What’s in your dimer?

The term “homodimer” — shorthand for “sequence homodimer” — connotes a protein molecule composed of two monomers with identical primary structures. It often is assumed these proteins function as pairs of independently operating monomers, but there are other scenarios. Many homodimers show a substrate or cofactor binding with high affinity to only half of the seemingly available sites and behave as conformational heterodimers. This permits allosteric regulation that is not possible with true conformational homodimers.

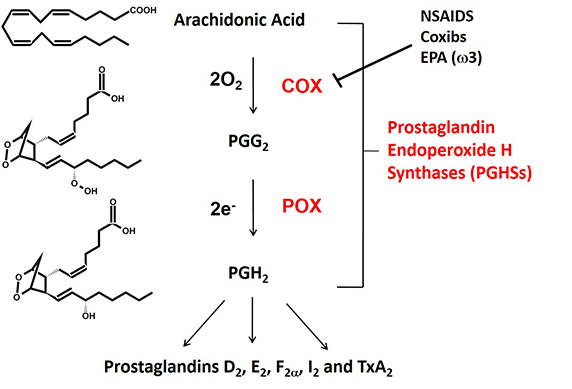

Fig. 1. The cyclooxygenase (COX) and peroxidase (POX) reactions catalyzed by prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases (PGHSs). There are two isoforms that are commonly known as cyclooxygenases-1 and -2 (COX-1 and COX-2).

Fig. 1. The cyclooxygenase (COX) and peroxidase (POX) reactions catalyzed by prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases (PGHSs). There are two isoforms that are commonly known as cyclooxygenases-1 and -2 (COX-1 and COX-2).

Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases are homodimers that function as conformational heterodimers. These enzymes, commonly known as cyclooxygenases, or COXs for short, catalyze the committed step in prostaglandin synthesis — the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostoglandin H2 (Fig. 1). There is a constitutive COX-1 and an inducible COX-2. These enzymes are composed of catalytic (Ecat) and allosteric (Eallo) monomers (Fig. 2). With COX-2 at least, Ecat and Eallo each remain fixed in the same form during the biologic lifetime of the dimer. Ecat binds heme more avidly than Eallo, and as originally observed by Richard J. Kulmacz and coworkers, maximal COX activity requires only one heme per dimer (See Kulmacz, R.J. & Lands, W. E. and Dong, L., et al).

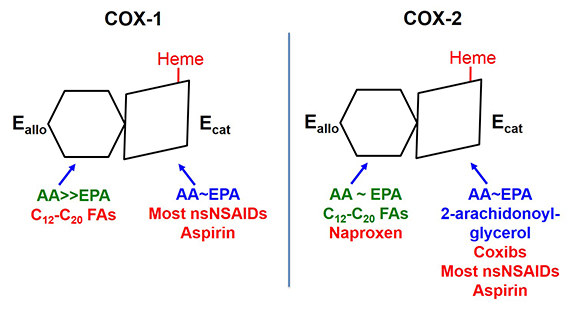

COXs are regulated by fatty acid tone — the cellular composition and concentration of free fatty acids. Different free fatty acids bind with different affinities to Ecat and Eallo (See Dong, L., et al and Kundalkar, S. N., et al). Free fatty acids binding to Eallo regulates the catalytic efficiency of Ecat. In general, the most common free fatty acids including palmitate and stearate and oleate inhibit COX-1. In contrast, palmitate is relatively specific for stimulating COX-2. Overall, high ratios of common free fatty acids to arachidonic acid, and low concentrations of arachidonic acid, activate COX-2 while suppressing COX-1. COX-1 and COX-2 are also differently affected by the omega-3 fish oil free fatty acids. For example, eicosapentaenoic acid inhibits COX-1 but not COX-2. The molecular basis for the differences in these free fatty acids effects remain to be resolved.

The two COX isoforms are sequence homodimers that function as conformational heterodimers. Both enzymes appear as structurally symmetric homodimers in crystal structures but function in solution as conformational heterodimers composed of an allosteric (Eallo) and a catalytic (Ecat) subunit. The subunits of COX-1 and COX-2 differ in their affinities for ligands and in their responses to ligands. Substrates are in blue. Ligands shown in green stimulate COX activity, and those shown in red inhibit activity

The two COX isoforms are sequence homodimers that function as conformational heterodimers. Both enzymes appear as structurally symmetric homodimers in crystal structures but function in solution as conformational heterodimers composed of an allosteric (Eallo) and a catalytic (Ecat) subunit. The subunits of COX-1 and COX-2 differ in their affinities for ligands and in their responses to ligands. Substrates are in blue. Ligands shown in green stimulate COX activity, and those shown in red inhibit activity

Interest in COXs as drug targets highlights their importance. For example, low-dose aspirin targets platelet COX-1 (See Patrono, C., et al and Grosser, T., et al). Aspirin, naproxen (ALEVE®), and ibuprofen (Motrin®) are mixed COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors called nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which relieve pain by targeting COX-2. Celecoxib (Celebrex®) is a coxib – an NSAID more specific for COX-2. Mechanistically, most NSAIDs and coxibs bind more tightly to Ecat than Eallo. Naproxen is unusual in being a direct competitive inhibitor of COX-1, but an allosteric inhibitor of COX-2 (See Dong, L., et al and Duggan, K. C., et al). As a consequence, naproxen can inhibit 100 percent of COX-1 activity but only 70 percent of COX-2 activity. This may explain why naproxen has limited adverse cardiovascular side effects compared with other COX inhibitors.

There is much more to be learned about these COXs including identification of likely dietary influences on these enzymes. Additionally, differences in cellular fatty acid tone may well contribute to adverse effects of COX inhibitors, thereby impacting therapies. Understanding the structure, chemistry and regulation of these enzymes remains an exciting area of investigation.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Missing lipid shrinks heart and lowers exercise capacity

Researchers uncovered the essential role of PLAAT1 in maintaining heart cardiolipin, mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, linking this enzyme to exercise capacity and potential cardiovascular disease pathways.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.