Immigrants in the sandwich generation

“Can you join us for a lab dinner get-together?”

The simple email in my inbox triggered chaotic thoughts. My husband and I were invited to an evening of fun and laughter, but I had to apologetically decline. We live thousands of miles from our extended families, so it is difficult to find reliable childcare. Because it was a weekend, we needed to be available to talk to our parents back in India. And to top it off, we were buried in paperwork for a visa extension.

This single email made me think about how immigrant scientists get sandwiched between raising a family and taking care of parents, all while juggling a demanding career and visa complexities.

We are the sandwich generation of immigrant scientists; we must care for both older and younger family members at once across continents and oceans. When I was struggling to cope as a new parent isolated from family and friends, I found that adjusting to new work routines was a challenge.

In addition to day-to-day activities with a baby who seemed never to sleep, the stress of visa paperwork and job assignments left my husband and me tired. I felt the cultural stigma when I thought of leaving my child with a stranger. I tried explaining these difficulties to our families, but they were unable to understand. We were shaken when my father-in-law developed a new illness. We felt helpless, and the burden of not being able to care for our parents darkened our thoughts.

I was determined not to let my personal or professional life suffer, so I pushed harder and harder, trying to achieve it all. I felt physically and emotionally drained. While talking to my friends and family, I started to think how difficult it is for immigrants to build a career in science as well as raise a family and care for extended family. How could I do it? Had anyone ever succeeded?

My questions led me to two scientists with experiences much like mine.

Shared struggles

Sandra Gabelli, executive director of Discovery Chemistry and head of Protein and Structural Chemistry at Merck & Co., immigrated to the U.S. with her husband and two daughters in 1992. She is of Italian descent but was born and raised in Argentina, where she left behind a comfortable and familiar support system. Just like us, her family experienced a seismic cultural shift and the first few years in the U.S. were stressful. Like me, she struggled to find proper child care. These similarities made me realize that thousands of immigrant scientists face such struggles.

“Understanding how child care works here was difficult,” Gabelli told me. “Also, coming from Argentina I was clueless about the appropriate and safe hiring process for child care, and I almost ended up hiring the wrong person. In the end, I decided to take care of my girls at home while I was preparing for my graduate school admissions.”

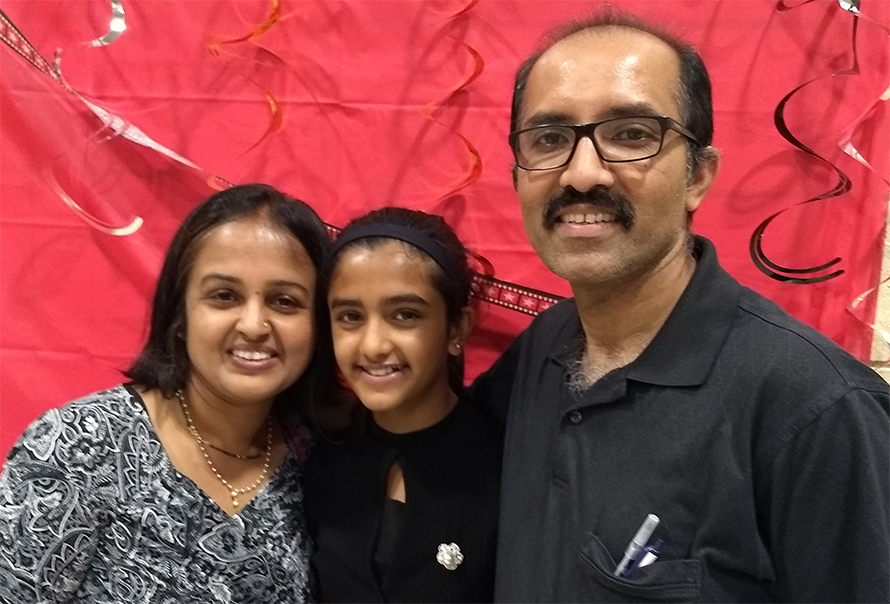

Immigration status dictates personal and professional life choices for many scientists, including Rajendra Upadhya, an assistant research professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at Duke University. He completed his Ph.D. at the University of Mysore, India, and came to the U.S. as a postdoctoral associate.

“After initially arriving on an H1B visa in 2004, I found myself confined by its limitations,” Upadhya said. “Changing fields or labs required my PI's approval, and visa extensions were stressful and expensive, detracting from my personal and professional life. Balancing work and family life was incredibly challenging, especially without any family members around.”

Upadhya’s situation eventually improved, but not without making sacrifices.

“Fortunately, when my daughter was born, I was in a supportive lab where I had the flexibility to work at any time, allowing me to manage both work and family responsibilities smoothly,” he said. “However, my wife and I made the decision not to have more children as we recognized it would hurt my research commitments and my family.”

Finding support

Every immigrant scientist experiences a learning curve, balancing a career and family. In a new environment, so culturally different from the ones we were raised in, mundane tasks seem difficult. We lack the luxury of calling on family for help. We struggle to care for our children and try to build a future in an unfamiliar land. We are unable to care for our aging parents when they are sick. We miss family functions when we can be together with all our relatives. We lose touch with childhood friends, and it can be challenging to talk to colleagues about personal issues. It is tough to keep going.

“My father passed away the week that I was taking my comprehensive exam,” Gabelli said. “During my Ph.D. and postdoc at Hopkins, I learned to adapt and that shaped me into who I am today.

“My friends here became aunts and uncles, and my dear neighbors went for ‘grandparent's day’ to my kid’s school. Friends would come to my rescue when I needed them to pick up my kids if I was sick at home. Attending a friend’s wedding became attending a family’s wedding. Following my passion for science with support from my new family enabled and empowered me as a mom.”

Not only do friends become family. Upadhya also stressed the importance of finding supportive academic mentors.

“As a scientist having a mentor who grants you ample freedom, ensuring you stay focused on your short- and long-term goals, is paramount,” he said. “But it is important to look for a mentor who not only guides your scientific endeavors but also is understanding of your family situation. With such mentors, the lab atmosphere is positive, helping build great friendships with colleagues who become your family away from family while you are making positive contributions to the scientific field.”

We all agree that it is important to acknowledge that you are not alone on this journey. Gabelli gave me my new mantra: “You may have a plan in life but be assured that life has a plan for you. Embrace it, appreciate the small joys, a good meal, a passionate discussion with your loved ones, a walk in the neighborhood while you talk with your family back home, and keep moving forward. In the end, it is these moments that will matter and be remembered as successes and not the struggles.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.