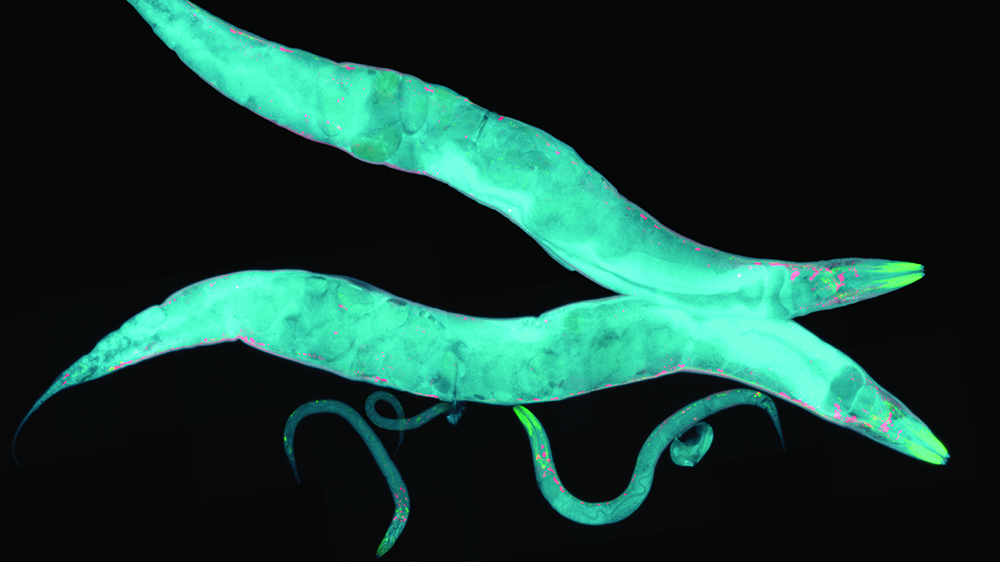

MCP: Worms, too, slow down

in old age

In efforts to stave off death, unicellular and multicellular organisms constantly are recycling proteins, breaking down those that are damaged to provide building blocks for fresh copies that can carry out cellular functions. The process is an uphill battle with an inevitable end: The recycling and refreshing slow down, causing cellular damage to continue accruing until the organism dies and ultimately is broken into biochemical materials for other life. This progression, known as senescence, occurs in nearly every organism on Earth and has been studied extensively in the model organism Caenorhabditis elegans.

The roundworms’ decrease in protein turnover doesn’t occur evenly, however. Researchers at Ghent University in Belgium recently determined that two families of proteins involved in intracellular movement and reproduction are especially hard-hit in the worms.

“It’s not a uniform slowdown of the whole set of proteins,” said Ineke Dhondt, a postdoctoral researcher in the university’s Laboratory for Aging Physiology and Molecular Evolution. Dhondt and colleagues at the Pacific Northwestern National Laboratory in Washington recently described their findings in the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. Previous papers in the field had determined that protein turnover in C. elegans decreases with age but hadn’t examined how significantly the effects varied between different families of proteins. “There are proteins that keep or retain their turnover,” Dhondt said. “That might be quite a different insight from other studies that only focus on the bulk protein turnover.”

C. elegans are widely used to study aging due to their short lifespan and well-characterized genomes. To examine which proteins were being turned over, the researchers fed subpopulations of the worms alternating samples of the bacteria Escherichia coli grown with either heavy or light nitrogen isotopes, characterizing the worms’ protein production with mass spectrometry before and after each meal over several days. The difference in isotope weights causes a slight weight difference in proteins that are subsequently synthesized, which can yield information about changes in protein production when compared with the previous spectrometer readings.

Dhondt and her colleagues found that the worms were decreasing their turnover of proteins in the tubulin and vitellogenin families, which are involved in cytoskeletal movement and production of eggs, respectively. They also found that ribosomal proteins, which are responsible for protein synthesis and all generally have a similar half-life, ended up varying widely in their turnover rates.

“We saw that these protein-turnover values really fan out over time,” Dhondt said. “That was an indication that this group might be important to dysregulation of the protein synthesis phenomenon, and that actually can be a key component to underlie aging.”

They also found that proteins responsible for protein degradation, such as the ubiquitin system, tended to continue their turnover throughout aging. “It’s like (the worms) want to keep up their function, so by refreshing these proteins, they want to make sure that these proteins keep functioning,” Dhondt said. “But in the end they’re fighting a battle that they can’t win, because the whole proteome will ultimately collapse.”

Dhondt and colleagues plan to continue studying aging in roundworms, with a new focus on the quality of health the worms exhibit into old age. “An important parameter for us is to look at the ability of the worms to move,” she said. “We are checking not only if the worms are living longer from a certain treatment but whether they are also exhibiting better health.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Cracking cancer’s code through functional connections

A machine learning–derived protein cofunction network is transforming how scientists understand and uncover relationships between proteins in cancer.

Gaze into the proteomics crystal ball

The 15th International Symposium on Proteomics in the Life Sciences symposium will be held August 17–21 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

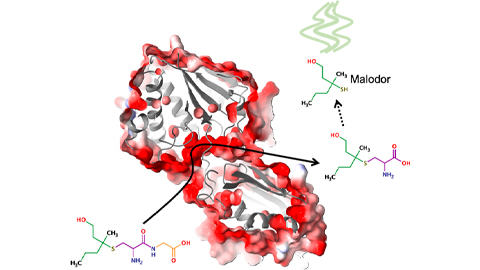

Bacterial enzyme catalyzes body odor compound formation

Researchers identify a skin-resident Staphylococcus hominis dipeptidase involved in creating sulfur-containing secretions. Read more about this recent Journal of Biological Chemistry paper.

Neurobiology of stress and substance use

MOSAIC scholar and proud Latino, Bryan Cruz of Scripps Research Institute studies the neurochemical origins of PTSD-related alcohol use using a multidisciplinary approach.

Pesticide disrupts neuronal potentiation

New research reveals how deltamethrin may disrupt brain development by altering the protein cargo of brain-derived extracellular vesicles. Read more about this recent Molecular & Cellular Proteomics article.

A look into the rice glycoproteome

Researchers mapped posttranslational modifications in Oryza sativa, revealing hundreds of alterations tied to key plant processes. Read more about this recent Molecular & Cellular Proteomics paper.