Science meets soccer: It’s all about passion

As Argentina celebrated its third World Cup championship and the entire planet was thrilled by 35-year-old Lionel Messi’s long-awaited historic conquest, I could not stop thinking that one billion people with diverse cultural backgrounds were all sitting in front of their screens to watch the final.

Throughout the game, our hearts raced — my smart watch indicated over 130 beats per minute for over two hours. And as the penalty shootout ended, tears of joy or desolation rolled down our cheeks.

I was born and raised in Argentina, so soccer (aka fútbol/football/futebol/calcio) runs through my veins. As a fan of Racing Club, a major Argentine team, I experienced the thrill of attending games each week throughout my youth. Still now, I watch every single game on my laptop — wearing my Racing Club jersey, of course — and I sometimes even fly to Buenos Aires to watch a final.

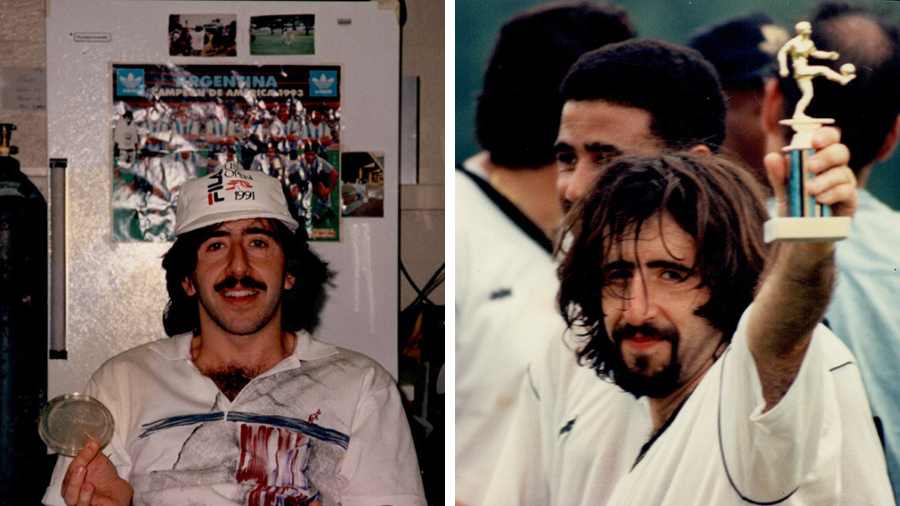

In my years as a postdoctoral fellow at the National Institutes of Health, Friday evening pick-up soccer games outside our building were almost mandatory, with postdocs from all over the world (as well as lab chiefs) relieving stress after a long week of hard work. Running an electrophoresis gel? No worries: just lower the voltage and you can play a longer game (and by the way, your Western blot bands will look sharper). For our NIH team, the joy of winning the county league in 1995 was comparable to having a paper accepted in a top-tier journal.

Passion — the energy coming from within in pursuit of your aspirations — is at the core of both sports and science.

As a postdoc, I would stay endless hours in the lab waiting for each scintillation vial to be read — and there were hundreds of vials sometimes. No way would I go home until the last vial was read and a graph was made. At times, reading the radioactivity counts could be as stressful as watching a World Cup match. I’d find myself loudly celebrating an exciting result as if I were in a soccer stadium after a last-minute goal in extra time: “Yes! Yes! Yes! There was 32P incorporation! My kinase is active!”

Forty-eight hours in the lab, mostly in the cold room, were not in vain.

The opposite was also sometimes true. I might leave the lab in total despair if the protein turned out to be dead. How could I have forgotten to add glycerol after the last purification step?

In science, passion gave me the resilience to overcome frustration and build a thick skin.

Nowadays, I often hear my fellow PIs talk about the struggle to recruit enthusiastic trainees who have a hunger for scientific inquiry. As one colleague asked, “Is passion in science evaporating in the young?”

While I hesitate to agree, I recognize that the landscape of scientific careers has become exceedingly competitive. The rough path to get data published and the hurdles to gain grant funding are likely dissuading the upcoming generation of scientists in academia. I hear graduate students and postdocs say to each other, “I’m not sure I want to spend my life writing grants knowing that the odds to get them is so low.”

I wouldn’t argue with this statement. There’s no right or wrong here. But as PIs we should be committed to creating an environment that nurtures enthusiasm in our trainees, where they develop a backbone of motivation for their scientific undertakings.

I have seen many of my former trainees pursue successful careers and take leadership positions, largely driven by their pure enjoyment of science. Several former postdocs now run their own labs at academic institutions either in the US or abroad. A common denominator is their dedication to hard work, supplemented by an inner hankering to unearth the unknown and a craving for breakthroughs. Nearly 20 years after one of my postdocs left the lab, I received an emotional email, thanking me for instilling in her the passion for discovery, as she became the new scientific director of her institute abroad. “Not at all” I replied. “Hard work and dedication pay off.”

If we had a “P index,” I’d predict it most likely positively correlates with success in science.

As in sports, success in science is not only about intrinsic talent or natural abilities. It requires genuine commitment, eagerness to learn, discipline, teamwork — and truthfully, sometimes a bit of luck. Learning from errors and failed experiments — sound familiar? — together with dedicated troubleshooting as a systematic approach to problem solving, is key for overcoming any technical issues you encounter in the lab. Just like practicing penalty kicks, intensive training and endurance may lead you to the next round in your research.

When Lionel Messi raised the World Cup trophy, that action capped years of hard work, sacrifice and perseverance, the fruit of a pure passion to pursue a dream. It embodied the ability of a team to fearlessly thrive through fierce competition.

My best advice: Work hard and play hard. Like Messi, you can become the hero of your scientific journey. It’s all about passion.

(To learn more about what the author does when he's not playing soccer, visit his lab's webpage.)

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.