How the Julius lab found that an ion channel senses heat

The 2021 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine was awarded to David Julius and Ardem Patapoutian for their discoveries of receptors that sense temperature and pressure, work that exemplifies how difficult research can be. Through hundreds of mice, tens of thousands of cells and millions of bacterial colonies, the research groups that made the winning discoveries persisted in asking important questions about the molecules behind sensation. “The Secret History of Touch” tells five stories of their persistence. Here is the second.

The wiggle–waggle experiment

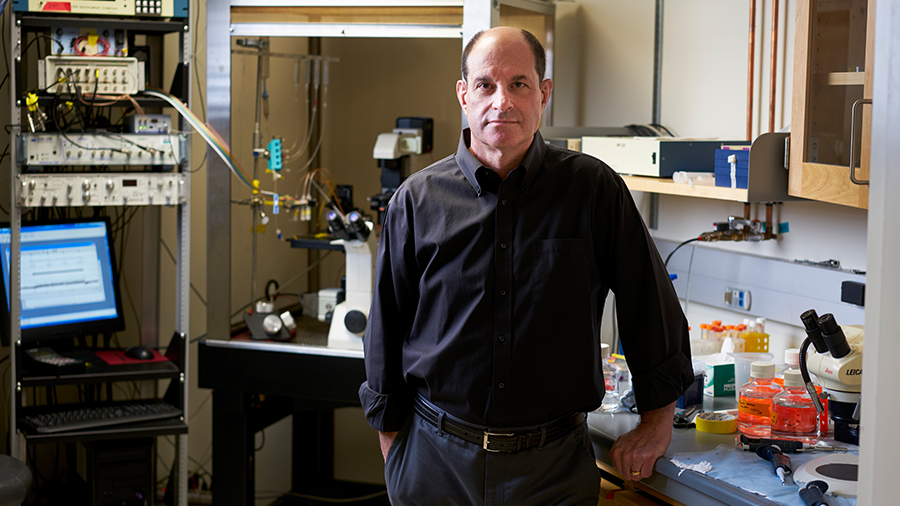

While trying to determine what makes hot peppers painful to touch, David Julius’ lab found the receptor that binds to capsaicin, an ion channel called TRPV1 that is expressed in pain-sensing neurons that innervate the skin. They doubted that was all TRPV1 did; capsaicin, they reasoned, most likely hijacked a pain-sensing system that mammals already had.

But for technical reasons, the assay Michael Caterina had used to identify the channel, which used calcium sensors to make capsaicin-responsive cells light up, was not well suited to finding other stimuli.

“That’s when this dual approach of using patch clamp electrophysiology and oocyte two-electrode voltage clamp (recording) became really helpful,” Caterina said. “Makoto and Toby were able to show definitively, and more convincingly, that this was a heat activated channel.”

Makoto Tominaga, an electrophysiologist, was already an assistant professor in Japan when he joined the Julius lab in San Francisco to learn molecular cloning. While Caterina had been working to discover new ion channels, Tominaga had been building an instrument for patch clamp electrophysiological recording, often called a rig, that would let the lab listen in on electrical impulses from individual channels (see “How to tell if a channel is open”), which he used to confirm that TRPV1 opened a cation channel in response to capsaicin.

The lab suspected, based on noisy preliminary data and on knowing that TRPV1 governed a response to pain, that the channel might also open in response to heat.

The experiments were difficult to perform. Adding heat introduced problems with the microscope: It changed the volume of liquids, including the oil between the microscope lens and the sample, causing cells to heave out of focus. Temperature-induced shifts in position also sometimes broke the fine stretched-glass electrodes that Tominaga used to isolate a single patch of membrane. In addition, before fluorescent proteins were widely available, it was hard to tell which cells had been transfected, so he had to work through many cells to find the few that responded to capsaicin.

As with the calcium imaging, the difficult experiments paid off in the end. Tominaga found that heating a cell would open the channel, letting cations flow into the cell.

“The most exciting time in my life was when I saw the heat-evoked activation of the ion channel,” Tominaga said. At the time, he added, “there was no such concept” as a channel opened by temperature. “I was really, really surprised and really excited to see that.”

He wasn’t alone in his excitement. Rosen said, “Once we saw the heat data, it became clear, like holy cow, this is why hot peppers are hot.”

Having shown that changing temperatures could open the channel, the lab wanted to learn more about how it detected shifting temperature, whether the cation influx was fast or slow, changing stepwise or all at once as the media heated up. But the cell heating equipment they used relied on what Rosen called a “toaster oven–type technology.” It tended to switch on and off, oscillating through a range of a few degrees instead of maintaining one temperature — which made it very difficult to be certain what, precisely, the channel was responding to.

Rosen was the only undergraduate Julius had ever hired. As the youngest and least experienced member of a lab full of postdocs, he found that their jargon-dense molecular discussions sometimes went over his head.

“After four years at Berkeley, I could just barely understand these guys,” he said. But having worked as a sound engineer at concerts throughout high school and college, he was by far the lab member most comfortable with building complex electrical systems.

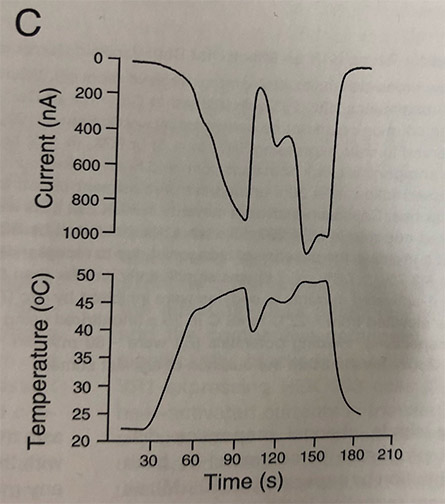

Using parts he ordered from an electronics catalog, Rosen developed a device that could control and record the temperature of the cell media with much greater precision. Using it, he showed that in frog eggs expressing many TRPV1 channels, increasing the temperature gave a stronger cation current; decreasing the temperature did the reverse.

One memorable assay, which Caterina playfully called the “wiggle–waggle experiment,” showed just how temperature-sensitive the channel was. When Rosen warmed a frog oocyte expressing TRPV1 past 43 degrees Celsius, he saw a quick increase in current as the many channels in the oocyte’s membrane shifted from closed to open. When he turned the heat back down to just below the threshold, the channels closed, and the current ceased. Up, down: The ion flow, which reflected the behavior of many TRPV1 channels added together, increased dramatically above a characteristic temperature and dropped off below that temperature. Within a range near the threshold, where many ion channels opened or closed at once, the current and temperature graphs formed mirror images.

“Even the small reduction of temperature caused a huge reduction of current,” Tominaga said. “This experiment clearly suggests this channel has a thermospecific threshold for activation.”

As it happened, that threshold temperature was also very close to the temperature at which humans begin to feel heat as painful. But the threshold was not fixed immutably. TRPV1, the lab found, can respond to numerous stimuli, often in an additive way. For example, acidity can lower its opening temperature, suggesting a partial explanation for why damaged tissue can feel pain at normally harmless temperatures.

David McKemy, who joined the lab as a postdoc a few years after TRPV1 was found, recalled that after presenting on the lab’s investigation into TRPV1 heat sensing, Julius often was asked, “What about cold?”

After all, temperature sensing is not binary. If we can feel other temperatures, did that hint at other TRPs?

How to tell if a channel is open

The TRP and Piezo channels recognized in this year’s Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine have something in common: They are cation channels that, when open, allow positively charged ions such as sodium and calcium to cross the plasma membrane.

This works because neurons maintain an ion imbalance that gives them an overall negative charge compared to the external environment. As a result, when a TRP or Piezo channel opens, sodium and calcium flow into the cell, reducing the negative charge, or polarization. Strong enough depolarization may start an action potential, which enables one neuron to communicate with another.

The studies that led to this year’s prize used two methods to determine whether these channels were open.

Calcium imaging: Because mammalian cells keep calcium concentration very, very low compared to the outside of the cell, a spike in intracellular calcium is a sure sign that a calcium channel has opened. Researchers can use indicators that fluoresce when bound to calcium to check for influx through channels in the plasma membrane or release of calcium stores from the endoplasmic reticulum. Calcium imaging was the approach that Caterina and McKemy used to narrow a huge list of candidates to the individual genes involved in capsaicin and menthol sensing.

Oocyte whole-cell electrophysiology: To detect depolarization, an experimentalist uses an extraordinarily fine electrode, usually made from a stretched glass micropipette, to poke through a cell membrane and then record the voltage inside the cell compared to the extracellular fluid. This technique is useful for determining how a cell’s voltage (or ion concentration) is responding to stimuli.

Patch clamp electrophysiology: A wider pipette than the oocyte whole-cell recording electrode, still usually made of stretched glass, is used to suction into a cell’s membrane, separating one section of the membrane from the rest. The researcher can pause here to record from the whole cell or proceed to remove the separated patch of membrane and detect individual channel opening events as tiny changes in current. This technique is useful for isolating one or a very few channels and seeing how they respond to stimuli.

The Secret History of Touch Series

Michael Caterina and the capsaicin receptor

How the Julius lab found that an ion channel senses heat

Makoto Tominaga, Toby Rosen and TRPV1 heat sensation

Nobelist’s postdoc searches for a receptor for mint and cold

Patapoutian’s postdoc unearths the powerful Piezo gene

Bertrand Coste and the pressure receptor

Nobelist’s lab pins down pressure sensing in mice

Seung Hyun Woo, Sanjeev Ranade and Piezo2 in the sense of touch

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition monthly and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

How a gene spurs tooth development

University of Iowa researchers find a clue in a rare genetic disorder’s missing chromosome.

New class of antimicrobials discovered in soil bacteria

Scientists have mined Streptomyces for antibiotics for nearly a century, but the newly identified umbrella toxin escaped notice.

New study finds potential targets at chromosome ends for degenerative disease prevention

UC Santa Cruz inventors of nanopore sequencing hail innovative use of their revolutionary genetic-reading technique.

From the journals: JLR

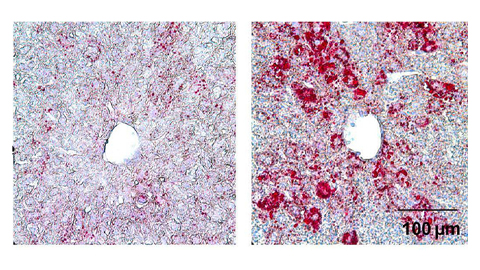

How lipogenesis works in liver steatosis. Removing protein aggregates from stressed cells. Linking plasma lipid profiles to cardiovascular health. Read about recent papers on these topics.

Small protein plays a big role in viral battles

Nef, an HIV accessory protein, manipulates protein expression in extracellular vesicles, leading to improved understanding of HIV-1 pathogenesis.

Genetics studies have a diversity problem that researchers struggle to fix

Researchers in South Carolina are trying to build a DNA database to better understand how genetics affects health risks. But they’re struggling to recruit enough Black participants.