Seeing is believing

Some 17,000 years ago, on a cave wall in Spain, a person drew a picture of a mammoth with a dark shadow where the animal's heart would be. Some believe this is the earliest example of anatomical drawing.

Today's science illustrators are still expected to know where to place organs and other major structures, but they're also expected to convey the intricacies of living beings' insides — down to the molecular level. Doing that well requires specialized knowledge, often acquired formally.

We spoke to three science illustrators about their career paths.

Academic beginnings

Luciana Giono's family has interests in architecture, music and graphic design, but she ended up studying science, completing the equivalent of U.S. bachelor's and master's degrees in biological sciences at the University of Buenos Aires in Argentina. The school's architecture/design and science departments were in two almost identical buildings next to each other on campus.

"I used to joke that I went to the wrong building," Giono said. She did graduate work at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, with research focused on gene expression, cell cycle and DNA damage response. While studying for her Ph.D. qualifying exam, she made a big figure summarizing all the cell cycle details she had learned — and realized how much people rely on diagrams and visuals to communicate scientific knowledge efficiently.

Kate Patterson always has enjoyed doing art but said she put it aside to study veterinary science. During her undergraduate studies at the University of Sydney in Australia, she was intrigued to learn that certain breeds of dogs are prone to specific types of cancer. In practice, she treated many boxers with mast cell tumors (a type of skin cancer) and German shepherds with hemangiosarcoma (cancer arising from cells in blood vessels). Thinking this must have a genetic basis that also might apply to human cancer, she enrolled for a Ph.D. at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research at the University of New South Wales, where she studied how a dual specificity phosphatase called DUSP23 affects ovarian cancer progression.

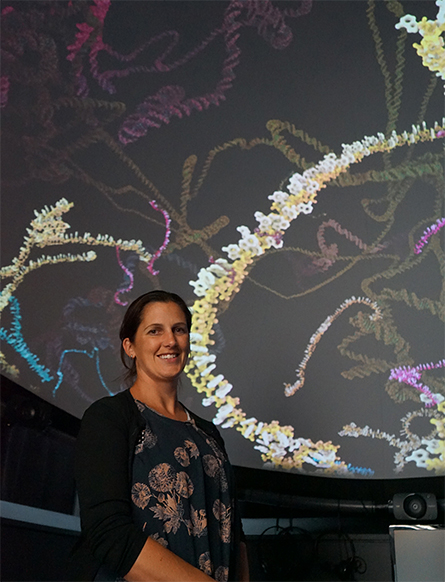

Cell Observatory.

As a graduate student, Patterson enjoyed making graphs and figures to communicate her work clearly, and she realized this was not something that came easily to everybody. "A component of being a scientist is to be able to communicate your work clearly," she said. "I was one of the weird ones that really enjoyed writing up my thesis and making posters."

Radhika Patnala's mother was an interior designer. "The world of art and design was quite prevalent in my household as I was growing up," Patnala said, "so I developed an interest in fine arts, design concepts and design software from a very young age, even before I was exposed to the wonderful world of science and biology."

Patnala completed her bachelor's and master's degrees in biotechnology from Gandhi Institute of Technology and Management in India and the Australian National University, respectively, and then earned a Ph.D. in neurosciences from the National University of Singapore. "My research was focused on neuroinflammation and epigenetics in the context of a fascinating cell type called microglia," she said. "I did a lot of microscopy during my Ph.D., which exposed me to the visual beauty inherent in life science."

Turning an interest into a career

As an extension for their love for arts in science, both Patterson and Giono eventually found themselves making figures for colleagues' papers and posters. "I really enjoy making them, which means I take the time to do it carefully, both in terms of content and looks," Giono said.

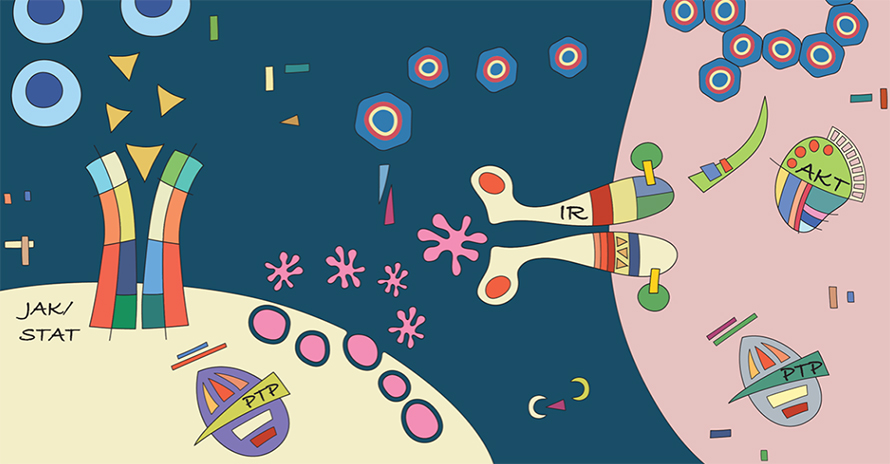

She worked as a career investigator and teaching assistant for many years and then began asking journals if they would be interested in having someone dedicated to figure production. Her very first work for a Journal of Biological Chemistry review article consisted of illustrations showing ways of studying RNA–protein interactions at the molecular level. Now a freelance illustrator, for several years she has prepared many cover illustrations and figures for JBC and the Journal of Lipid Research. Her illustrations also have been on the covers of other journals including Cell, Nucleic Acids Research and the Journal of Hepatology.

Patterson took an equally indirect route to becoming a science animator. She started out working as a science writer at the National Breast Cancer Foundation and a freelance illustrator through her website, MediPics and Prose. "In Australia, there is no formal training to become a science illustrator, so there aren't many people in this area," she said.

About a decade ago, the Australian government funded an animation program as part of "VizbiPlus — visualizing the future of biomedicine," a project to create a more "scientifically engaged Australia." Patterson was one of the three people who received the grant; they created public-facing animations from scientific findings across Australian institutions to raise general awareness about science and medicine. This program, which she describes as "awe-inspiring," helped Patterson make the transition from illustrator to animator.

Her very first animated short documentary, called "Cancer Is Not One Disease," showed the complexities of the disease based on the experience of a patient living with pancreatic cancer.

She has worked for the past decade as a visual illustrator at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research, putting complex scientific concepts and discoveries into the form of visual stories that scientists can utilize and also that nonscientists can understand. She is now the institute's senior visual science communications officer — a title she said was invented upon her appointment, because she was the first person to do such work there.

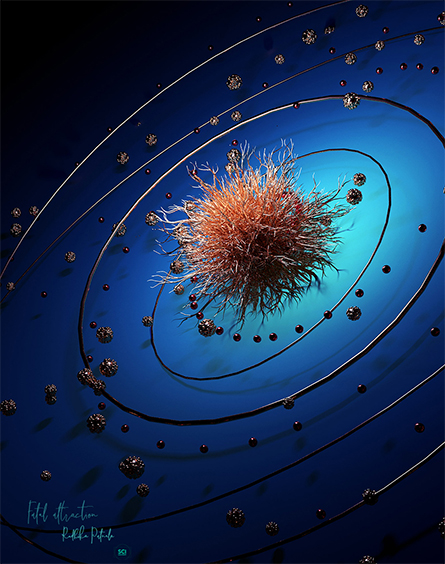

by Radhika Patnala exploring ideas about COVID-19 and how the world deals with it.

During Patnala's doctoral training, arts and aesthetics were an integral part of the overall skill set she developed, along with the realization that science communication is a large part of doing science as we know it. "Eventually, the two aspects came together to dictate what I am going to do as a next step" she said.

Soon after completing her Ph.D., Patnala moved to Germany to be with family and started a creative agency, Sci-Illustrate, to explore the use of scientific illustrations and visuals to aid in science communication. Since then, her science-inspired art has been featured on covers of Cell and JBC and the covers of Nature Reviews Neurology for all of 2020. Based in Munich, Sci-Illustrate now provides design services such as scientific illustrations, motion graphics and data visualization to biotech companies, organizations and research labs in health care and life sciences. A passion project at Sci-Illustrate is the Women in Science initiative which, Patnala said, highlights "the personal journeys of women in science from India and around the world over the past two years through art and words."

A science background helps

Although their careers took them away from research, Patnala, Giono and Paterson agree that their years at the bench were not wasted but actually helped them along the way.

"I would think my science background is actually my greatest asset, or at least one of them," Giono said. Years of learning science as well as critical reading, discussion and writing of scientific papers gave her the ability to grasp concepts and find the information she needs for her illustrations. She also is able to point out errors in figures and propose alternatives.

JBC publishes papers on a wide variety of topics and reaches a large audience. Giono might not be an expert in all the topics, but she can place herself in the readers' shoes and find the best way to communicate the scientific knowledge through her illustrations.

Patterson said her veterinary science training helps her understand what pieces of information are necessary to communicate a message clearly to the audience. Pet owners often do not have detailed scientific knowledge, so she learned to simplify complex concepts to help them understand their animals' diseases.

But even with talent and knowledge, science illustration — like all career paths — has its challenges.

When Patnala went to set up her company in Munich, she found that all the official documents were in German, a language she does not read or speak. She said she still relies on her husband to help her out with such formalities.

During Patterson's gradual transition from postdoc to science illustrator, learning how to use the powerful animation software was initially a challenge. To overcome these roadblocks, she attended conferences and talks by practitioners in the field of biomedical animation and accessed online courses and tutorials to help learn how to use the software effectively.

Science illustration vs. science art

Science illustration is a broad term, Giono said, that encompasses everything from "'a boxes and arrows' kind of diagram to an elaborate 3D human body illustration, to even an illustration for an editorial or news article."

A science illustration caters to the technical needs of the customer, she explained, while science art allows for some poetic license. For example, a figure model summarizing results in a research article is a science illustration, while a journal cover could be science art.

of her #Futurepopart: Lifescience Edition art series.

When a science illustrator receives an assignment, Patnala said, the person needs to be careful that the depiction is scientifically accurate so it communicates the necessary information. Science art, on the other hand, can be influenced by the artist's perception of a scientific concept rather than purely based on factually correct information.

Creating an illustration requires communication with clients to understand what they want, Giono said, and catering to clients' specific needs sometimes requires compromise. Nevertheless, she enjoys the challenge of coming up with innovative ways of presenting a scientific report or idea on journal covers.

"Then the greater challenge comes when you send your image to the author and are waiting to see if they will like it or hate it," she said.

Raising awareness through advances in tech

Whether creating art or literal illustration, professionals use tools such as Adobe Illustrator and Adobe Photoshop for static illustrations. Many graphics can be directly created with such software, but Giono said she sometimes prefers drawing by hand, scanning the art and coloring it using Photoshop, especially for journal cover images.

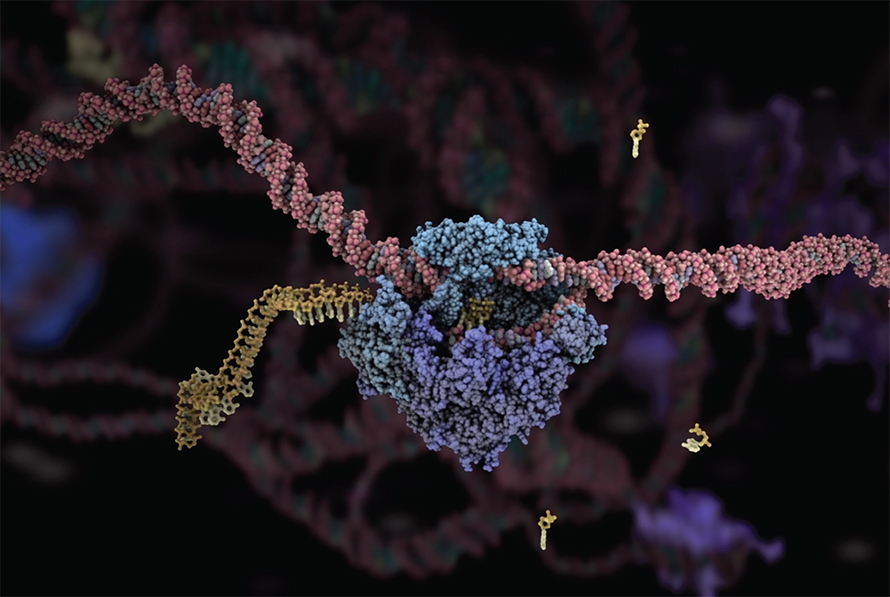

Patterson uses the 3D animation software Autodesk Maya to create animations. When animating a protein that has a known crystal structure, she imports Protein Data Bank files into a plug-in called Molecular Maya. The plug-in gives her the 3D coordinates of all the atoms in the molecule, and using those coordinates she can animate the molecule in its entirety. For the past year, Patterson has been involved in creating a virtual reality experience at the Garvan Institute. They have built an immersive visualization dome called the Cell Observatory, where visitors are transported to the inside of a cell. Animations of processes such as DNA transcription appear on the curved ceiling while scientists explain what specific proteins do in the process.

With the help of hand-held controllers and a head-mounted display such as the Oculus Quest, visitors can move the RNA polymerase onto the DNA strand to make RNA. During a Christmas event, the Garvan staff set up an outdoor booth for a similar virtual reality experience, Patterson said, and people were playing with molecules on the street using the headset and controllers.

With technologies such as Google Cardboard, people can use their phones to visualize scientific processes in three dimensions and 360 degrees. Such experiences leave a longer-lasting impression than reading about the same process in textbooks, Patterson said, or even seeing it as a movie.

Scientific articles and reviews are read by a niche audience, but the same findings presented in the form of a diagram or a movie can be understood by a broader community. Using their skills to bring science to the masses in this way serves as a big motivation for science illustrators. Patnala's favorite projects include "#Futurepopart," a series of 30 skateboards depicting 30 different concepts in life sciences, and a recent 10-part series of illustrations called "The COVID Dreams." With so much energy and passion invested in her work, "I end up liking most of my creations," she said.

"Science is about communication," Giono said, "and the central role of visuals in that communication cannot be stressed enough."

For many people, the biggest barrier to understanding the basic scientific concepts that govern life is a fear of asking questions. Nonscientists are intimidated by jargon. According to Patterson, public activities such as the cell observatory help break down these barriers and initiate conversations. The Garvan Institute encourages school trips so children can be exposed to the fun in science. In addition, Patterson has worked with teachers to find ways to include illustrations and animation in their lessons.

the nuances and complexities of lipoprotein clearance."

'It's a lot of fun'

While science illustration can be a creatively satisfying job, there are roadblocks to making it a career. Few full-time positions are available. It is often a freelancer's job, so finance becomes a confounding factor and there is not a set career path.

Both Patnala and Patterson advise beginners to build their portfolios while doing something that makes them financially independent and developing skills required to make illustration a full-time job. It is also possible to enroll in a full-time course offered by various online platforms and some institutions to learn the skills of illustration and then seek employment. In fact, Patnala's company offers an intensive science illustration workshop for life scientists and health care professionals.

"You've got to find your own adventure and create your own job because they don't get advertised very often," Patterson said, but whatever the challenges, "It's a lot of fun and you should do it."

SEE MORE OF THEIR WORK

Luciana Giono https://www.behance.net/lugiono

Kate Patterson https://www.garvan.org.au/people/katpat, https://medipicsandprose.com.au/

Radhika Patnala https://www.sci-illustrate.com/

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Cooking up science engagement, a fermentation experiment

By blending hands-on cooking with scientific experimentation, a study from a team at North Carolina State University demonstrates how culinary creation can spark scientific discovery and deepen public engagement with researchers.

Upcoming opportunities

ASBMB's PROLAB award helps graduate students and postdoctoral fellows spend up to six months in U.S. or Canadian labs.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.