JLR: A fatty liver drug? Not so fast

Sarah Spiegel knows a lot about sphingosine-1-phosphate, or S1P: She discovered the molecule in the 1990s. But she also knows there’s a lot still to learn. A study from Spiegel’s lab at Virginia Commonwealth University, published in the Journal of Lipid Research, highlights the complexities of signaling by this enigmatic lipid — and shows that targeting it may not fix fatty livers as easily as researchers had hoped.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, or NAFLD, the leading cause of liver transplants, is rampant among people who consume a high-fat diet. The disorder starts when excess lipids build up in liver cells and eventually causes inflammation that does lasting harm to the organ. S1P is higher in the livers of people and mice with the disease. Given that link and the known role of S1P in inflammatory signaling, researchers hoped that blocking S1P signaling might slow NAFLD progression.

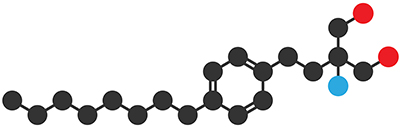

And there’s a drug that does exactly that. The prodrug FTY720/fingolimod, which is used to treat multiple sclerosis, is a sphingosine analogue that is phosphorylated in the body to an S1P mimic. In MS, it is thought to work by blocking S1P receptors on the surface of immune cells that otherwise would attack healthy tissues. Two years ago, researchers at the Mayo Clinic suggested that the drug could also reduce the symptoms of diet-induced fatty liver disease in mice.

“Nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases have a component of inflammation,” Spiegel said. “And FTY720 was known to be immunosuppressive.”

So the results of that first study made sense. But the dose used in the mice was quite high compared with the final plasma concentration of the drug in human patients. So, with postdoctoral fellow Timothy Rohrbach in charge, Spiegel’s lab tested the drug orally at about a third of the dose, a better match for treatment in the clinic.

The finding held up, but not for the reasons they had expected. In mice fed a fatty diet and sugar water, the researchers observed, treatment with FTY720 reduced lipid accumulation and liver size. But it didn’t do much to reduce the cytokine and chemokine signaling that are thought to push a fatty liver toward cirrhosis.

“We were surprised that inflammation was not the major component” of the drug’s effect, Spiegel said. “Yes, there were some effects on inflammation. But … the effect was mainly through suppressed lipid accumulation.”

In other words, the drug affected the first step in the disease, lipid buildup, without much changing inflammatory signals that usually result from that buildup.

By investigating lipid synthesis enzymes with a known connection to NAFLD in the treated mice, the team observed that fatty acid synthase was reduced while other enzymes did not seem to be affected. Of all the enzymes that make lipids, why fatty acid synthase alone?

Though FTY720 is expected to work through S1P receptors, Spiegel said, it may, like the sphingosine it mimics, have many targets. Her lab has shown previously that S1P can work in the nucleus as well. In this paper, they found preliminary evidence that the treated mice may regulate fatty acid synthase levels through histone modification.

“It’s a hypothesis at this point,” Spiegel said. “But I think it’s an intriguing connection. … In science, so many times you have a hypothesis, and the results take you to a different angle.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.