How I barbecued myself with stress ... and recovered

Graduate school for scientists is an apprenticeship. This means learning by doing, and it frequently means learning through failure. Grad students are new to the game but expected to make the next greatest scientific advance. They rarely have enough time to learn how to do something before actually doing it. As a result, when students get unexpected results, it’s unclear whether they made a mistake or the results are real. This constant uncertainty can cause students to worry and doubt their achievements continually.

To make matters worse, the culture in most labs is to work all the time, certainly more than the fair labor standard 40-hour week. Grad students are paid a meager salary that usually comes with a noncompete clause. Other professional programs don’t pay students, but they compensate with regimented program length and career prospects. The Ph.D. has flexibility in those respects, but the cost is ambiguity in how long it takes to finish and what nontraditional career one should take to be employable afterward. So Ph.D. students typically play a dangerous game of high-stakes, high-pressure roulette full of ambiguity and failure, making for a dangerous concoction of prolonged stress.In high school and college, I learned to thrive under pressure by being self-critical and pushing hard. I excelled in my rigorous class schedule and landed promotions in my part-time jobs. But I let graduate school turn my formula for success into unhealthy self-doubt and self-loathing.

After all, scientists are skeptics; everything we know and learn is uncertain. For me this meant retroactively questioning whether I had done everything right and hating myself for every mistake. Being self-critical makes me a meticulous (and good) scientist; I try my best during experiments and check my math afterward, resulting in reliable work. But there’s a fine line between being your own best critic and having crippling self-doubt. I knew I was past the line when I drove through a nearly empty intersection one night and questioned whether I had just run a red light.

Constant anxiety, self-doubt and worry harmed both my mental and my physical health. I couldn’t eat a meal without hearing fireworks in my stomach and being in so much pain I almost couldn’t walk.

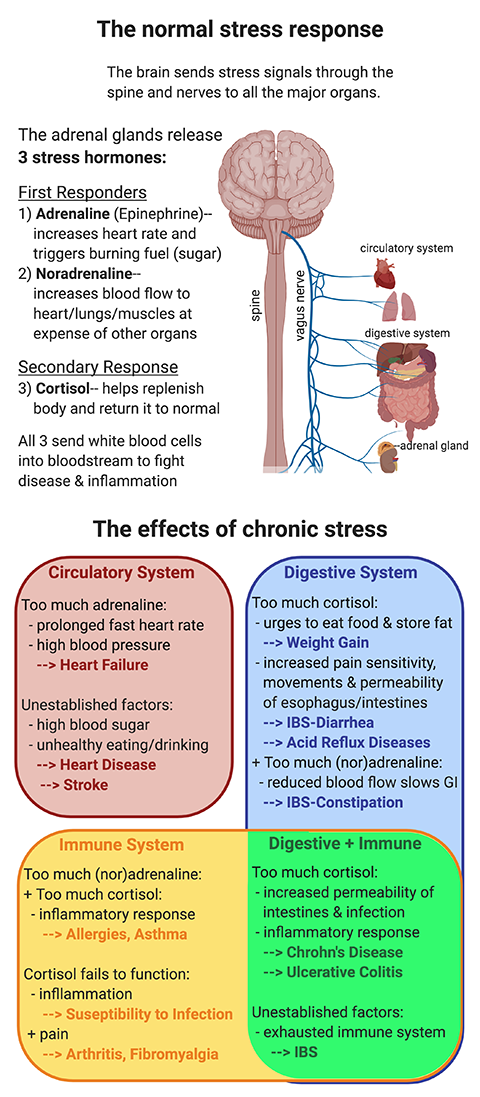

There’s serious science behind this; long-term stress has detrimental effects on many of our major organs. My stress in overdrive was turning up the heat on my internal organs and frying them with a steady influx of stress hormones.

.png)

The stress response is effective for the body’s flight-or-fight mechanism when it helps a person run fast (top half of infographic), pay attention and take care of immediate business. But when a body is always in fight-or-flight mode, stress hormones continually tell the heart to work harder, the immune system to be on the lookout, and the digestive system to wait or replenish quickly so as to be ready for the next battle. The neurotransmitters serotonin and dopamine also can contribute to barbecuing the body. Continued stress responses can have dire effects on the cardiovascular, immune and digestive systems (among others) and may cause permanent damage (bottom of infographic).

The key to rising above this abyss of stress is retraining the brain to handle stress in a more healthy way. I spent a lot of time in therapy retraining my brain. Below I share what worked for me. Everyone is different, and these five tips cannot replace finding a unique path through individualized therapy. Anyone faced with physical ailments due to stress should seek treatment for both body and mind.

Five tips to manage stress

Graduate school is hard enough. God forbid something happens in your personal life to push you off the cliff into anxiety and depression. Here are my five go-to strategies for climbing out of the pit of despair and not falling back in.

1) Ride the tide. After a group therapy class on how to manage anxiety, I walked away better equipped to weather storms. It required a healthy dose of mindfulness and kindness, mostly toward myself. I’m often stressed because I overthink my reactions (being mad that I feel mad about something or being frustrated with myself for making a mistake). In these situations, I try to practice willingness — giving myself the ability to notice my reactions from a distance (mindfulness) and giving myself permission to feel however I feel (kindness).I use my critical side to observe and take notes while also allowing myself to make mistakes and have feelings (even negative ones). This is not a shoulda–coulda–woulda approach but rather a way to focus my critical nature on learning in the moment and taking everything in stride. It’s like when I tell a friend about something upsetting and she agrees she would be upset too. But I’m my own best friend.

I let myself feel whatever I’ve felt and let it pass in its own time — like riding a wave. I feel mad about an injustice or sad about the consequences of a mistake. This shifts the spotlight toward accepting the harsh truths of reality: Life’s not fair, bad things happen and I’m not perfect. As a result, I’m not fighting myself; I’m empathizing with myself, being more of a bystander to my own traumas. I can evaluate critically what triggers my feelings and how I respond to those triggers. This gives me the power to think of a better response the next time I’m faced with a similar trigger.

2) Accept that you always will have things to do. My favorite self-help book is “Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff and It’s All Small Stuff” by Richard Carlson. I flip through its short chapters for inspiration. One of my favorites is Chapter 6: “Remind Yourself that When You Die, Your ‘In Basket’ Won’t be Empty.” I’m a great list-maker, and this chapter reminds me that I never will finish a list. Or for every list I finish, I’ll make a couple more. I still feel free to make lists, but I know it’s impossible to get it all done. I’ve learned to prioritize; sometimes this requires a hard look in the mirror to decide what I value most. As a result, I don’t beat myself up (as much) when my lower priorities don’t get done. And when I check something off my list, I try to enjoy it for a moment.

3) Stop multitasking. Most of my stress comes from trying to do too much with not enough time. I’m a normal person with limits to my average-sized brain, and I’m now comfortable with that (thanks to step 1). Instead I do things in bulk. When I have a lot of priorities, I pick the thing that seems easiest, and then I do a bunch of it.

If I need to respond to an email, I respond to other emails while I’m at it. Or if my brain is already trying to figure out how to do my next experiment, I let it. Then I keep the momentum going by planning an experiment to follow it. If I’m in the mood to get up and do something, I do the experiment, and then I make up some buffers ahead of time. For extremely time-intensive work such as molecular biology or protein purifications, I try to make multiples at one time. This method may slow me down initially, but once I finish the task at hand, I typically get results from two or more.

4) Learn when to say no. Healing takes time. Everyone knows this is true for the flu or a broken leg, but fewer people accept it for recovering from mental illness. Mental recovery is different for everyone and always a continual process. I’m an introvert, so I need to step back from whatever is causing me stress and breathe a bit. My mantra has become, “Under-promise and over-deliver.”

I have to gauge my own stress level, know the cost associated with a specific task (estimating time and multiplying by three is key), and weigh the costs and benefits. If I can’t estimate my stress or the timing for a task, I’m probably already overstressed and beginning to shut down. Then I know I need to say no. If I have a hard time saying no outright, I’ve perfected the lawyer version: “I’ll try to fit it in, but I’m not promising …” Even with someone who is unreceptive to hearing no, expressing reservations can open a dialogue about how to reduce my burden.

5) Channel a character. To train myself to react differently to stressful situations, I pretend to be a TV, movie or book character. I channel Phoebe from “Friends.” Phoebe sees crappy situations for what they are, calls them out and moves on without a beat. In one episode, she finds out her sister is a porn star using Phoebe’s name in the movies. Phoebe tries talking to her sister, but her sister refuses to change her behavior. So Phoebe goes to the porn company to change the address where they mail her paychecks. And she doesn’t look back.

I also like to channel Luna from the Harry Potter series. I love the moment Harry finds her walking barefoot as she tends some mythical creatures. She has suspicions about who stole all her shoes, but she seems unbothered and rises above the annoyance.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.