Do sperm offer the uterus a secret handshake?

Why does it take 200 million sperm to fertilize a single egg?

One reason: When sperm arrive in the uterus, they are bombarded by the immune system. Perhaps, molecular anthropologist Pascal Gagneux says, many are needed so some will survive. On the other hand, the female may benefit by culling so many sperm.

“I’m a lonely zoologist in a medical school,” Gagneux said. “My elevator spiel is that all of life is one big compromise. (For an egg), being too easy to fertilize is bad; being too difficult to fertilize is also bad.”

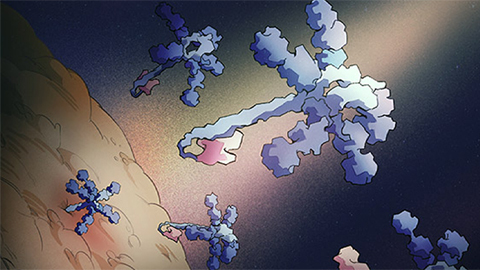

Gagneux’s lab at the University of California, San Diego, has discovered the makings of something that might be compared to a secret handshake between sperm and the cells lining the uterus in mice and, perhaps, humans. Uterine cells, they report in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, express a receptor that recognizes a glycan molecule on the surface of sperm cells. This interaction might adjust the female’s immune response and help sperm make it through the leukocytic reaction.

.jpg)

The leukocytic reaction is not well understood. What we do know, Gagneux said, is that “after crossing the cervix, millions of sperm — a U.S. population worth of sperm — that arrive in the uterus are faced by a barrage of macrophages and neutrophils.”

This attack by the innate immune system kills most of the sperm cells in semen, winnowing hundreds of millions down to just a few hundred that enter the fallopian tubes. The defensive response may help prevent polyspermy, when an egg is fertilized by more than one sperm and cannot develop.

Sperm are coated in sialic acid–rich glycans, and the innate immune system uses sialic acid to differentiate human cells from invaders, so Gagneux and his lab expected that the glycan might interact with innate immune cells called neutrophils. But human neutrophils they tested were activated to a similar degree by sperm with and without sialic acid.

Meanwhile, the team noticed sialic acid–binding receptors called siglecs on endometrial cells. In solution, these endometrial receptors can bind to whole sperm. According to Gagneux, the binding interaction might help the sperm run the gantlet of the leukocytic response — for example, by dampening the immune response. Alternatively, it may be a way for uterine cells to weed out faulty sperm. In the immune system, siglecs help cells to recognize sialic acid molecules as markers of the body’s own cells, and in that context they can turn inflammation either up or down.

“It’s somewhat embarrassing how little we can say about what this (interaction) means,” Gagneux said. To understand its physiological significance, researchers first must look for direct interaction between sperm and intact uterine tissue — this paper looked at only sperm interacting with purified proteins and isolated cells.

It’s humbling to work in such a poorly understood area, Gagneux said. Reproduction “is a very, very delicate tug-of-war at many levels. The fact that there is (also) this immune game going on is completely fascinating.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition monthly and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

How a gene spurs tooth development

University of Iowa researchers find a clue in a rare genetic disorder’s missing chromosome.

New class of antimicrobials discovered in soil bacteria

Scientists have mined Streptomyces for antibiotics for nearly a century, but the newly identified umbrella toxin escaped notice.

New study finds potential targets at chromosome ends for degenerative disease prevention

UC Santa Cruz inventors of nanopore sequencing hail innovative use of their revolutionary genetic-reading technique.

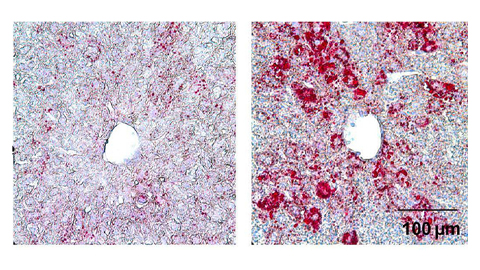

From the journals: JLR

How lipogenesis works in liver steatosis. Removing protein aggregates from stressed cells. Linking plasma lipid profiles to cardiovascular health. Read about recent papers on these topics.

Small protein plays a big role in viral battles

Nef, an HIV accessory protein, manipulates protein expression in extracellular vesicles, leading to improved understanding of HIV-1 pathogenesis.

Genetics studies have a diversity problem that researchers struggle to fix

Researchers in South Carolina are trying to build a DNA database to better understand how genetics affects health risks. But they’re struggling to recruit enough Black participants.