MCP: When prions are personal

Almost everyone produces the prion protein known as PrP, which is found in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid. Like most proteins, PrP folds into a characteristic structure when it is produced. But sometimes that structure can change. When one copy of PrP adopts a misfolded shape, other prion proteins it comes into contact with tend to adopt the same shape. The misfolded proteins spread like an infection, and they tend to clump together, damaging the brain.

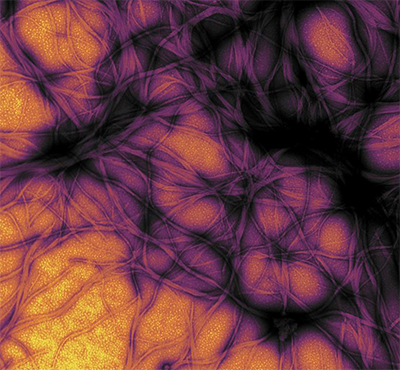

The prion protein forms fibrils like the ones shown here.NIAID

The prion protein forms fibrils like the ones shown here.NIAID

A research team with an especially personal stake in prion diseases has developed a new measurement that may be useful in testing the treatments they aim to pioneer.

For husband and wife team Sonia Vallabh and Eric Vallabh Minikel, prions became personal when Vallabh’s mother died in her early fifties of a mysterious, rapidly advancing neurodegenerative disease. An autopsy showed that the culprit was a genetic prion disorder, a variant in PrP that makes the protein more likely to adopt a misfolded prion conformation. A test revealed that Vallabh, who is now in her thirties, had the gene too.

“She has a very high probability of developing the same disease by midlife,” Minikel said. “And once it strikes, it’s rapidly fatal.”

After that genetic test, Vallabh and Minikel changed their lives. They started taking night classes in biology and took entry-level jobs in laboratories. They founded the Prion Alliance, a nonprofit dedicated to finding a cure. With support from leaders at Boston’s Broad Institute, they enrolled in Harvard Medical School, and last spring they defended their Ph.D. theses, which focused on the mechanisms of prion disease, in back-to-back seminars. Now they’re looking ahead toward testing treatments.

Researchers hope that if they can find a way to reduce the amount of prion protein in a person predisposed to prion disease, they can reduce the chances that person will develop the disease, or they might be able to delay the onset of symptoms.

But how will researchers know if a potential treatment is working?

“The first and most basic thing you do in a clinical trial that’s the first in humans is you try to find a dose that is potent and tolerated,” Minikel said.

To measure a drug candidate’s potency, researchers usually test for how much it affects its target. In this case, that would mean looking for a drop in PrP after treatment. However, in the normal course of this disease, the amount of detectable PrP drops dramatically after a person begins to show symptoms.

“It’s very nonintuitive … trying to lower a thing that already goes down at the onset of disease,” Minikel said.

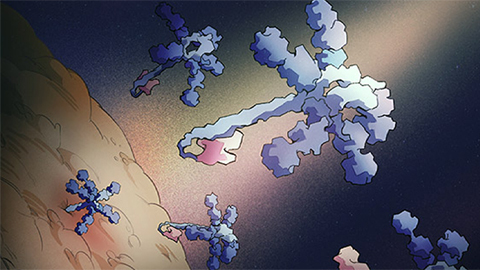

If disease progression and an effective drug candidate had the same effect on circulating PrP level, researchers would need to test the drug long before the disease began. And they weren’t even sure if the PrP drop in the test results reflected reality. The most common test relies on an interaction between PrP and an antibody that recognizes its shape. As PrP refolds, the researchers wondered, could it become invisible to the antibody while still present in the cerebrospinal fluid?

As part of his thesis work, Minikel helped develop a new test to resolve this question. With colleagues at the Broad Institute who specialize in proteomics, he came up with a way to detect PrP that doesn’t depend on the protein’s shape. Instead, using a mass spectrometry technique called multiple reaction monitoring, the approach breaks the protein into bits and measures its constituent parts. That means that even if the protein has changed shape, the assay can still detect it. The work recently was published in the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics.

Using this new assay to measure biobanked samples from patients, Minikel and his colleagues confirmed that PrP in the cerebrospinal fluid drops in the course of prion disease. Where the PrP goes is still an open question. But with greater confidence that it is indeed dropping when disease starts, the team has a roadmap for the best possible clinical tests for the drugs that they’re starting to develop: They need to test potential drugs in people at risk of prion diseases who have not yet shown symptoms.

Working with a commercial partner, Vallabh and Minikel have started testing drug candidates in mice using antisense oligonucleotides, a technology that should suppress the production of prion protein. They hope it will reduce the damage done by misfolded PrP. The early trials give Minikel hope, he said: Mice with genetic prion disorders, if treated before they show symptoms, survive longer without disease.

Even if this drug candidate doesn’t prove effective, Minikel looks with pride at the groundwork they’ve laid.

“We’ve made tremendous progress in making this a what people in the industry would call a ‘developable disease,’” he said. “And I think that’s a really promising step forward no matter what happens with the antisense oligonucleotides.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition monthly and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

New class of antimicrobials discovered in soil bacteria

Scientists have mined Streptomyces for antibiotics for nearly a century, but the newly identified umbrella toxin escaped notice.

New study finds potential targets at chromosome ends for degenerative disease prevention

UC Santa Cruz inventors of nanopore sequencing hail innovative use of their revolutionary genetic-reading technique.

From the journals: JLR

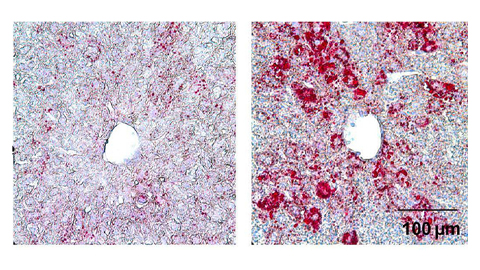

How lipogenesis works in liver steatosis. Removing protein aggregates from stressed cells. Linking plasma lipid profiles to cardiovascular health. Read about recent papers on these topics.

Small protein plays a big role in viral battles

Nef, an HIV accessory protein, manipulates protein expression in extracellular vesicles, leading to improved understanding of HIV-1 pathogenesis.

Genetics studies have a diversity problem that researchers struggle to fix

Researchers in South Carolina are trying to build a DNA database to better understand how genetics affects health risks. But they’re struggling to recruit enough Black participants.

Scientists identify new function of learning and memory gene common to all mammalian brain cells

Findings in mice may steer search for therapies to treat brain developmental disorders in children with SYNGAP1 gene mutations.