Mental illness after a Ph.D.

I have a Ph.D. and a debilitating mental illness. Too many people are astonished by the first portion of the previous sentence in light of the second.

I am writing this from the psychiatric ward where I am being treated yet again. My experiments have been graciously frozen down by my lab, but deadlines loom as the scientific enterprise rolls on unforgivingly. It does not appear I will be meeting the National Institutes of Health fellowship deadline this cycle.

I was diagnosed in 2015 during my junior year of undergrad with major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, and I later acquired a bulimia diagnosis in graduate school. I came back from studying abroad and suddenly I was sick with no explanation other than I was at the right age. I would not have sought treatment as soon as I did had it not been for my academic adviser, who immediately whisked me into counseling and psychiatry when I came to her thinking that what I was going through would be just a blip in my otherwise stellar college career.

Graduate school was very rocky for me. I went straight from undergrad into graduate school with no abatement of symptoms. I switched from a traditional wet lab experience to bioinformatics for safety reasons, having never coded a line in my life. Two mentors and a failed comprehensive exam later, I settled into a fantastic lab with an amazing mentor who worked with me and my accommodations, and with her support, I met all the requirements for the conferral of a Ph.D. while earning accolades along the way.

In the past eight years, I have gone through cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectal behavioral therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, and I was recommended for electroconvulsive therapy, which was framed as my last hope.

In treatment, both now and in the past, some mental health professionals seem unable to reconcile the fact that I have as much or more education than they have. After months of sessions, one therapist told me she assumed my vehement insistence that I had earned a Ph.D. was a grandiose delusion and my prestigious postdoctoral research fellowship involving a T32 in cancer epigenetics was an internship I had inflated.

Psychiatrists in inpatient psychiatric wards have pulled me aside to ask how someone so smart could “end up” in a place like this, grilled me on my research to check if I was lying, and told me that I was too smart to be in an inpatient ward with people whose lives were over and would amount to nothing.

I have never met another person in a Ph.D. program or with a doctorate in my hospitalizations, not to say there aren’t any. Many people have degrees, including graduate degrees, so it is an incredibly unfair assessment by the people we count on to take care of our health. Many times I have met other people my age who have had their dreams derailed by their illnesses, having dropped out of their programs due to worsening symptoms. Mental illness doesn’t discriminate but sometimes the providers do.

It’s not much better in academia. There my Ph.D. and education are recognized, but mental illness is absolutely taboo, and I occasionally find my fellow scientists throwing all logic and reason out the metaphorical window. After I was involuntarily admitted during my graduate studies, the renowned PI I was rotating with told me that if I just ate more protein none of this would have happened to me. Apparently, steak is the cure for treatment-resistant depression.

A few peers saw my medical and legally binding accommodations — such as having exams moved, more time for assignments and working from home — as excuses, and professors openly refused to make them on multiple occasions. One lab let me go after telling me that I had no hope of making it in science with such a severe illness.

In certain cases, I reported the awful things that were said to me but eventually gave up and just took them to heart when the administration told me, for example, that I was up against a tenured full professor and would never be believed.

I developed crippling imposter syndrome and convinced myself I deserved this treatment and that I wasn’t worthy of really anything. Call it stubbornness or stupidity, but I kept going, running on the fumes of relentless determination to be a geneticist that I had held as a dream since the eighth grade when I met my first Punnett square. I have also tried to channel this hurt into roles that put me in a position to advocate for those like me.

It has taken years to untangle my web of cognitive distortions aided by therapy, fantastic friends and devoted mentors. I am fortunate to work at my current institution, where empathy abounds and systematic changes are being proposed to our policies and training that advisers receive; these changes are based on feedback I have given and the navigation of my illnesses and treatments by the administration.

In no way am I saying that advisers should take on the role of mental health professionals, but flexibility and basic human kindness go so far. Systematic changes need to be made to the culture of science, how we train mentors to advise, and the biases we hold. It does not matter how many studies we publish about the mental health epidemic or our individual knowledge of the serotonin synthesis pathway if we don’t remember that the numbers are real people who are in our labs and programs. You can’t support me by being educated about the biology of my brain, but you can support me if you are educated about the functioning of my mind, the struggles I face, and taking the time to get to know me as a person.

It just doesn’t feel like the two aspects of myself can coexist. I can either be a scientist or mentally ill, but never a scientist with a mental illness in the same space.

It is incredibly scary to out myself here, and the ramifications of my decision to write this may come back to bite me, but I have no one to look to. My career path is shifting as I again find myself unable to sustain research in a wet lab in my postdoc, and I don’t know what to do. The decision about what happens to my future is mine and mine alone, but I have no clue how far I can go.

I don’t have role models to look to see how they have achieved their goals through their struggles, know what accommodations are even possible, or what types of fulfilling careers in science are out there for me. Shooting for the stars is an admirable dream but excludes the harsh realities of my limitations that I do need to acknowledge.

I know no one who has been in a psychiatric facility and is also a career scientist. So, I have written this hoping that I can be that for someone else.

My ultimate fear is that someone will read this and think to themselves “Why put in the effort?“ There are plenty of applicants or students who can work the 80-hour weeks with no accommodations or extra support. But we are worthy and can flourish too, and we have every right to be in the scientific space.

I can make an impact on the world with my science; I just need a little bit of flexibility. I know my story is not unique, but in sharing my experiences my goal is to help another scientist feel less alone, maybe help convince someone that they can indeed go to graduate school, or educate a PI on how to better support their postdocs.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

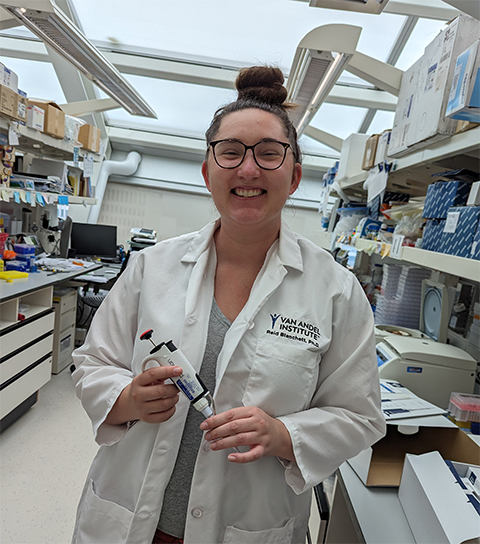

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.