Transcript: Caring for caregivers and parents in STEM fields

The LinkedIn chat transcribed below discussed the barriers, support and resources encountered while managing the dually time-consuming roles of taking care of family and excelling in science. Panelists discussed their experiences and shared insights to help others who are or will be parents or caregivers in STEM.

The panelists were:

- Carlos Castañeda, ASBMB Maximizing Access Committee.

- Donald (Don) Elmore, ASBMB Women in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Committee.

- Frankie Heyward, National Black Postdoctoral Association.

- Martta Liukkonen, Mothers in Science.

- Ahana Maitra, Mothers in Science.

- Monica Malta, 500 Women Scientists.

- Raechel McKinley, ASBMB.

- Toni Mosley, 500 Women Scientists.

- Chelsea Rand–Fleming, ASBMB Advocacy Training Program delegate.

- Jessica Thomas, National Black Postdoctoral Association.

The conversation took place on the ASBMB LinkedIn page using the hashtag #Care4STEMCaregivers. This transcript was edited for length, clarity and style.

What is the best advice you received about balancing your career as a scientist and being a caregiver/parent?

Carlos Castaneda: “Balancing” is probably not the word I would use. The best advice I’ve had is to “be OK with the crazy and unexpected, and get sleep when you can.”

Honestly, I’m very grateful to my two departments for being very supportive of faculty with children. Many of the assistant professor cohort when I joined had one or two little children, so talking to all really helped me.

I’ve learned how to compartmentalize time to try and be more efficient, but I still really struggle with this. The other useful piece of advice I’ve been given is to accept that things (research, etc.) will slow down. I still try to heed my mom’s advice in staying in the moment. (I’ve struggled with that since I was little.)

- ↪ Toni Mosley: I love “be OK with the crazy.” That sums up most of my days, haha.

- ↪ Carlos Castaneda: Certainly helps me de-stress, Toni!!! And, truthfully, sums most of my days. :)

- ↪ Carlos Castaneda: One big reason why I’m happy to be in academia is the true flexibility of this job in handling the crazy; I can leave at a moment’s notice to pick up our child from day care if they are sick.

Jessica Thomas: The best advice was to seek out a life coach. The coach helps to balance work and home life.

Raechel McKinley: The best advice that I’ve received was to always make time for yourself outside of your work and caregiving. Even if it’s something small like taking a walk, watching a favorite TV show or reading a book. It’s important to schedule time for yourself.

- ↪ Toni Mosley: Yes! Self-care is a priority. I go out for karaoke with my girls every Thursday. It’s my treat-myself time.

- ↪ Raechel McKinley: Yes! You have to treat yourself!

Martta Liukkonen: I did not receive any advice when I first started my path in STEMM. I started my Bachelor of Science in biology program when my kid was 10 months old, and there was zero support. The majority of students don’t have kids over here, and every activity, group and club was not accessible for me.

Five years later, at the end of my master’s, I found Mothers in Science, and it was the first time I found a community that offered support and advice for parents and especially mothers in STEMM.

Now, in the middle of my Ph.D., I talk about my situation very openly and publicly and make sure everyone is aware that there is a huge lack of support for students and researchers that are not the (childless) norm.

Toni Mosley: Black women are expected to do it all not only by society but by ourselves as well. When I found myself struggling to juggle my responsibilities as the fellowship manager while taking care of my daughter full time, I realized I couldn’t meet my own expectations.

I didn’t know how to ask for help, because I was afraid of looking weak, which caused my work and my mental health to suffer.

When I finally reached out for support, I received a very simple piece of advice: “Never lose sight of your goals, but be realistic and forgiving.”

I’ve had to adjust some of my goals and push back some timelines, but now that I approach my work with that statement in mind, I’ve slowly started to relax and enjoy being both a mom and a STEM professional.

- ↪ Chelsea Rand–Fleming: I loooove this! “Be realistic and forgiving.” As Black women we are so very hard on ourselves! We can be our own worst critics sometimes. We need to realize we are human and deserve way more grace than we give ourselves.

- ↪ Toni Mosley: Yes, sis! I wrestle with it every day.

- ↪ Monica Malta: Yes!! The levels of discrimination experienced by Black women in STEM, and Black women with children in STEM is ... another level! Intersectionality matters, and institutions need to be held accountable. They need to offer better support. A DEI workshop every now and then changes nothing.

- ↪ Toni Mosley: Yes, girl! You said it! I can’t tell you how frustrating it was dealing with racism from co-workers, and the only discipline given was watching DEI videos. That’s when I realized I needed to advocate for others like me, and that led me to 500 Women Scientists.

Donald Elmore: All jobs have some constraints and some flexibility. I received advice to figure out the flexibility that my job offered such that I could best leverage it to do what I wanted in my personal life.

It’s also important to recognize that flexibility might change over time. I use flexibility very differently now with kids in middle and high school than I did when they were younger.

Part of this was also recognizing that in many (most? all?) scientific careers there is always another experiment one could do, another paper one could write, another … so just set the limit of what you are comfortable with doing for work and feel good about that. Much easier said than done, of course!

- ↪ Monica Malta: I couldn’t agree more! To find this sweet spot, our comfort zone — that’s key. ... And yes, it changes over time a lot!

Monica Malta: I guess we’ve all faced this key scientist’s dilemma: Can we be a parent, a caregiver, a partner, a friend AND a scientist? Life outside of academia, outside of the lab, is necessary. It is good. Our mental health needs it. And, surprise, we are more productive after some time decompressing and having fun.

Of course it is NOT easy to be a mother and continue working in STEM. And some work environments are just too toxic. I won’t lie: It is hard. But THE best advice I received came from a male colleague, a Ph.D. student (like me) who once told me, when I was pregnant: “Do you know that almost 50% of new mothers leave full-time STEM employment after having their first child?” Those remarks made me cry. I felt angry and lost. But it also pushed me to find a supportive environment. I switched to another organization and found a place that was welcoming for me as a scientist and a solo mother.

- ↪ Toni Mosley: I left the zoo field when I was three months. If I had been in a less toxic environment, I would have stayed. The zoo field is unfortunately extremely toxic and not very BIPOC friendly. It was one of the hardest decisions I’ve ever made.

- ↪ Monica Malta: Yes!!! As a Latinx in STEM, I completely agree with you. We already deal with lots of toxic places; we deserve a supportive work environment. Like our amazing friends at 500 Women Scientists.

- ↪ Toni Mosley: Yes. I can’t tell you how refreshing it is to be able to consider those women my tribe.

- ↪ Monica Malta: Yes!!! As a Latinx in STEM, I completely agree with you. We already deal with lots of toxic places; we deserve a supportive work environment. Like our amazing friends at 500 Women Scientists.

Ahana Maitra: To be very honest 😒, I haven’t received any support. I struggled a lot with my toddler and my Ph.D., and apart from some really helpful friends and a supportive partner, I have not found any support or advice from anyone that would have helped me professionally in STEMM. Most of my colleagues didn’t have kids.

I found @MothersinScience after I finished my Ph.D. And then I came across these amazing mothers who had faced similar situations, and now I also see more content over media and social media with lots of important tips for caregivers in STEM.

- ↪ Monica Malta: Friends were my No. 1 source of support, for sure! They still are.

- ↪ Ahana Maitra: Yeah, thanks to them, I am still surviving in STEM.

- ↪ Donald Elmore: I am sorry to hear that you haven’t found support within your institution and workplace, although I know that is all too common. I’m sure we will touch on how to build those institutional supports more in the chat, but I am glad that you’ve been able to start finding some support in other places. Will love hearing about those resources from others.

- ↪ Ahana Maitra: Thanks. I really wish that I would have found Mothers in Science when I was a Ph.D. student. It would have helped me a lot!

Chelsea Rand–Fleming: Give yourself props!! A lot of times we get so caught up in handling it all that we can get burnt out and not even realize how amazing we’re doing. Take time for yourself. Even if it’s just an hour of writing in a journal, taking a nap, eating lunch by yourself, getting a massage. Reward yourselves because you deserve it.

- ↪ Monica Malta: Yes, yes, yes!!! Self-care is sooo important, but we neglect it a lot. ...

- ↪ Chelsea Rand–Fleming: Yes!! We forget to take care of ourselves!

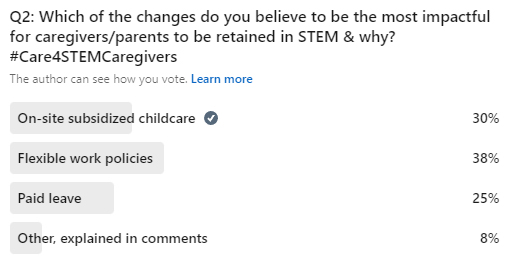

Please see the poll below.

Vimal Selvaraj: Why do we need to choose? Aren’t all these points relevant if there is an intention of providing support?

I would also say that support needs to be customized. Professional shortcomings can be unforgiving. In academe, scientists put in long work weeks to remain competitive. So provisions are needed not just to be able to function but to thrive — if the goal is to ensure success.

Jessica Thomas: There need to be funds or staff available to help. Some people are the sole parent or caregiver. Being able to afford care frees up time for the parent or caregiver to meet milestones.

Raechel McKinley: Federal and state legislation to respond to the high cost of care for the elderly. Assisted living, nursing homes and at-home care are so expensive, and most retirees cannot afford to pay for care on their own. In addition, the cost does not include medications, doctor visits or personal care items. Unless your loved one is a veteran or made wages below the poverty level during their career, they do not qualify for most subsidies, so family members have to contribute to paying for the cost of care, which is thousands per month.

Legislation to expand subsidies to working-class retirees will help offset the cost (which is increasing each year with inflation) and allow for families to breathe.

Although I’m not a parent, I know that day care and preschool is also costly, with many spending thousands a month on child care. Expanding the child care credit or creating more subsidies for parents at the federal and state level need to happen as well.

Chelsea Rand–Fleming: This one was very hard to choose from, but for me I believe having more flexible work policies would be amazing. I think this could also depend on the age of your child, but as a mother of an elementary aged child, my daughter gets sick ALLLLLLL the time. So many viruses going around, and there have been seemingly countless times when my husband and I have had to decide who was going to miss work to stay home with her when she’s been sick.

Another issue is having to choose between work and attending parent luncheons at school, holiday musicals, field day, going on field trips as a chaperone. I don’t want to have to choose between being considered a good worker and being a good mom. I’d love the option to work from home or even to work different days/hours than normal to ensure that I can attend my child’s functions.

- ↪ Donald Elmore: And going to those events is such fun! (Well, most of them. … After riding a bus full of screaming fifth-graders to a field trip once, I decided that was something I could schedule meetings over in the future!)

Carlos Castaneda: For us, it would have been far more helpful to have on-site subsidized child care. It’s rare to see a university setting with available child care that doesn’t have a multiyear waitlist. One thing I am appreciative of from our university (Syracuse University) is that they do offer a child care subsidy for faculty/staff, and we have been able to use these funds to offset day care costs and after-school activities for our children. But in general, this type of subsidy needs to go to all levels (graduate students, etc.).

- ↪ Donald Elmore: Just wanted to emphasize the part on benefits being available for people throughout their trajectory (including as graduate students). Even with having very supportive graduate advisors, I just don’t know how we could have balanced the initial parenthood piece at that point. Thinking about child care, leaves, etc. for that stage is critical for the STEM pipeline.

Donald Elmore: I’ve had a few conversations with colleagues about the child care option and would love to hear from others in this chat.

*Subsidizing* child care — which is notoriously expensive — can be a great policy. But I am more ambivalent about it being on site, as that can lock families in.

In particular, if there is more than one parent, that ultimately means that the parent with workplace care ends up with many more of the day care/preschool related duties (including being the main contact whenever a child inevitably gets sick during the day).

Personally, we found it much easier to have our children near our home versus either of our workplaces so either of us could drop off or pick up the kids if one of us had a late meeting, was out of town for work, etc. But I know this differs by individual circumstances.

- ↪ Ahana Maitra: We have always struggled with this decision. Near our home versus workplace.

- ↪ Martta Liukkonen: Good points!

- ↪ Toni Mosley: I think it goes back to balance. I agree day care responsibilities would become a little one-sided, but that means the partner should pick up the slack at home. Sometimes parenting is a tag team wrestling match.

- ↪ Ahana Maitra: Sometimes? For us, it´s definitely ALWAYS!!!

- ↪ Toni Mosley: Girl, me too, haha. I tag out right when my husband walks through the door. 😆

- ↪ Ahana Maitra: Sometimes? For us, it´s definitely ALWAYS!!!

- ↪ Toni Mosley: I think it goes back to balance. I agree day care responsibilities would become a little one-sided, but that means the partner should pick up the slack at home. Sometimes parenting is a tag team wrestling match.

Ahana Maitra: For me, flexible work policies would be the topmost priority. I have always worked in molecular labs, so I know that there are days when you can’t work remotely, but there are other days when you can be flexible, and you should get this option of nonconsecutive work hours or remote work. The pandemic has taught us that remote work works, and being in STEM doesn’t demand a strict 9-to-5 work culture; you can be flexible and equally productive.

But on-site child care and equitable paid parental leave are also very much important for parents in STEMM. In fact, all three of them are required to retain caregivers/parents in STEMM. All of these should have been here already. It is unfortunate that we have to think and try to choose the most impactful one! :-)

Martta Liukkonen: I would say all three are needed!

1) On-site child care removes a lot of stress from the primary caregiver’s shoulders, which is then linked to work efficiency. Child care costs in many countries are extremely high and not realistic for academics. Not being able to afford child care will directly result in primary caregivers needing to reduce their working hours and devote less time to their research, teaching, etc.

2) Flexible and remote work policies enable parents to organize their work schedule around school pickups, PTA meetings, etc. Personally, my work doesn’t require the basic 9-to-5 but is more about time management and getting things done efficiently, whether at the lab or at home. I would add here that flexibility and support are needed also in fieldwork, as many parents, especially solo parents, are not as able to take part in fieldwork because of child care duties.

3) Equitable paid parental leave is a must! For starters, taking care of a baby is a full-time job with very little sleep, not to mention when the kid grows older. If there are two parents in the family, then both should have equal amounts of paid leave.

Donald Elmore: I find the need for *equitable* leave to be particularly critical. I truly appreciate at my institution that all faculty receive a full paid one-semester leave after the birth or adoption of a child.

Critically, I had senior (male and female) colleagues who talked about their own leaves — and emphasized how this was truly a *leave* to step away from work. That made me feel confident to do the same after both of my own children were born.

I also think that this sent an important message to our undergraduate students (Wellesley is a primarily undergraduate institution) who saw their faculty mentors (of all gender identities) placing a priority on their family responsibilities.

- ↪ Toni Mosley: It’s so important that men are included in these conversations. My husband only had two days off and had to go back to work the day after we went home. Luckily, my parents came cross country to help for a month, but it really affected my husband emotionally.

- ↪ Donald Elmore: Absolutely — I can’t imagine having to go back so quickly! I look back so fondly on those days at home with both kids (makes me likely to start digging out some old photos!).

- ↪ Toni Mosley: Haha, I’m so happy you got to share in that experience.

- ↪ Donald Elmore: Absolutely — I can’t imagine having to go back so quickly! I look back so fondly on those days at home with both kids (makes me likely to start digging out some old photos!).

Isabel Torres: All of the above!

Monica Malta: I think COVID-19 showed us that remote work and flexible working arrangements are key. Post-pandemic, I hope this flexibility will be the norm for folks working in STEM — that allows parents to take turns when a child is sick, when there is a school meeting, etc. The productivity penalty paid by mothers, or motherhood penalty, in STEM is pervasive across many industries and workplaces. Targeted policies like improved child care or more flexible hours are important but not enough. Leaders also need to proactively challenge the narrative that motherhood can’t coexist with success in an elite STEM career.

Toni Mosley: This is hard, because all of these options would be extremely impactful, but child care/day care is astronomically expensive. It’s a blessing that I am able to stay home with my child, but for those who do not have that privilege, paying private school–level tuition for your baby or toddler is really daunting and can be financially crippling. Not only that, but providing on-site child care gives caregivers/parents peace of mind over their child’s safety and cuts down on mental, emotional and physical fatigue.

↪ Carlos Castaneda: Your points, Toni Mosley, are very well taken; all of these factors (cost, especially) were in the back of our minds when we were deciding WHERE (city, university) would be a good place to work and raise children.

There have been calls for a cultural shift in STEM and academic research to accommodate and respect individuals who take on caregiving responsibilities. What do you think are the first steps to achieving this?

Prathipati Vijaya Kumar: Need of the hour.

Frankie Heyward: I think bringing awareness to this issue is key so not only STEM parents but also their employers, administrators, institutional leaders, policy makers and government officials know how difficult it can be to make ends meet in life and in the lab without needed child care reform. After public awareness campaigns have stimulated a needed discussion, then I think institutions will be persuaded to enact policies that will offset the burden, such as greatly subsidized child care and substantially expanded parental leave. I would hope that those in positions of power, when made aware of the unbearable child care climate, would be morally convinced to do something about it.

Raechel McKinley: I think you have to make STEM and academia more inclusive, and to do that, you need to create a different environment that is centered on personal well-being. I think a lot of times science gets the priority, and the people driving the science and innovation get pushed back.

Isabel Torres: Research shows that policy drives societal and cultural change. Maternity bias is widespread in STEMM, and our leaders need to have the courage to acknowledge the problem and start implementing policies to remove the barriers faced by parents and caregivers, and especially mothers, as they are disproportionately affected (and especially mothers from marginalized communities). Here is a short video we made to raise awareness of the maternal wall in STEMM: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZiYGVMCqQGI&t=2s .

Carlos Castaneda: Emphasizing the key point that caregiving is not a weakness in your scientific career. I think the first thing to do is to just ask people what they need. Everyone’s caregiving responsibilities differ. For instance, it’s hard for us to attend activities after 5 p.m. during the week. I’m not a huge fan of virtual meetings, but it has certainly happened that a few folks are unable to attend in-person meetings due to someone getting sick unexpectedly and having to stay home. I’m grateful that our departments have been responsive to these needs and provided options.

Martta Liukkonen: There are systemic barriers in the STEMM sector that won’t change without concrete policy actions. Primary caregiving and parenthood need to be made more visible and normalized. Instead of urging primary caregivers and parents to “adjust to the STEMM way of work,” workplaces should remove the barriers that lead to, e.g., the leaky pipeline.

Chelsea Rand–Fleming: The most important thing is realizing that caregiving is something that affects so many people that, statistically speaking, it doesn’t make professional sense to not address it.

More and more professionals are deciding that they do not want to work for an employer that does not seem to accommodate or respect employees that have outside obligations. Presenting statistics that clearly show how many workers this issue affects may appeal to the business side of things.

Certain companies may not ever care about people who are caregivers or parents, but they do care about the bottom line. If they realize that by implementing more caregiver-friendly policies they could retain more employees, I think this would be more readily achieved.

Donald Elmore: We’ve already touched on this in the discussion, but I think it’s critical to normalize taking on care responsibilities and not treat it as an exception. This is a case where I have felt very fortunate.

Accommodating child care or elder care conflicts has been considered normal in my department (and never needed to be defended) when giving teaching schedule constraints, scheduling committee meetings, etc. And it was also important that child care wasn’t the only personal conflict that would be considered so it didn’t single out (or prioritize) only some members of the department.

I also appreciated having senior colleagues who were open about their own challenges in balancing many aspects of their lives and (in my mind, very successful) careers. Now that I’m more senior (!?!), I have tried to integrate aspects of how I try to balance work and family (even as simple as just mentioning when I’m headed out early for a school event) in conversations around junior colleagues and students to continue that normalization.

Toni Mosley: Abolishing the idea that being a parent, especially a mother, is a weakness or career barrier. PAID (at least 80%) maternity/paternity leave. Not receiving maternity leave was disappointing, but my partner was able to pick up my slack. However, I know many people are struggling with medical bills, child care, etc. because they have no financial support whatsoever.

- ↪ Donald Elmore: Not only is it not a weakness or a career barrier, but I wish institutions could recognize that those experiences can make one *better* at one’s job!

Monica Malta: I think that STEM leaders and employers need to confront cultural beliefs that STEM professionals with caregiving responsibilities are less valuable, less committed to their professional work and less productive than their colleagues without these responsibilities. We need a cultural change, not just child care or flexible hours — but we NEED those as well. We really do!

One of the first steps, in my opinion, is to truly open the dialogue. Leaders, department chairs, deans gotta be humble and open to a hard dialogue; they gotta listen to parents working in STEM, especially those experiencing additional layers of discrimination such as Black solo moms and queer moms or those living with a disability (for instance).

Leaders need to brainstorm solutions that might work in a specific environment and not in others. Tailored strategies developed with and for affected communities are the key to start addressing this huge underrepresentation of women and queer people in STEM.

- ↪ Ahana Maitra: Couldn’t agree more!

- ↪ Donald Elmore: “Leaders need to brainstorm solutions that might work in a specific environment and not in others.” Couldn’t agree more. These solutions aren’t going to be one-size-fits-all but will require a shifting of perspective on what is valued.

- ↪ Toni Mosley: I agree, but along with breaking down those misconceptions, we need to leave room for emotional and physical healing AFTER returning to the lab/field/classroom and so on.

- ↪ Monica Malta: Oh yes. … Going back was hard!

Ahana Maitra: First, we need to start by increasing mothers’ visibility and raising awareness of the systemic barriers holding them back. Until recently, mothers in STEMM were invisible, and even nowadays, they remain isolated. This was our first aim at Mothers in Science — to connect mothers in STEMM, raise awareness of their challenges and break myths that mothers choose family over career when actually mothers are forced to make this “choice.”

Then we also need our leaders to take action and enact policies to create a system that is inclusive for everyone, including parents and caregivers. There is growing evidence, including our own research, showing that systemic barriers related to motherhood are driving the major leak in the STEMM pipeline, but this problem has been ignored forever.

Now that there is more awareness and data to show that the STEMM sector, and the workplace in general, is not designed for people with caregiving responsibilities, policymakers really need to begin taking action.

What were/are the main challenges that you struggled/struggle with as a parent and/or caregiver in STEM that have affected your career, and why?

Raechel McKinley: The main challenge that I faced was when I first became the primary caregiver for my father. I had to take months off — almost a year total — to care for him. I struggled with finding an assisted-living facility that was in our budget in the beginning, so I had to take care of everything, which limited time to focus on my courses and lab work.

Jessica Thomas: The main issue for me has been the affordability of child care — making too much to get assistance and not enough for it to not be an issue.

Donald Elmore: It’s so easy to say, “Good enough is good enough,” and I try to give that advice to those around me. But I don’t necessarily listen to it, whether in terms of work or home. At one point, we decided to come up with a family motto to embrace this: “We show up, mostly on time.” Seems true for me in about all dimensions nowadays, and I try not to feel the guilt about the extra I could have done and stay in the moment.

Chelsea Rand–Fleming: The main challenge for me as I am trying to obtain my Ph.D. was (sorta still is) work schedule. As a researcher on a teaching assistantship, there was a lot of mass confusion when I required teaching assignments that allow me to be able to drop off my daughter before work and pick her up after work. It was interesting because when I brought the issue up, it seemed like an issue that nobody was familiar with having to accommodate.

I couldn’t be demanding, but I had to be firm in my stance that I absolutely had to be able to guarantee that I could be in place for getting my daughter to and from school. After the buzz of confusion and chaos, we eventually found something that worked, and they just assigned classes to me that were midday and would not interfere with my mom schedule! I am glad I made my needs very clear so that the lines did not get blurred further down the line.

- ↪ Carlos Castaneda: Right! You just can’t be late for day care pickup! Routine really helps my kids too (set pickup and drop-off times). I also let my lab know that I just can’t be here after 5 no matter what (meetings have a hard stop). I totally hear you on this one, and it’s such an important conversation to have. I’m glad you were firm with your needs!

- ↪ Chelsea Rand–Fleming: Yes I have to be very firm. Even with our mandatory group meeting, my boss now knows that no matter how long the meeting lasts, I can only stay until 4:45, 5 at the very latest! He has been very understanding of that.

- ↪ Donald Elmore: I’m so impressed with how you navigated this. It can be a very tricky situation, particularly when you encounter supervisors who haven’t thought of it before.

- ↪ Chelsea Rand–Fleming: Thank you! It was very tricky and scary at first trying to figure it out. I didn’t want to feel like I was rocking the boat, but sometimes the boat has to be rocked.

- ↪ Toni Mosley: Self-advocacy is key! They really try to play the shame game.

- ↪ Chelsea Rand–Fleming: Yes, in a lot of cases if we don’t advocate for it ourselves, it won’t happen!

- ↪ Toni Mosley: Especially for Black women.

- ↪ Chelsea Rand–Fleming: Yes, in a lot of cases if we don’t advocate for it ourselves, it won’t happen!

Monica Malta: Lack of PAID maternity leave: That was the No. 1 struggle for me. As a solo mother, it was hard. I thought that I would never, ever go back to my field. But, against all odds, I’m still here. Three kiddos after. 😊

But talking specifically about mothers in STEM, we also face discrimination, drops in productivity, and inequities in wages and promotion — all of which contribute to this huge dropping of full-time STEM workforce. Birthing parents who take extended breaks from STEM careers face an uphill climb to resume them.

Toni Mosley: I left my career as a zookeeper soon after finding out I was pregnant, because my facility was extremely toxic, and I entered a new field with my current position. I was used to working outside every day and living a very active lifestyle while working with lions, jaguars and grizzly bears, and now I watch my daughter full time and work from home.

Don’t get me wrong, I love getting to be with my baby, but I’d be lying if I said I didn’t miss the excitement of working with dangerous carnivores.

It’s been really hard adjusting to the isolation of remote work, the fear of leaving my passion, starting something new, all while taking care of a newborn baby. It brought on a lot of anxiety, fatigue and guilt.

- ↪ Monica Malta: Oh dear! That breaks my heart. You’re not alone. I had to stay away from my field for two years but went back. Perhaps it won’t be in this specific institution, but I really hope you will go back to your passion!

- ↪ Toni Mosley: Thank you! I really love what I do now, but I’m hoping to go back as a DEI director or consultant. I'm looking at that new generation of BIPOC zookeepers.

- ↪ Donald Elmore: I initially wanted to make a joke that taking care of the carnivores might be safer in many ways than caring for a newborn. But I didn’t want to make light of this challenging cluster of experiences you are having. Newborn phase can be isolating no matter what, and I imagine that adding those other transitions and remote work just makes it that much worse.

- ↪ Toni Mosley: Haha, some days I’d rather shovel lion poop than change a dirty diaper. I appreciate the empathy though. It’s definitely hard, but with therapy and a great support system, I’m working through it for the better.

- ↪ Chelsea Rand–Fleming: You are not alone. There are definitely career sacrifices that I have had to make in order to provide my daughter and me the best environment to grow and thrive in! It can be so hard, but it’s worth it every time.

Carlos Castaneda: The main challenge with little children for me was sleep. I still remember bringing Luke (our oldest now) to work when he was 3 months old and realizing that he would only sleep on my shoulders while I kept moving (I got really good at squats back then). It is very hard to write grants being sleep-deprived. (Super grateful for paternity leave and tenure clock extension as a parent.)

Second-biggest challenge was/is feeling guilty every time I couldn’t help my wife with child care or feeling guilty that I let someone down at work because of child care responsibilities. Honestly, this last sentence is something I still struggle with. My wife and best friend is amazing, and I count my lucky stars every day.

Third-biggest challenge is missing out on connections/networking just because it’s hard to travel to meetings. But I will say — I’m grateful that we’re allowed to bring our kids to departmental events (even noon-time research seminars!).

- ↪ Toni Mosley: Wow. Your job sounds so accommodating! I love that for you!

- ↪ Carlos Castaneda: It was important to me to ask these questions when I was going through the faculty hiring process. I got advice from other STEM faculty/parents to ask about these policies, and I’m grateful to them for making me aware of how different university policies can be.

Martta Liukkonen: For me, the main challenges during my Ph.D. work have been being able to take part in work that requires travel (e.g., conferences) and fieldwork outside of school or day care hours and weekends.

I recently had to cancel a talk at a conference because they did not offer child care even though they asked about child care needs in the registration form. They claimed that they had no money for organizing on-site child care. I later found out from other participants that they did actually have the money but just did not think hiring a professional nanny for a few hours was important.

I miss out on a lot of networking events because I cannot get a nanny or the event does not offer child care.

Also, money is a big struggle, as my Ph.D. research grant is small compared to living costs in Finland, and because of this I am considering moving away from academia after getting my Ph.D.

- ↪ Monica Malta: Yes … and honestly? Most of my friends who left academia after their Ph.D.s are doing amazing and have more support at their workplace and less stress.

- ↪ Martta Liukkonen: I’ve heard very encouraging stories from former colleagues that work outside of academia now!

Ahana Maitra: The main challenge that I faced as a mother in STEMM was no longer being considered to take up more responsible roles. I was never encouraged to go to conferences or important meetings for future collaboration. I was never invited to participate in important research projects. Sometimes, I was even told that as I am a mother, I have to take care of my kid first, so I may not dedicate myself totally to work, etc. It definitely affected my chances to gain more visibility as a researcher, and I missed several chances for collaboration. I also struggled to prove my dedication.

I have to constantly prove that I can contribute equally to any other professional in STEM and being a mother does not make me less productive. It was exhausting.

- ↪ Monica Malta: I hear you. … It is exhausting! But you’re NOT alone. Keep connecting with all of us. Whenever we find grants or tips or something else, we are always sharing.

- ↪ Isabel Torres: I can totally relate to that, as can most mothers I’ve spoken with. You are not alone!

What policies or resources could research institutions have to better support parents and/or caregivers?

Raechel McKinley: Having support groups for caregivers would be good. It would have been nice to have a group to lean on and know you’re not alone. I don’t think there is a lot of discussion around caregiving for elderly parents, especially those who have a form of dementia. Having a place to go to share resources and helpful tips would’ve been great.

- ↪ Donald Elmore: I also wonder if some of the conversations we are having about subsidized (and close to work) care for children are also relevant in thinking about eldercare — which has many of the same challenges, but isn't necessarily time limited in the same way (our parents won’t “graduate” from day care/preschool).

- ↪ Raechel McKinley: Yes! However, there is the issue of not enough adult care services, or assisted-living facilities.

Frankie Heyward: Offer drastically subsidized, high capacity, on-site child care facilities. Many institutions offer subsidized child care, but the waiting list is often a year plus, and on top of that, the subsidy only defrays the costs by about 25%, which leaves a large amount to be paid by STEM parents living in regions where child care costs are excessive; infant child care can cost $3,000/month in Boston, which is still expensive despite most institutional subsidies.

- ↪ Monica Malta: That is INSANE! Boston is banned from my list. …

- ↪ Carlos Castaneda: That is insane indeed. I will continue to advocate for folks to move to other affordable cities that are lesser known but hold great promise.

- ↪ Frankie Heyward: It’s REALLY bad, but I’ve heard similar accounts from those on the West Coast, unfortunately.

Carlos Castaneda: I second Monica Malta’s point about all institutions needing to have paid parental leave and child care support. This should go for all graduate students, research technicians, postdocs, staff, faculty, etc.

Chelsea Rand–Fleming: Having either child care support or on-site child care would be phenomenal. Child care is so very expensive! At some point it feels that you are only working just so that you can afford your day care bill. It is a brutal cycle. Yet having child care support be automatic would be such a relief. Additionally, some researchers may have to choose between focusing solely on research or taking an extra job to be able to afford child care expenses. This without a doubt takes away from the time and dedication a parent or caregiver can dedicate to a research project. Another policy would just be the flex time. Allowing workers to be flexible with when and how they work as long as the research gets done.

Toni Mosley: Providing access to mental health resources and therapy and helping to offset the cost of those services as well.

- ↪ Ahana Maitra: Absolutely must!

- ↪ Toni Mosley: Postpartum is no joke!

- ↪ Ahana Maitra: Yes, totally get you!

- ↪ Toni Mosley: Postpartum is no joke!

Donald Elmore: I know that I’ve been focused on the parenting side of caregiving in my comments (it’s the life I’ve been leading!), and that is clearly pressing for many of us. But I’d also appreciate hearing thoughts on this (or other questions about cultural shifts or challenges) from those who have been balancing other caregiving situations (e.g., parents, partners, etc.). I will admit I don’t have as clear of a sense of whether there are other policy approaches to consider in those situations, although I know they impact many of my friends and colleagues.

- ↪ Raechel McKinley: Paid sick leave for those who have medical power of attorney of parents with dementia when they are hospitalized. When they’re sent to the hospital, it is the power of attorney’s responsibility to make sure they are there to answer questions from the physicians and be there to make decisions.

Martta Liukkonen: Subsidized child care and paid parental leave would be a great start! This would enable more mothers and other primary caregivers to focus on work instead of worrying about child care or not being able to afford one. Meetings that are held during standard office hours and the ability for paid sick leave and remote work options — e.g., when kids are sick, at home, etc. Also, grants targeted for mothers and other primary caregivers, grant extensions, and support for mental and physical well-being.

- ↪ Donald Elmore: “Also, grants targeted for mothers and other primary caregivers, grant extensions, and support for mental and physical well-being.” Related to this, has anyone in this conversation had experiences (or have thoughts from colleagues) with any reentry programs that target those who have stepped away from research/science for caregiving or other responsibilities (e.g., the NIH research supplements to promote reentry and reintegration)? Are there ways to improve those programs? Or ways for institutions to manage their own programs for that work?

Monica Malta: I would say: ALL institutions need to have paid parental leave and child care support for parents.

And parents in academia should not be seen as folks that don’t commit enough ’cause we are not working until 10 p.m., or we didn’t respond to an email sent on Sunday afternoon, or we cannot attend every single off-site conference. This insane workaholic environment is really toxic.

- ↪ Martta Liukkonen: Yes! The toxic work environment and the idea that true commitment is working at least 12 hours a day needs to be gone. It is ridiculous that many academics live by this workaholic rule even though there are numerous studies that show it is detrimental to our health and brain function (which I hope is still needed in research :D).

- ↪ Toni Mosley: Yes to all the above. As a parent, undying loyalty to your job is impossible and unreasonable.

Ahana Maitra: As we were discussing earlier, an on-site child care facility in research institutions would be a great support for parents and/or caregivers in STEMM. It will definitely take away a lot of stress and will also help a lot financially.

The institution can also provide a support group where parents/caregivers can voice their concerns, and the management can actually take some actions regarding these concerns. This will also create awareness in general, and the hardships faced by parents/caregivers in STEMM will be better acknowledged and hopefully resolved.

What are your favorite resources to share with scientists that are assuming caregiving responsibilities?

Raechel McKinley: For those who are caring for a parent with dementia, I recommend going to the Alzheimer’s Association caregiving website. There are a ton of resources, but finding the local support groups provides the most assistance; there you will find other caregivers who can help you find affordable care, whom you can vent to, and who can help you learn how to laugh during difficult times:

Ahana Maitra: Mothers in Science has been publishing useful resources for mothers/caregivers in STEMM. For example, we have a comprehensive COVID-19 hub with lots of information and resources about the impact of the pandemic on mothers in STEMM.

We also have a mentoring program for mothers in STEM, host many useful online events, and have published over 100 amazing journeys of mothers (and some fathers too!) in STEMM to create awareness of the barriers they face and how they handle them. Also, since the pandemic, there are more organizations creating awareness and discussing caregiving issues, just like we are doing here, and some have useful resources.

Monica Malta: I love the work that Isabel Torres makes at Mothers in Science. Please check it out: https://www.mothersinscience.com.

Martta Liukkonen: Mothers in Science has very good resources that can be used throughout the STEMM sector. And because many academics love to see the data, I talk (and rant) about the latest studies that show the inequalities that women and especially mothers in STEMM face in the STEMM sector.

Toni Mosley: I love sharing tips and resources on breastfeeding at work and on the go.

Breastfeeding parents have to be able to advocate for themselves, especially in male-dominated STEM fields. That’s why knowing your rights as a nursing parent at work is imperative. You can check out laws for nursing individuals in the workplace on the Department of Labor website.

Online support groups, as I mentioned before, are very helpful for tips and advice, and lastly, 500 Women Scientists’ SciMom program has lots of resources to help caregivers/parents in STEMM.

Monica Malta: We sure do. Please check out the 500 Women Scientists website for more info; our SciMom activities are here: https://500womenscientists.org/about-scimom-journeys.

In addition to the caregiving grant to attend #DiscoverBMB, what other things could the ASBMB be doing to support our members that are parents and caregivers?

Raechel McKinley: I would say having more events like this. I think it’s important to have these conversations and exchanges of resources.

Ahana Maitra: ASBMB could give awards to student parents who really struggle financially and often are not eligible for parental leave or child care subsidies. You could also give awards or grants to researchers who are solo mothers (or solo fathers if they are primary caregivers) and/or to mothers from marginalized communities who struggle with additional systemic barriers and layers of discrimination.

- ↪ Toni Mosley: THIS!

Chelsea Rand–Fleming: I think a possibility would be to offer the option of presenting virtually. For instance, you would present virtually to the people who are physically at a conference. That allows a scientist to present who can’t afford to bring their child or cannot afford to pay for child care while they are away. This gives an opportunity to still share your work with the same audience of people.

Another idea could be to have an option for other ASBMB members to donate toward caregivers as they register for the conference. That way there are extra funds to help out.

Toni Mosley: Adding to Martta Liukkonen and Donald Elmore, ASBMB can continue to host more events like this that amplify the realities of being a parent/caregiver in STEM and be a vocal leader on a global scale in the fight for pro-parent/caregiver work benefits, programs and policies.

Monica Malta: I’m not sure if your conferences have lactation rooms available for nursing mothers, but if you don’t, please do so. It is also important to make arrangements to have child care at the conference spot or nearby facility at subsidized prices for attendees.

Donald Elmore: Attending conferences can be a critical networking opportunity, but many colleagues with younger children feel these are too hard to coordinate. Although I know it could be logistically challenging, it would be helpful if ASBMB allowed those with caregiving responsibilities to provide preferences on when to have talks or posters scheduled when submitting abstracts. Often colleagues with young children might be able to have a partner, parent, friend, etc. cover care some days of a conference but not others, but if they aren’t certain of which day they would have to present, they don’t even submit the abstract.

Also, now that ASBMB committees can meet via Zoom, participating in them could provide networking options for those who may not be able to attend meetings as actively. So giving some priority for committee slots to those who aren’t able to attend meetings in person in the short or longer term for care responsibilities could help them stay actively engaged.

- ↪ Isabel Torres: Hybrid conferences with networking opportunities to attendees participating remotely. Still, child care support, in whichever form it’s provided, is fundamental.

Martta Liukkonen: ASBMB is doing a wonderful job with this caregiving grant and helping raise awareness of these issues with events such as this one. It is important to keep the conversation going and continue raising awareness with events like this and by hosting a session or workshop with expert speakers in their annual conference to discuss challenges of parenting and caregiving in STEMM.

They can also increase visibility of mother scientists, maybe by featuring their members who are parents or caregivers with interviews in their magazine/website.

Finally, the society can support organizations such as ours to increase visibility of the available resources and our initiatives to support parents and caregivers (example, mentoring program, community for solo moms) and to help advocate for change.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Upcoming opportunities

ASBMB's PROLAB award helps graduate students and postdoctoral fellows spend up to six months in U.S. or Canadian labs.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Upcoming opportunities

No matter where you are in your career and what future path you aspire to, everyone needs leadership skills. Join ASBMB for practical strategies for building and practicing leadership skills.