Thriving as a messy Other in academia

The road to becoming a professor, particularly for people of color and those considered “Other” (LGBTQIA+, low socioeconomic status, first-generation immigrant), is rarely smooth. A quick skim of my Twitter feed shows me that the experience of being an aspiring academic while Other is alive with tears, laughter and outrage — and yet we persevere because we hope to arrive, at some point, at the dream job at a university or college we love, carrying out the research and teaching that fulfills us.

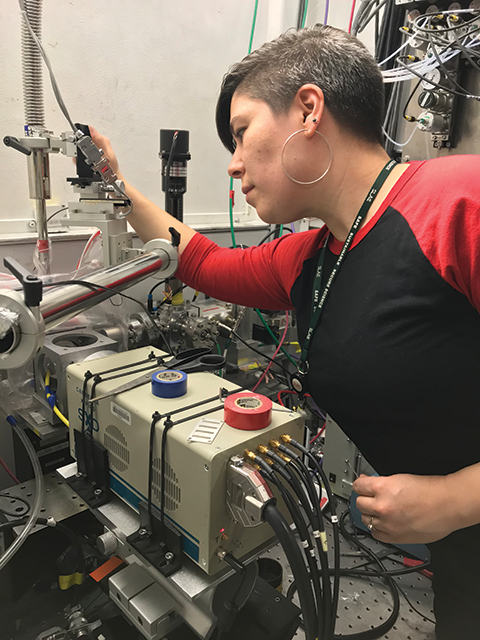

Thirteen years after starting at 23 with nothing but a GED and a vague dream, I became an assistant professor. I have a beautiful lab, great colleagues and amazing young minds to inspire. I have arrived. But what exactly does arrival mean? When do we truly feel we’ve made it? Why does everything I do not quite look like what my colleagues do? Why do we often feel so isolated and alone at work when everything is going so well?

My feeling of impostor syndrome is real and comes from a real place. As a long-closeted queer Latina who is the child of immigrants, is a first-generation college student and grew up broke, I find it intense and debilitating. Every day I am reminded that my journey and my worldviews are very different from my colleagues’. The only way to deal with such severe feelings of being an imposter is by watching our peers carefully, mimicking what we see and trying to produce work that is beyond what is asked so that no one will find out we’re faking.

For me, this watchful mimicry and perfectionism only worked for so long. A year into my dream tenure-track job, my alcohol intake increased to two, three and sometimes four drinks. Every. Single. Night. It is a dirty little secret that academics tend to abuse alcohol — for the social lubrication among strangers after a long conference session, for conviviality among institutional colleagues and as a so-called nightly treat in our pajamas during a 70-hour work week as a junior professor.

I began to unravel.

The biochemical effect of ethanol as a hormone — as a poison — is quite sinister. With the relief it provided, I could stop worrying at bedtime and drift to sleep. Yet it also disrupts sleep, and I woke in the middle of every night anxious and afraid of failing and of everything falling apart. During the workday, I was numb with withdrawal, anxious, depressed and tired; I thought longingly of my couch and a drink.

To be clear, I was doing my job and even thriving as viewed from the outside, but the negative cycle and pain continued in private. Under the haze of alcohol abuse and undiagnosed anxiety, I began to question why I was fighting so hard to succeed at a job that was so difficult for me when others in my cohort seemed to find it much easier and even fun. I fantasized about walking away from the torment of unbelonging.

Fortunately, my college supports a junior leave and sabbatical, and I decided to take it a year earlier than most. I visited a university far away to do sabbatical research. Living in an adorable studio apartment, I nipped the alcohol abuse in the bud by setting limits, self-reflecting and getting therapy. The alcohol was a coping mechanism for my anxiety, and I began to take a prescribed low dose of medication along with psychotherapy to help me process what an astronomically impossible journey to success I had achieved.

This intervention revived my quality of life, and it saved my career.

As I emerged from my endless cycle of self-doubt and anxiety, I also returned from sabbatical. I had cried in my therapist’s office the week before classes began, panicking about coming back to a job that I also knew I loved. She let me process these valid feelings, and I calmed down. Then she locked eyes with me and asked, “What is the worst thing that could happen if you made a real decision to start doing things your own way at work, Kelly?”

I was stopped in my tracks. In that emotionally charged moment, I accepted that I am different from most of my colleagues. I am a “diversity hire.” I don’t naturally do things in a normative academic way, and if I wanted to thrive, I needed my institution to assimilate to my worldview rather than the other way around. As institutions improve their unbiased hiring practices (and my hire was potent evidence of this), they must adapt to a changing way of designing and doing academic work.

I decided to be a visible example of what it looks like to exist and work unapologetically as an Other in the sciences and in academia at large.

So much has happened in the years that followed that moment, but a few key changes have allowed me truly to blossom. My classroom now is centered around the practice of radical vulnerability: When I stopped overpreparing so as to appear invincible in my lectures, I began to make small mistakes in front of my students and to allow them to do the same. I share stories about who I am as a real, fallible person. I do this on purpose — my students need to see that professors are human so they can see that despite their own imperfections, they too could be in front of the class someday.

This extended to my interactions with colleagues — I became very open about how I grew up, about my cultural differences and my view on work–life balance as focused on la vida. Most significantly, I took a tip from another Latinx scientist who was overbooked with demands for service and student meetings, which often occurs for a professor who is an underrepresented minority. I cleared one entire weekday each semester to work uninterrupted off campus. My other workdays are long and completely booked, but off campus I am able to write grants, run self-care errands, and spend time on scientific and academic pursuits that make me a better profé when I am in my office.

Some people may look at these behaviors and see a person who is messy, lazy and not fit to be in the academy. But to my delight, I have become proud of my science, teaching and outlook, and my colleagues cheer me on as I fly.

I never imagined I would feel like I belong despite being different among my amazing peers. While I wish I had sought help sooner, the hard journey was absolutely worth this moment of true arrival.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.