A matter of degree

Growing up in Sicily Island, Louisiana, Zerick Dunbar loved his high school math and biology courses. He went to Tulane University, some 200 miles from home, to study biomedical engineering and landed a job after college that was in a lab — he worked in quality assurance at a petroleum company — but didn’t fit his interest in biology. So he returned to Tulane after a few years to seek a master’s degree, hoping to find work at a medical device company.

As he worked in the lab alongside Ph.D. students, Dunbar said, his ideas about what could be done with his degree changed. Now he’s a third-year doctoral student at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, studying variations between natural killer cells across tissues. He has become interested in entrepreneurship and hopes to pursue a career in biotechnology, eventually launching his own ventures after graduation.

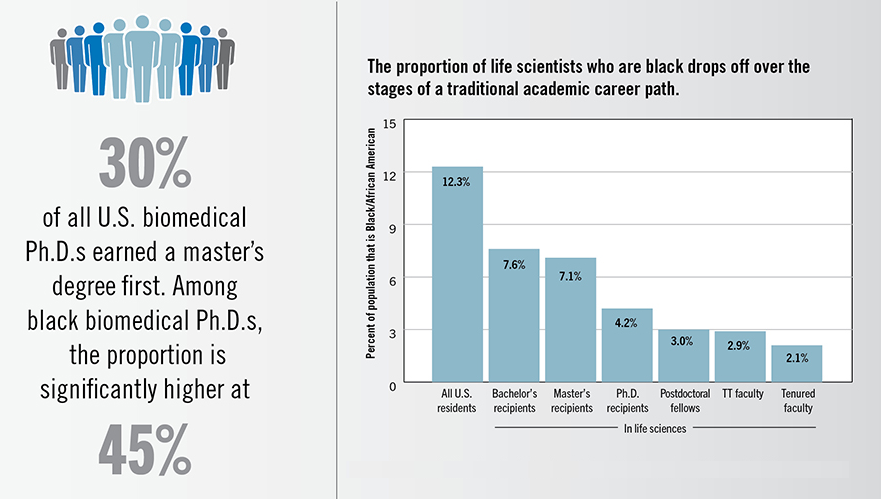

About 30% of Americans who earned a Ph.D. in the biological and biomedical sciences in 2017 had, like Dunbar, earned a master’s degree before they enrolled in their doctoral programs. Among students who identify as black or African American, that proportion is significantly higher: closer to 45%. A master’s degree can be an important intermediate step for students who at first are not competitive for admission to doctoral programs. At the same time, it can be costly, and a bad experience could derail promising researchers at an early stage.

Knowledge of this disparity varied among experts on diversity and inclusion in science interviewed for this story. Some consider it common knowledge. Others expressed surprise and even skepticism.

Kenneth Gibbs, a program officer who directs training programs at the National Institute for General Medical Sciences, or NIGMS, said, “We need more research. That’s not just a pat answer; we really need to understand better why individuals make the choices they do leading up to entering a Ph.D. program.

“A master’s is not a bad degree. A master’s en route to a Ph.D. is not a bad thing. It becomes a bad thing if there is some differential, systemic issue that is causing this different outcome — that is, if admissions committees require more from black candidates than others.”

Does such a systemic issue exist? Policymakers don’t know for sure, but they point to several well-documented educational disparities that may make it likely for black Ph.D. recipients to enter graduate school with more education on their CVs than their peers.

First in the family

“Black scientists live as black people, and black people in America have different lived experiences than other groups,” Gibbs said. One part of that mosaic is a legacy of limited access to education, meaning that many students of color are the first in their families to pursue college or postgraduate degrees.

Zerick Dunbar is an example. “No one from where I’m from has ever gotten a Ph.D.,” he said. “Maybe one guy back in the ’50s or ’60s.” As a consequence, his path to graduate school was his to determine on his own.

Compared with many fields, including Dunbar’s undergraduate major of engineering, biology is unusual in that students don’t need to earn a master’s degree before applying to doctoral programs. Students who don’t have a family member or mentor with insider knowledge may not realize that.

Alyssa Cobbs, who finished her Ph.D. at Morehouse School of Medicine in 2019, started considering a research career as a senior in college, rethinking her original interest in pharmacy school. While attending the Annual Biomedical Research Conference for Minority Students, widely known as ABRCMS, she learned that she could apply for a funded Ph.D. program even without a master’s degree in hand. The conference happened in November; Cobbs rushed to take the GRE graduate school entrance exam and wrote as many applications as she could finish before the December deadlines.

According to Cobbs, throughout graduate school, younger students would ask about where she earned her master’s degree and were surprised when she said she didn’t have one. Now her younger brothers and sisters are expressing interest in becoming scientists, and she looks forward to talking them through the process. “You know what you see,” Cobbs said. “If you’re never exposed to it, you don’t know how to go about it.”

Plenty of students are never exposed to the particulars of biomedical higher education. According to Avery August, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute professor of immunology and vice provost for academic affairs at Cornell University, some of the undergraduate students he counsels are “quite surprised that you can, so to speak, skip the master’s degree. … The other really interesting thing is that many students still don’t appreciate that during the process of getting a Ph.D., you are supported financially.”

Historically black colleges and universities

Students from prominent HBCUs are courted by many graduate programs, but some faculty at research universities lack knowledge of these institutions.

Read morePaying out of pocket

The overwhelming majority of Ph.D. students in biological and biomedical sciences, some 95%, are supported by grants that cover both tuition and living expenses. In contrast, paying for a master’s degree in the field most often falls on students. While about one-third of students join a funded program or land research or teaching assistantships, the majority of master’s degrees in biomedical sciences are financed by loans or out of pocket.

Taylor Carmon took out student loans to finance his master’s degree in food science at Alabama A&M University, a historically black university in Huntsville. He developed an interest in nutrition while reading up on diabetes and high cholesterol to help some relatives manage their diagnoses. That interest evolved into a college major and, eventually, a master’s program.

Carmon said he chose Alabama A&M strategically. All of his prior education was in majority-white institutions.

“I decided that maybe I should look at HBCUs to get some diversity in my education. Just in case I didn’t get tuition assistance, I decided to stay in Alabama.” That narrowed the selection down to two programs, one of which he eventually joined.

The decision worked out for his scientific education. “My current adviser just picked me out of the crowd to start talking to me about molecular genetics,” he said. “He got me interested in his research area by bringing me into the lab, talking to me about the different genes involved in lipid synthesis and how characterizing those genes could help people better understand certain diseases.”

Almost three years later, Carmon has traveled to conferences to present research he did as a master’s student and is building on that work as he pursues a Ph.D. in his adviser’s lab.

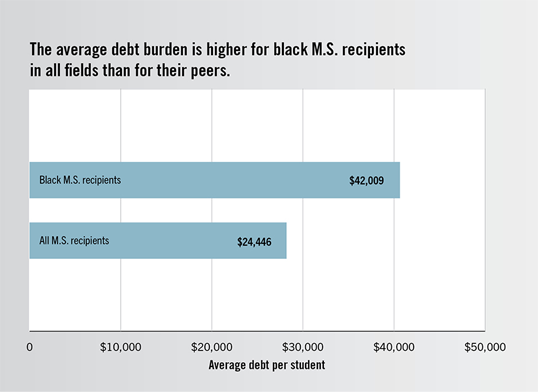

But the master’s, which was not funded, was costly; even for an Alabama resident, tuition for a year in the program is about $9,000, excluding living expenses. Across academic fields, according to the National Center for Education Statistics’ Postsecondary Student Aid Survey, 81% of black M.S. graduates carry debt related to their master’s degrees, compared with 56% of all M.S. graduates. Master’s recipients who are black carry, on average, almost twice as much debt as students in general.

Carmon is paid a stipend, but even now, neither his adviser nor his department is able to cover his tuition as a doctoral student researcher.

“That’s the downfall of choosing an HBCU; they may not have the funding to pay for your education,” Carmon said. “I know it’s a disadvantage to me, because right now, I’m paying out of pocket. I chose to stay here over leaving … because I know the research in the lab, I know what’s going on, I’m independent. I don’t have to start over from scratch.”

Carmon expects to graduate in three or four years. He said he and other students at Alabama A&M hope their department will land a grant sometime soon to cover tuition. In the meantime, he’s racking up debt.

Time in the lab

When Natasha Brooks was an undergraduate at Penn State with an interest in biochemistry in the early 2000s, she initially imagined a job in forensic science. A fan of the television show “CSI,” she wanted to use her lab skills to solve crimes.

After her goal shifted to biomedical research, Brooks said, applying for a master’s program seemed like the logical next step. She mentioned the plan to her research adviser, who told her, “‘No, you need to just apply to Ph.D. programs.’ He didn’t feel that I needed to take the intermediate step.”

Brooks had worked in the lab every summer since her freshman year, so the adviser was confident that she would be a strong graduate researcher. And he was right; Brooks was accepted to the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston for a Ph.D. in biochemistry and molecular biology, which she defended in 2012. She now works as a medical writer.

“The people who seemed to be more successful in the lab weren’t the people who had the highest GPA and GRE scores,” Brooks said about her fellow graduate students. “They were the people who actually had lab experience. I think that’s a good predictor of the outcomes.”

Kimberly Griffin, an associate professor of student affairs at the University of Maryland, confirmed this impression. Admissions committees, she said, “think quite critically about research experience and who you’ve had the opportunity to work with prior to entering your Ph.D. program.”

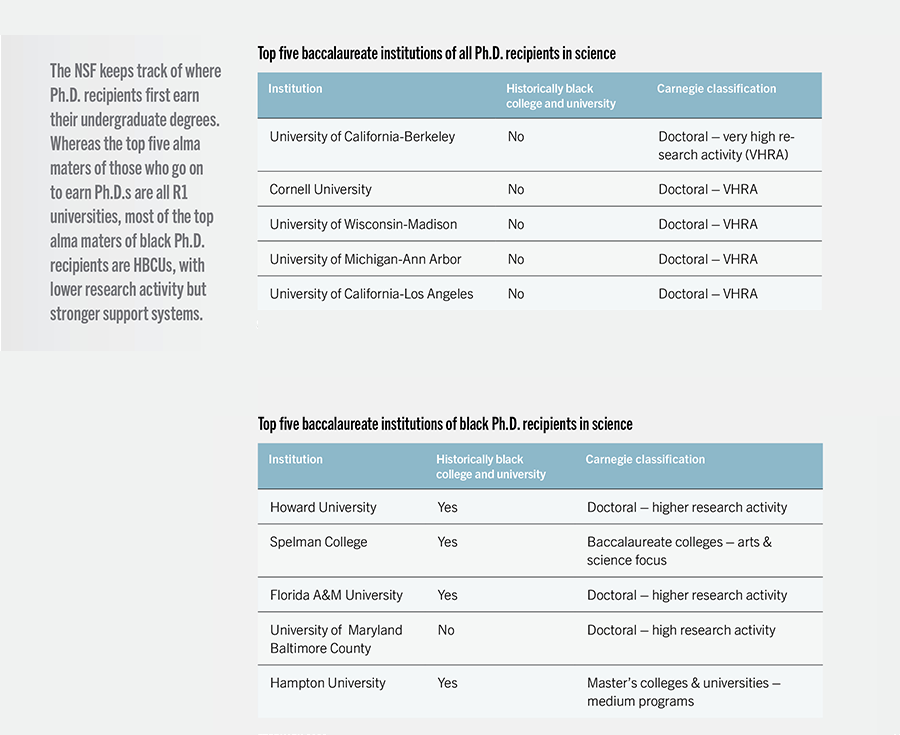

All five of the top institutions where Ph.D. recipients earned their bachelor’s degrees are classified as R1 universities by the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, meaning that they have very high research activity. In contrast, the historically black colleges and universities that educated the most black students who later earned Ph.D.s have smaller research programs and graduate populations.

“HBCUs are wonderful institutions and are doing great work in terms of giving students the skills or the confidence they need to want to pursue graduate education,” Griffin said. But “they may not have the lab facilities that would allow students to get the depth of experience doing lab-based science that other students might have.”

For students whose degrees are from schools with less robust research activity, a master’s degree may be a substitute for undergraduate research experience.

Kenneth Gibbs at the NIGMS thinks about it in terms of his own educational path. “If you’re at Stanford, you have different levels of research available to you than at (the University of Maryland, Baltimore County). Those are two places that I went to school. I took advantage of what was available to me — but sometimes, at Stanford, Ph.D. applicants were judged by the Stanford standard.”

Admissions committees, he said, would do well to consider how much access an applicant has had to research labs.

Gibbs often speaks to trainees — at various academic stages — whom he considers ready for a next career step by most metrics. Sometimes he finds that they don’t feel ready. He suspects that the hypercompetitive culture of academia affects different groups to different degrees.

“As a professional black person, it’s not uncommon to hear you have to be twice as good to get the same results as people from majority backgrounds,” Gibbs said. That, he said, might motivate students to rack up extra credentials before applying to start a Ph.D.

In 1996, Richard McGee, a professor of medical education and associate dean of professional development at Northwestern University’s medical school, started a postbaccalaureate program for students who want to spend more time in the lab before committing to a doctoral degree. The model has caught on and been adopted as the Postbaccalaureate Research Education Program at campuses across the country. McGee says he was motivated by having variations on the same conversation over and over at undergraduate research conferences for minority students.

“It wasn’t an academic deficit,” he emphasized. “It was ‘I’m just not ready yet … I want to get more experience in research so I feel like I know what I’m getting myself in for.’”

For students he has worked with, McGee said, taking time to be sure of the decision to pursue a Ph.D. often has been positive. Whether the intermediate step is a master’s degree or another training model, “Your confidence, your self-image, your self-efficacy; all this stuff is going to be bolstered at each step along the way (as) you get more data to counter the narrative that ‘I don’t belong here.’”

Bridges to the doctorate

Like postbaccalaureate programs, some master's programs are designed to help students considering doctorates.

Read moreThe GRE

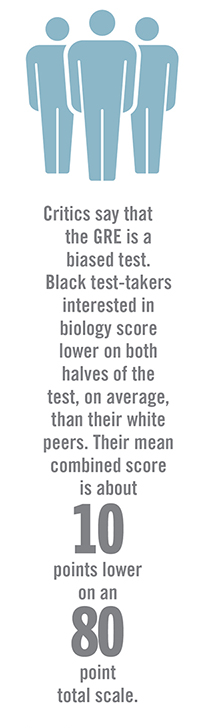

Along with research experience, recommendation letters and undergraduate grades, the GRE is an important factor in graduate admissions. According to Keivan Stassun, a physics professor at Vanderbilt University who has written extensively on equitable access to graduate education, “Doctoral programs have put and continue to put outsize influence on GRE scores. As soon as you realize that, all of these other patterns become understandable.”

GRE scores have been known for decades to correlate with race and gender. The Educational Testing Service, which administers the GRE and other standardized tests, has taken steps to reduce that bias; though the gap is shrinking, it remains at greater than 10% of the possible score. That can be a problem at the triage stage of admissions, when committees decide which applications to review in depth and which are unlikely to be successful.

“If you sort your applicants by their GRE scores … because of the massive disparities in GRE scores that correlate with race and gender, your diverse applicants are going to end up being sorted to the bottom of the spreadsheet,” Stassun said. Once those candidates are there, he added, even if diversity in admissions is a priority, the ranked list predisposes the committee to think of more diverse candidates as less qualified.

Qualitative research suggests that triage based on GRE score is common across scientific fields because the average committee must assess so many applications. But as research has begun to show that, while predictive of first-year grades, GRE scores are not correlated strongly with measures like publication rate and completion time in graduate school, an increasingly large movement, cheekily dubbed GRExit, is demanding that admissions committees drop their GRE requirement.

Another approach is to reduce the committee’s focus on GRE scores while still gleaning some information from the test. That’s the route Marenda Wilson–Pham took when she was assistant dean of diversity and alumni affairs at MD Anderson Cancer Center. In an article last year in the journal CBE-Life Sciences Education, Wilson-Pham and her team described an intervention to reduce the disproportionately high triage of applicants from underrepresented backgrounds. Once, a GRE score or GPA below a threshold got an application set aside right away, and only an intervention from interested faculty could rescue an applicant. In the redesigned admissions process, applications with weaker scores are reviewed by a second committee; if the reviewers think a student has potential, they forward the application to the main admission committee, which is blinded to applicants’ triage status.

The safest bet

According to Wilson–Pham, now an associate dean at Rush University in Chicago, when admissions committees meet to discuss applicants who have cleared the triage hurdle, subtle bias may creep into their assessment of qualitative factors.

“People fall into this lull,” Wilson–Pham said. “They like to see candidates who remind them of who they once were. … If I have to bet on which person is going to succeed, it’s this person that looks just like me — because I succeeded.”

This type of bias, known to social scientists as homophily, isn’t only about race, ethnicity and gender. It can apply to any feature that a student and an admissions committee member shares, such as where they went to college or whether the applicant’s recommendation letter comes from a professor whose reputation the admissions committee knows.

At MD Anderson, where she both earned her Ph.D. and got her start in academic administration, Wilson–Pham used the Socratic method when she sensed reviewers saw some applicants as safe bets and others as risky. “It’s almost like a research seminar,” she said. “The way I’d get people to reflect on their behavior was to ask a bunch of questions. ‘Tell me why you feel this way about this applicant. Well, then let’s go back to this applicant that we reviewed an hour ago and this is what was said.’ … My job was to make sure that, for every applicant, the criteria were equal.”

Aware that a program’s future funding depends on student success, a committee with doubts about an applicant’s ability to succeed may hedge its bets by suggesting that student consider a master’s degree in the same department, generally with funding. Both Wilson–Pham and LaRuth McAfee, the senior assistant dean at the University of Delaware’s graduate college, mentioned this when discussing the preponderance of master’s degrees among black Ph.D. recipients.

“Maybe the student knows they want a Ph.D., but the program wants them to prove themselves,” McAfee said. “If they do well in the master’s program, they can stick around for the Ph.D.”

Anecdotally, both deans said that these offers are more commonly extended to students from minority-serving institutions. “It’s not that they’re saying, ‘We don’t think someone from this institution can cut it,’” McAfee said. “It’s more like, ‘We’re concerned that we’re putting ourselves at risk — and even concerned that we might be hurting the student by admitting them to a program in which, if they’re not successful, they’ll have fewer options when they leave than when they came in.’”

Some students seize the opportunity to attend their school of interest on any terms. Others recoil. When Zerick Dunbar was finishing his master’s degree and applying for Ph.D. programs, he received one counteroffer of acceptance into a master’s program instead. “I was like, ‘Uh, I already have a master’s?’ Getting another would be a waste of my time.”

I'm about to graduate. What are my options?

If you're interested in pursuing a Ph.D., there are many ways to get there.

Read more

Recruitment and retention

The National Science Foundation’s Graduate Student Survey indicates that, across the many disciplines of biology and biomedicine, about three people are pursuing doctoral degrees for every two pursuing master’s degrees. This ratio is about the same for white students. But it’s inverted for black students; there are three black Ph.D. students for every four black master’s students. Advancing further through academic career stages, the underrepresentation of black scientists becomes more and more pronounced.

“Students are making — I think in some cases justifiable — choices to do other things,” August said. “At the same time, I think we’re losing an opportunity to diversify faculty, because of the culture we have in the academy.”

Suzanne Barbour is the dean of the graduate school at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a longtime member of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology’s Minority Affairs Committee. She put the master’s-before-Ph.D. phenomenon in the wider context of academia’s inhospitability to underrepresented scientists.

“Any time there’s a stopping point in the pipeline, there’s a potential that you get lost,” she said. “Students may get the master’s and be satisfied with it. Or, due to the things that happened to them during the master’s, (they may) say, ‘The last thing in the world I want to do is go for a Ph.D.! I haven’t been treated well in academia.’

“A lot of things have been done in the last two generations. There are all kinds of pipeline-building programs, (but) everything tends to focus on recruitment, recruitment, recruitment.”

In Barbour’s opinion, it is time for the focus to shift to retention of underrepresented students and to increasing diversity and inclusion in more senior roles.

Outlook

“People in science are still people in science,” Gibbs said. “Even though our ideals are universal, science happens in a social environment. The biases that exist in the world shape how we do science and the experience that people from different backgrounds have in science.”

Many scholars have worked for years to unravel the way that those biases directly and indirectly steer young black scientists toward extra years of schooling or away from science altogether. For some of them, such as Michelle Jones–London, chief of the workforce diversity office at NINDS, students’ research experience prior to graduate school is coming into focus as a research topic of its own.

“We recognize that this needs more of a careful look,” Jones–London said. “We’ve seen what we think could be a potential difference (between well-represented and underrepresented graduate students) … the hard part is the ‘why.’”

Experts say determining and redressing the causes of underrepresentation are as much a strategic priority as an ethical imperative.

“There was a time when people thought of this as an issue of just plain diversity,” Barbour said. “But now, I think we have to start thinking about it in terms of the workforce and the leadership that the country needs to continue to be the global leader in research and development in the life sciences.”

(Two corrections were made to this article on Feb. 26, 2020: The name of Zerick Dunbar's college and information about Taylor Carmon's compensation were corrected.)

Historically black colleges and universities

The college experience can govern a student’s interest in, and preparedness for, further education. A disproportionate number of black Ph.D. students attended a historically black college or university as undergraduates.

“Those are institutions that have really mastered what it means to have cultures of inclusion and to provide support structures that ensure students come out armed to succeed in whatever they do,” Keivan Stassun, a physics professor at Vanderbilt University, said about HBCUs. “Many of our R1 institutions who have been working harder to increase the diversity of their student bodies still have a lot to learn from minority-serving institutions.”

For Briana Whitehead, a first-year biophysics Ph.D. student at Johns Hopkins who earned a master’s through a bridge program at Fisk University in Tennessee, the difference between her undergrad and her master’s program was stark. When she was an undergraduate, she said, “it wasn’t a community that I felt could foster my growth in being a scientist and continuing to be myself. When I went to Fisk, I was at an HBCU and I was able to be in a community where it was OK to be a black young woman in STEM.”

The time she spent in the program boosted her confidence in her ability as a scientist and also her ability to compete in the admissions process. When she chose a doctoral program, she selected universities with equally strong underrepresented communities.

Students from prominent HBCUs are courted by many graduate programs. However, some faculty at research universities lack knowledge of these institutions. When Kenneth Gibbs, a program officer at the National Institute for General Medical Sciences, was a graduate student at Stanford, he served on an admissions committee; one applicant was a senior at Morehouse College, and some faculty “hadn’t heard of Morehouse and didn’t know how to assess (the student’s) potential contributions or his ability to excel in the program.”

Gibbs said his answer was, “Well, have you heard of Martin Luther King Jr.? Because that’s where he went to school.”

BackBridge to doctorate programs

According to Keivan Stassun, a physics professor at Vanderbilt University, “Students have been figuring out on their own that where they initially can’t get access to a Ph.D. program, a master’s program can be a stepping stone.”

Launched in 1992, the Bridges to the Doctorate funding mechanism at the National Institutes of Health is designed to offer that stepping stone but with funding to reduce the financial burden on students. It pairs minority-serving institutions that offer a terminal master’s degree with predominantly white institutions that offer doctoral programs. When a student successfully completes the master’s, they receive admission to the Ph.D. program.

Stassun launched Vanderbilt’s Master’s to Ph.D. Bridge program in collaboration with Fisk University in Nashville in 2003. (The program is independent of the NIH program.) “Almost without exception, these are students who have applied to doctoral programs and been denied admission to every one of them,” he said. The program “provides a way for these students to demonstrate on site what their capabilities are.”

Avery August, who ran a Bridges to the Doctorate program as a professor at Penn State in partnership with Alcorn State in Mississippi, saw some applications to the bridges program from undergraduates who were already well prepared to enter a Ph.D. program. He said, “We specifically counseled those students to apply directly to Ph.D. programs.”

Sometimes, he added, those students were disappointed not to be accepted into the supportive community of the bridges program, so the program staff took steps to expand the extra mentoring and other activities to underrepresented students who didn’t need the transitional master’s step.

When a panel met to review the NIH funding mechanism in 2018, they concluded that it was unevenly successful: Some universities’ programs were very effective, while others had limited success in funneling underrepresented students into Ph.D.s and later faculty positions. The committee added that a lack of longitudinal data on student outcomes made it difficult to assess accurately.

BackI’m about to graduate and am interested in a research career. What are my options?

Ph.D. programs in biology and biochemistry are almost all funded. MS degrees are more of a mixed bag. If you want to earn a master’s degree, it’s worth looking for a program that will not charge tuition.

If you’re a year or two away from graduating, consider seeking out paid summer research opportunities; you can find a list on the ASBMB job board. (In the meantime, a Marion Sewer scholarship provides up to $2,000 to support tuition for undergraduates who enhance diversity.)

If the cost of applying to graduate school is a concern, you can apply for waivers of GRE fees and, frequently, application fees at individual schools. Many postbaccalaureate programs and some societies like the Society for the Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science will cover the cost of GRE testing for their student members.

Some students spend time between college and graduate school working as technicians at research labs. If you want more time in a structured program to think over whether a Ph.D. is the right choice for you, then consider programs that offer a stipend. The NIH sponsors a Postbaccalaureate Research Education Program with locations across the country as well as funded master’s degrees aimed at underrepresented students through the Bridges to the Doctorate programs (you can find a list by state here).

Visit the ASBMB Minority Affairs Committee’s webpage for more resources for minorities in science.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Upcoming opportunities

ASBMB's PROLAB award helps graduate students and postdoctoral fellows spend up to six months in U.S. or Canadian labs.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Upcoming opportunities

No matter where you are in your career and what future path you aspire to, everyone needs leadership skills. Join ASBMB for practical strategies for building and practicing leadership skills.