US travel bans: Bizarre and ruthless

In March 2020, just a week after my arrival in the U.S. to start a postdoc position at my dream lab in Cambridge, Massachusetts, then-President Donald Trump temporarily banned noncitizens who had been physically present in the U.K. and the parts of the E.U. known as the Schengen area in the previous two weeks from entering the U.S. I perceived this ban as an inconvenient yet cautious act aimed at containing a public health emergency. At the time, SARS-CoV-2 was not well understood or controlled in several European countries, including Spain and my home country of Italy.

Almost 17 months later, the presidential proclamation(s) remain in effect and even have been expanded. They now include the 26 Schengen countries, the U.K., the Republic of Ireland, South Africa, Brazil, India, China and Iran. If I were to travel to any of these countries from the U.S., I would be unable to return. I have not seen my family in a year and a half.

When Joe Biden was elected president, my hopes for a visit home skyrocketed. After all, his agenda included strong international cooperation, welcoming policies and science-based decision making. Surely, the days of travel bans on Europe and European scientists were numbered.

I was therefore disconcerted that one of Biden’s first executive actions was to reintroduce, on Jan. 27, the travel bans Trump had set to expire two days before.

“OK,” I thought, “nothing to worry about. January is still early. Cases are still rising, and vaccines are on their way but not quite there yet. Just hold on, and you will soon be able to see your family.”

Time passed. Vaccinations gained momentum both in the U.S. and in Europe, leading Biden to declare in April that the U.S. would lift the U.K./E.U. travel ban by mid-May. I could not contain my excitement. I finally would be able to travel home.

Come May, however, there was no news about lifting restrictions on international travels. June, no news. July, no news. No presidential declaration, no information on consulates’ or embassies’ websites. Nothing concrete in terms of policy changes. Nothing other than speculation in a few newspaper articles.

Hope was turning into frustration.

Eventually, pressure started to build: Journalists asked questions, airline and tourism companies lobbied the government, European diplomats got bothered about the lack of reciprocal immigration policies, and eventually the government was forced to provide some answers.

According to an April 30 presidential proclamation, “The national emergency caused by the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States continues to pose a grave threat to our health and security. … It is the policy of my Administration to implement science-based public health measures, across all areas of the Federal Government, to prevent further spread of the disease.”

This was the justification to keep travel bans. Thereafter, government officials repeated the phrases “science-based,” “data-driven” and “evidence-based decision making” as if they were a mantra. Biden recently reiterated his intention to keep travel restrictions in place.

Remarkably, this science-based approach only applies to certain categories of visa.

For example, M-1 and F-1 visa holders (largely students), green card holders and U.S. citizens are exempt from the restrictions. We still have much to learn about COVID-19; however, virologists would agree that susceptibility to infection does not change according to the visa type you hold.

To circumvent the restrictions, a traveler must obtain a so-called National Interest Exception, or NIE, from a U.S. embassy or consular post after they are already abroad. The NIE is granted only to a few categories of loosely defined essential workers. Consular posts can take up to 90 business days to reply to an applicant’s request, and approval is highly uncertain — the outcome depends on the consulate’s arbitrary discretion.

Some visa types are subject to further complicating restrictions; for example, under standard conditions, J-1 visa holders (mostly academics) are not allowed to leave U.S. soil for more than 30 consecutive days. The long time required to process NIE applications, combined with the fact that a request cannot be submitted until the applicant is outside the U.S., makes it impossible to apply without endangering one’s work and related immigrant status. The 90 days required to process NIE applications become even more grotesque if one considers that an average postdoc has between 15 and 20 days of vacation per year.

Aware of the absurdity of the situation, U.S. consulates and university international offices recently started to suggest NIE applicants take what is now known as “the third-country approach,” spending two weeks in a country not affected by the ban before reentering the U.S. These countries include Turkey, Mexico and Russia, places where the pandemic is still raging and vaccination programs lag behind those in Europe.

Such an approach is not based on science.

Forcing European researchers to travel to a third country exposes us to heightened safety concerns and financial burdens. Ultimately, it likely increases the spread of COVID-19 by forcing people to move through infection hubs such as airports, hotels and restaurants in several countries with high infection rates.

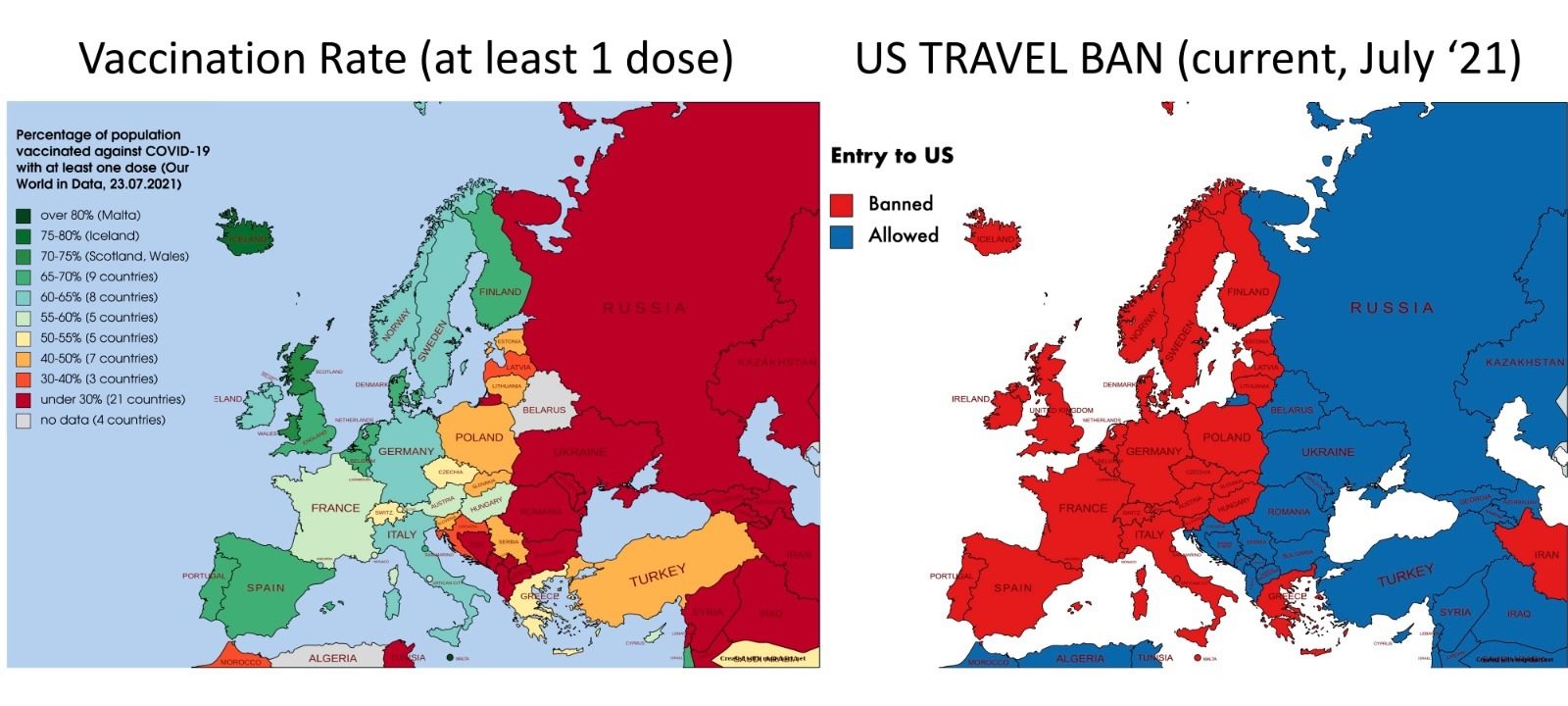

I would expect a science-based approach to protecting public health to allow travel from countries that have higher vaccination rates and lower infection rates while banning travel from countries where rates are worse. As of late July, however, this was not the case. In banned countries such as the U.K., Italy, Spain and Germany, more than 60% of the population had received at least one dose of vaccine, compared to 46% in Turkey, 30% in Mexico and 23% in Russia (and 55% in the U.S.).

When it comes to daily infection rates, the situation is no different. Mexico, the country with the fewest new daily cases among the three cited above, has twice the infection rate of Italy, six times the infection rate of Germany — and a 20% lower rate than the U.S.

These numbers are hardly reconcilable with a data-driven approach to travel bans.

Keeping the new delta variant at bay is also not a viable justification for the ban; according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the delta variant now accounts for 83% of new Covid-19 infections in the U.S. Considering the high efficacy of vaccines against symptomatic infections by delta, unvaccinated Americans are likely to pose a greater threat to public health than vaccinated Europeans traveling internationally.

The situation is bad, and the end is not in sight.

Even if President Biden revoked all travel restrictions tomorrow, a shortage of personnel and funds combined with the blockade of visa issuances to people who do not qualify for an NIE (but who otherwise legally would qualify for a visa) has created backlogs at U.S. consulates and embassies in banned countries that will take months to dissolve. This extends delays for people who need to receive or renew their visas. In June, the next available appointments for visa renewal at the U.S. embassy in Paris were almost a year away. This de facto visa ban now faces a legal challenge.

My American colleagues now can take a selfie in front of the Basilica di Maria Maggiore in Rome, enjoy an aperitivo in Florence or marvel at the Sicilian coastline. Tourists from many countries can visit New York or Yellowstone National Park while I, and millions of other international visa holders, have been kept from visiting our families for almost a year and a half.

A lot happens in a year and a half. Among cases that made it to the news is that of the Bloomberg anchor Jonathan Ferro, who had to watch his father’s funeral on his iPhone. But this is just the tip of the iceberg. The Instagram page Bring US Home is gathering stories of people affected by the travel bans, and some of them are distressingly sad. Couples have been separated since March 2020. Grandparents are unable to meet their newborn grandchildren. Adult children can’t help their ailing parents.

I was absent when my father had a tumor removed and my grandfather faced a life-threatening COVID-19 infection. I missed my brothers’ birthdays when they turned 11 and 15, and then 12 and 16. I couldn’t attend my own Ph.D. graduation ceremony. Fortunately, none of my stories ended tragically, but not everyone has been so lucky.

Such stories are not uncommon. Most international scholars have not been able to visit families or significant others for more than a year, with an indefinite wait ahead. This is affecting our mental health; many of us must choose between being present for the births, weddings and funerals of friends and family and the security of a job and immigration status in the country where we have established our lives.

A letter about the travel ban signed by more than a thousand scientists was submitted recently to the editorial board of the journal Nature. We hope it will help our voices be heard.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.