Overcoming missed connections to battle Alzheimer’s

A recent study revealed that a protein important for neuron communication is associated with patient resistance to Alzheimer’s disease and may delay cognitive decline.

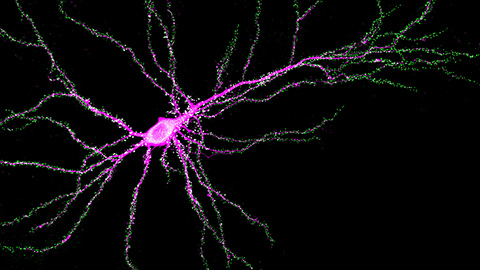

Like the cord that connects a telephone handset and the receiver, a neuron needs to make a physical connection with other neurons to communicate and transmit signals, which allow people to think and speak. The new study published in the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics suggests a protein, called neuritin, may allow some people to retain their neuronal connections even when toxic substances that cause Alzheimer’s attempt to break them down.

Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of dementia and affects more than 5.8 million Americans. To diagnose it, physicians use mental competency tests, physical and neurological exams, brain imaging, spinal fluid tests and medical history. Most patients show both a cognitive decline as well as toxic protein accumulation in the brain, which causes neuron death and brain shrinkage. These abnormal protein aggregates, called amyloid beta plaques and tau tangles, can disrupt neuronal connections and communication, which leads to memory loss and confusion, the hallmark symptoms of Alzheimer’s.

However, some patients show characteristic signs of Alzheimer’s pathology in their brains when examined but remain mentally competent. These individuals are known as “cognitively resilient” by the researchers who conducted the study.

“How cognitively normal older individuals with Alzheimer’s disease pathology withstand dementia onset is one of the most pivotal, unanswered questions in the field,” said Jeremy Herskowitz, associate professor of neurology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine and co-supervisor of the project.

To tackle this question, Herskowitz and Nicholas Seyfried, a professor of biochemistry at Emory University School of Medicine and co-supervisor of the project, teamed up and combined their specialties in proteomics and basic neurology to examine proteins in human brain tissues.

Unlike widely employed hypothesis-driven research, this team studies diseased humans and their tissues first to discover potential therapeutics.

“That's quite different than traditional approaches, which try to make discoveries in experimental model systems,” Herskowitz said. “Our research collectively identifies differences in humans first. Then, after that discovery is made, we can ask questions in experimental model systems to work out what's going on at the molecular and cellular level.”

The researchers conducted a large mass spectrometry screen of the proteins found in the brains of healthy people, typical Alzheimer’s patients and cognitively resilient patients. Cheyenne Hurst, a graduate student at Emory and co-lead author on the study, used high-powered computer programming to determine that neuritin correlates with intact cognitive function over time.

“The higher the amount of neuritin you have in your brain, the more likely you are to be cognitively intact,” Hurst said.

The researchers then wanted to test how the protein affects how neurons communicate. To do this, they isolated neurons from the hippocampus of rats and treated them with either neuritin, the pathogenic amyloid beta or both.

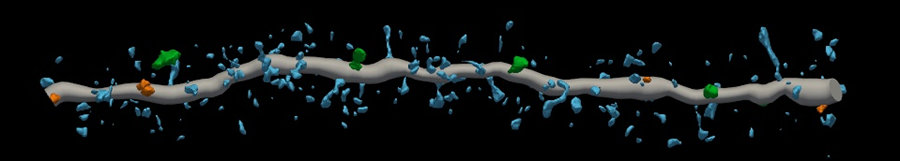

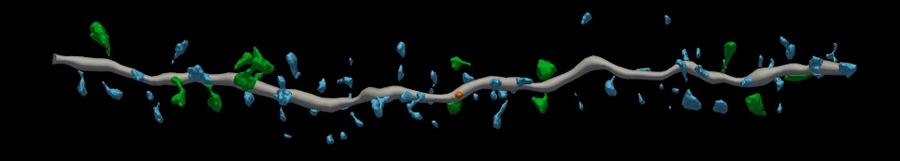

Derian Pugh, a graduate student at UAB and co-lead author, noticed structural differences in the three groups.

“The dendritic spines or synapses coming off healthy neurons kind of remind me of branches on a tree,” Pugh said.

But the structure of the neurons exposed to pathogenic amyloid beta was disrupted — and so were their connections with other neurons. Pugh said they “looked like a tree with no branches.”

However, neuritin completely blocked the detrimental effects of amyloid beta on the neuron cultures.

“With these experiments, we were able to recapitulate what happens in humans that display cognitive resilience and a possible mechanism,” Herskowitz said.

The team plans to focus on the basic biology of neuritin but also on how they can harness neuritin as a biomarker of Alzheimer’s or a therapeutic.

“The ability to estimate the amount of amyloid beta pathology in an older person's brain using biomarkers is getting very advanced,” Seyfried said. “We can predict quite accurately the presence of amyloid beta is in someone's brain while they're still alive. If they have a large amount of amyloid beta, but they're still cognitively normal, they may want to one day get treated with neuritin or drugs that boost neuritin levels so that those symptoms don't develop into dementia.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition monthly and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Genetics studies have a diversity problem that researchers struggle to fix

Researchers in South Carolina are trying to build a DNA database to better understand how genetics affects health risks. But they’re struggling to recruit enough Black participants.

Scientists identify new function of learning and memory gene common to all mammalian brain cells

Findings in mice may steer search for therapies to treat brain developmental disorders in children with SYNGAP1 gene mutations.

From the journals: JBC

Biased agonism of an immune receptor. A profile of missense mutations. Cartilage affects tissue aging. Read about these recent papers.

Cows offer clues to treat human infertility

Decoding the bovine reproductive cycle may help increase the success of human IVF treatments.

Immune cells can adapt to invading pathogens

A team of bioengineers studies how T cells decide whether to fight now or prepare for the next battle.

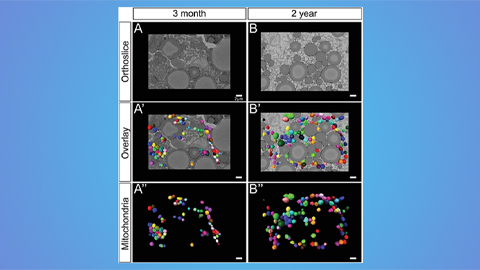

Hinton lab maps structure of mitochondria at different life stages

An international team determines the differences in the 3D morphology of mitochondria and cristae, their inner membrane folds, in brown adipose tissue.