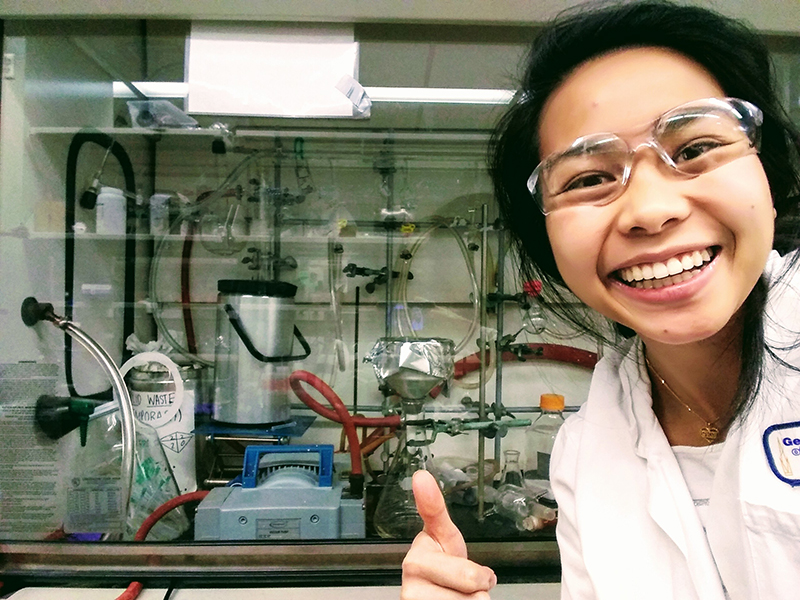

Four years after being kicked out of the lab, I am grateful to my former adviser. If I was not forced to leave, I might have stayed in an environment that didn’t suit me. I am now a proud student; I work on designing and synthesizing new materials for solar fuel cell applications. I am surrounded by supportive mentors and a patient advisor. Instead of looking at my past work, my PI looked at my potential. I didn’t have the credentials of a synthetic chemist, but he took me in because he believed in my ability to learn and grow. He often tells his students, to “trust, but verify,” and this situation was no exception.

Prior to our third interview, this PI asked my former advisor for his opinion of me and wrote it down on a purple post-it note. At our final meeting, before the official handshake to join his group, my future PI read to me what was on that post-it: “Linda is ambitious, hardworking, and likable.”

At the time, the words did not resonate with me, but today, as I prepare for the last stretch of my Ph.D., I realize my former advisor was right all along, I didn’t belong in his group; rather, I belonged in a place better suited for me. And most importantly, his observations of me were accurate, and I am thankful for his last act of advocacy on my behalf.

I leave you with this story in hopes that you too will find a sense of confidence and belonging, remember to be true to yourself, broaden your horizons and, most importantly, be supportive of others. We are all dynamic and capable of immense growth.

the material. At this point, she was filtering it.

This article is adapted from a speech Linda Nhon made at Illuminate Tech on Nov. 13. Maureen Rouhi, communications director of the Georgia Tech College of Sciences, and Benjamin Ahn of the Georgia Tech Student Government Association helped make this story a reality.

This story was first published on The Xylom, a Millennium Fellowship Project where scientists share personal, authentic stories outside of their research. It has been edited for ASBMB Today. Read the original version here.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.